The smell of São Paulo is thick. I arrived an early Wednesday morning and a two-hour Uber ride took me from the airport to my room in the center. My body was sweating in continental confusion as my wide eyes was trying to take in the city. I stared at the concrete highrises with their specific pichação ‘graffiti’, the helicopters transporting the rich far over traffic jams, the homeless resting on pieces of cardboard, the trees of an endless variety of species and colorful queers dotted in the crowded avenues. São Paulo is the biggest city outside of Asia and with a metropolitan area of over 22 million people and the world’s largest pride parade this is a city buzzing at its’ own frequency, and it’s a hot one. The international theatre festival Mostra Internacional de Teatro de São Paulo or MITsp had already been going on for a week and I was in town to see as much as I could of the remaining five days.

MITsp is an international theatre, dance and performance festival that takes place annually in São Paulo. It’s 9th edition in the year 2024 ‘remains faithful to its’ experimental and critical vocation’ with a varied program from performances to workshops to critical discussions and lectures. Notable also is the fact that the 2024 edition only curated works and artists from the global south, i.e Asia, Africa, Southwest Asia and Latin America.

In two articles I will write you through the seven performances I saw. I write you through a family’s grieving songs, dance as spiritual practice, trans-atlantic exchange of trans-femininity, clinical poetics of the favela and crip centric erotics. Throughout the two texts I will brief, analyze but most of all pose questions. As a visitor and stranger to the city, the country, the culture, the people, and the language there are few things I can write with certainty. However, the continuous state of being lost in translation is a brilliant place to ask questions from. Let’s start from the very end.

A Shocking Sentence

The very last thing I saw at the festival was an intimate concert by the Argentinian trans singer, actress, activist, and writer Susy Shock. She performed at Centro Cultural São Paulo, an incredible venue that seamlessly weaves together public and private space. So as when you’re in some audience seats you can see and hear out to the people practicing break, vogue, tango or tik-tok dances in the outdoor areas of the center. Nevertheless, Susy demanded all attention. With a stage-presence reminiscent of a grand storyteller she worked through many of her emotionally charged songs totally acapella or accompanied by a small drum. In between her politically charged songs she told stories in Portunhol, a pidgin language merging Spanish and Portuguese. Because Susy was putting in an extra effort to make herself understood I, with my childish Portuguese, could follow along. Between a song about male violence and toxic agriculture she said this sentence: “Nós não temos tiempo para metáforas” or “We don’t have time for metaphors”. As the words were uttered from her mouth and scribbled down in my notebook, the whole seven performances and my experience at MITsp became cohesive. This very sentence turned into a glue that aligned the performances and produced a series of questions these two articles hang out with. Primarily these questions are trying to probe how mediation of lived experience operates on stage, what it produces and how it is worked with as artistic material. Is all artistic material metaphorical? Is there a tangible difference in modality between working with lived experience and working with abstraction? What can speaking directly and with emotional conviction about one’s own lived experience on stage produce? What are the processes of translation enabling the mediation of, and potential empathy with, lived experiences? How can artistic practice produce lived experience? In a Brazilian context, where socio-economic inequality is immense, how does professional performing arts play a role in the struggle against such injustices?

What is Brazilian dance?

The first piece I saw at the festival was Eu Não Sou Só Eu em Mim – Estado de natureza – Procedimento 1 (I am not only me in myself – State of nature – Procedure 1) by the Florianópolis based dance company Grupo Cena 11 choreographed by Alejandro Ahmed together with the 13 other performers. The program declares that the piece proposes an anarcho-choreographic counterpoint to the anthropologist Darcy Ribeiros’ (1922-1997) attempt of articulating a concept of ‘the Brazilian people’. Now, as a stranger, a foreigner, I know very little about this. However, in a conversation with my friend and São Paulo-native Marina Dubia I was told that there was an 20th century intellectual movement in Brazil that tried to define a national identity. Paulistano (‘from São Paulo’) intellectuals travelled the country in search of a unifying identity, an attempt that was doomed to fail in a country so ethnically and culturally diverse.

As I entered the proscenium there was a stone being carved by a machine. The sound it produced was looped into an electronic soundscape that really kicked off as the dancers entered the stage. The 14 dancers, wearing stylized gray training clothes, became a crowd as they engaged in a simple stepping-pattern choreography that slowly grew more complex. Moments of outburst appeared as single dancers broke out from the mold of the group simply to return. This tension between collectivity and individuality seemed to be at the heart of the piece as my attention was continuously shifting between macro and micro scale. This tension seems not only to refer to the choreography but also to the composition of the group, there were a variety of communities represented on stage. However, there was a dominant majority in the group consisting of young, white, and abled-bodied women. This majority made the individuals that didn’t belong to those communities stick out in a way that to me, felt posed and slightly awkward. Specifically, because this majority seemed to be full-time employees of the company and the other guests. Whilst still working primarily in the contemporary techniques of the company, which the hired dancers obviously were trained well in, the guest performers presence and differing skill sets didn’t feel artistically taken care of. It seemed to me their presence was to justify the theoretical pursuit of the piece, posing the question ‘what is a Brazilian dance?’

Here my cultural blind spots came into play. The cultural specificity of some movement material, the visual references (tropical forests, Gorey-selfies and ethnically diverse family portraits) of the loud AI-art being projected all over the stage flew by me, seemingly carrying larger contexts than I could fathom. However, the harsh aesthetic and rough physicality does make ‘anarchochoreographic’ a feasible term for a piece trying to give body to the question of how the immense cultural and demographic diversity makes a unifying national identity for Brazil impossible. The piece poetically employs vivid dancing, loud electronic music, and projected AI-visuals to lift questions like: ‘what does it mean to be Brazilian today?’, ‘What is a Brazilian dance?’ and ‘What are the processes that give body to national identity?’. Something I believe it is never trying to answer or produce, but rather Eu Não Sou Só Eu em Mim is entertaining the very inter-dependence and contingency that sharing a nation-station with such diverse demography entails. Which in turn defies the idea of a national identity as a unifying motion. Rather this is a work, where dance is attempting to give body to a sensibility of multiplicity.

Lost in Translation and Emotional Empathy in Portuguese

The next piece I saw was Lanca Cabocla by the group Platforma Lanca, performed by Abeju Rizzo, Inaê Moreira, Tieta Macau and guests. With a live soundscape by Runa Francisc. I entered a dimly light space with five circles of salt. In the circles were different objects: plants, pots, powders, vases, and candles. The three main performers and the sound designer are bare-chested engaging in a collective dance that flows in between the circles and up against the audience. The steps resembled a folk dance and even though I lacked the cultural references to read whatever they were performing, I could tell this space was sacred. There was a spiritual charge to their communal dance, the circles on the floor and the way they addressed us in the audience. From the text material to what I witnessed, I gathered that this performance was an iteration of, or at the very least inspired by, afro-brazilian spiritual tradition.

The pieced moved on through Fransisc’s rich soundscape, the three dancers kept moving in their hypnotizing communal patterns, blending leading and following as if was the most obvious thing in the world. Before the lights went out a few people from the audiences joined the dances and disappeared. It was first when they started singing that I paid more attention to the people around me. Joining the singing and thus revealing to me that she ‘gets it’, was my neighbor to my right. She was a black middle-aged woman that was watching the piece attentively, with her whole body. I decided to tune into her state, and actively watch the piece assisted by what I could gather from her experience. When the lights went out and the performers were crawling in between us with lit candles in their mouths, we both held our breath together. And when suddenly, one of the performers wrapped themselves up in fabric and wore a potted plant like a crown, we focused in together.

The same performer then embarked on a long monologue in portuguese, of which I understood nothing. But through the tone of the voice, I understood that this person was addressing political issues head on. My jaw dropped at the emotional conviction, and I was swept away with speculating about what exactly was being said. Until I noticed the woman on my right again, she was deep in tears. Her voice trembled as she began to reply ‘SALVE’ at the performers command. Salve literally means ‘to save’ but is used as a greeting and/or a statement of agreement. In Lanca Cabocla it seemed that the audience was agreeing to political statements made by the performer, the content of which I was clueless to. Suddenly, the whole room was chanting salve and I found myself tentatively joining the crowd, moved by the emotional intensity of it all. It was physical empathy, in action. I was again being tossed into similar questions: How is direct personal-political speech dealt with as artistic material? What are the aesthetics of this kind of speech? And how can performing arts serve it?

Whilst trying to dig deeper on what Cabocla means I stumbled upon the article: ’Caboclo Ritual Dance Bringing the Juke-Joint into the Church’ by Daniel Piper published in 2007 by ReVista, the Harvard review of Latin America. In it Piper describes the figure of the Caboclo, a sort of entertainer that mimics the image of a Caboclo spirit. Now, Caboclo refers to spirits that in afro-brazilian religious practice are images of indigenous peoples as well as it is a demographic term for a person with mixed indigenous and European heritage. For some spiritual practitioners it is a spirit that can possess people into extravagant sessions of song, dance, and buffoonery. Pipier describes it as such: “Through the caboclo’s body, spiritual power is not tactfully restrained, but dramatically exhibited—or perhaps generated—through athletic movements, astonishing endurance, speedy footwork, and spontaneous delivery of one song after another.” Looking back, Lanca Cabocla suddenly starts to make sense. Throughout the performance there seemed to be a continuous channeling of this spirit, read through a performative presence unfamiliar to me. As I clapped and whistled for the performers engaging in a collective hug, Pipers closing sentence comes to mind: ‘In the African Diaspora, modernity, dance, and spirituality seem to get along quite nicely. (…) certainly, it is possible to “get some religion at the Saturday night dance.” Certainly, it is also possible to get some religion at the performance festival. And even though I was more lost in translation than ever, tears falling down a cheek and the trembling of a touched voice told me enough to trace an understanding.

Mark my moves: Surveilled into Subjectivity

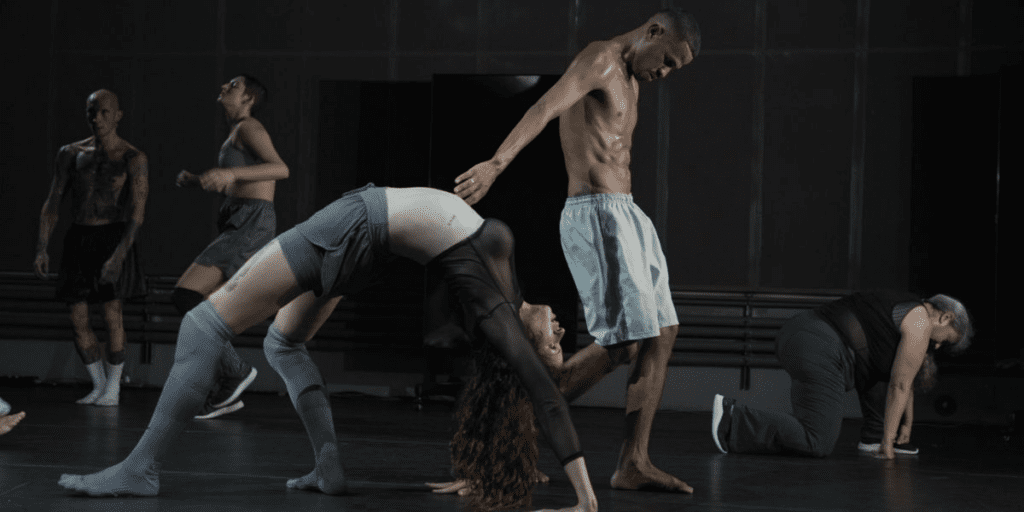

O Que Mancha (That which Stains) by Brazilian duo Eduardo Fukushima and Beatriz Sano was a 35-minute dance duet performed on a podium with audiences on both sides. The two dancers engaged in a long, continuous, and highly refined movement and vocal practice that both stunned and attracted me. They moved low, rolling on the floor and on their knees. They moved fast, chirping like birds while their fingers were flicking. They moved together and they moved alone. Immediately spectating this piece became sensorially complex yet never overwhelming. The work was filled with visual, aural, and social information and these 35 minutes passed by in an instance. With a sophisticated dramaturgy that never allowed me to leave but also didn’t force me to stay.

It was only half-way through the work, where they from all fours looked up at the ceiling to the sound of a drone, that I started to zoom out. There were people sitting on the other side of the room and due to the architecture, there were people watching from above as well as loud music of dancers practicing tango and vogue spilling into the space again. This could be perceived as a disturbance but to me, it amplified the central thesis of the piece: The stickiness of subjectivity by an imposition of surveillance and the practice of disappearing into unintelligibility.

In the book Capital is dead, is this something worse? McKenzie Wark proposes the term vectoralism as a new reigning economic system. She describes this new financial hegemony where it is no longer owning the means of production that produces a wealthy class, but rather it is the ownership of information and thus logistics. She calls it the information vector. Think Bezos owning Amazon and Musk owning PayPal. The obscene wealth of this so called vectoralist class, doesn’t come from the production of goods and services but rather from the ownership of marketplaces and systems of financial transfer: i.e, owning the logistics of capital. In vectoralist economies, surveillance is a common mechanism utilized to mine and sell the data of private civilians to optimize the efficiency of the vectoralists class logistical operations. The more you know about your customers, the more you can sell. In this political economy, being unintelligible, disappearing and confusing the algorithms is a subversive act.

The PR-text of O Que Mancha declared that the movement and vocal practice of the duo engages in a disruption of dualities. Where human and animal, man and woman, living and dead matter are challenged, diffused, undone. Through the refined choreography I did witness them becoming performative beings with other logics, teasing at the possibility of disappearing, by way of somatic fictions. The two dancers were hinting at the potential of confusing spectators to the point where subjecthood starts to be questioned. They were trying to exhaust the diffusion of their identities. But the eyes of the spectators across and above, the music spilling in and the fact that their names are plastered all over the program, reminds me of the contemporary impossibility to disappear. At least if you’re working as a freelance artist. But it left me with questions: How is identity produced by external gazes? Which gazes can read a person accurately, in accordance to their own self-perception? Is performed personhood ever accurate to the action one performs? What socio-economic forces determines the logics of subjecthood? Despite the impossibility to disappear I see the work as a well-articulated attempt at performing practices that do make it possible to vanish, if only for just a moment.

Resuming the Context: A Family Full of Tears

I rushed to see Ali Chahrours’ Told by my Mother without a ticket. At another SESC, one of many, many incredible culture centers of São Paulo, I managed to get in. The piece started with a long incantation, a mesmerising mantra-like text calling upon God. After this hypnosis the actress Hala Omran proceeded to introduce the piece and its’ context: On stage was Ali and members of his family: Hala Omran, Laila Chahrour, Abbas Al Mawla, Ali Hout and Abed Kobeissy. Together they told two harrowing stories of mother-son grief, and by extension love. I will write about one of the stories that concerned Fatmeh, Alis’ aunt, who lost her son Hassan in the early days of the Syrian civil war. With an emphasis on lost. Hassan was in Damascus in 2011 to renew some paperwork when the war broke out and has never been seen again. The performance begins with this story and so also with my tears. As the details of the story, and Fatmehs innumerable attempts of finding her son, were being told, I just cried. And I cried and cried and cried some more until I participated in the audiences’ choir of sniffles.

The story itself was heart-crushing in its’ emotional potency and the tangible grief felt by Fatmeh and the family at large. But what made it even more potent was how the piece was composed, performed, and choreographed. How the personal, explicit material was aestheticized and staged, centered and amplified the heart-ache of the story. There were songs, written by Fatmeh and Hassan themselves, played by Ali Hout and Abed Kobeissy sung together with Hala Omran throughout the piece. The songs were the motor of the piece and kept being played both separately and together with dances and movement scores performed by all cast members. From shaking on floor to rigid, rapid neck choreographies, the dances were of a rather simple nature but always performed with conviction and precision. The piece was truly a synergy between music, dance and narration, where the dramaturgy stood out as a captivating force. The timing kept the intimacy of the material vibrant and the emotional impact potent. All this without a notion of acting, of pretending, of make-belief.

The piece has become central to my questions springing from my experience at MITsp. Where is the line between a documentary and a performance? What is the difference between conveying an explicit message and performing an aesthetized translation? In the case of Told by my Mother what really made the piece both emotionally and politically piercing might just be the fact the choreographer was not necessarily doing this for the audience. In the after-talk Chahrour mentioned that the process of creating this piece was primarily for the family to heal and process their collective grief experienced by the loss of Hassan. The tangible personal importance of this healing process made the artistic material vibrate in a way that fiction rarely does.

In the artist talk Ali said that he works with “intimate stories that resume the context”. I quickly wrote it down in my notebook since I found the formulation peculiar. Resuming the context? What does that mean? It is not discussing or presenting the context, it’s resuming it. Has the context been paused? After pondering over Told by mother for almost four weeks now, I have an idea. By engaging with intimate stories heavily affected by conflict, the conflict, like Fatmeh and Hassan themselves, comes to life again. On stage, the story is being resumed. By talking about the continuous grief not only is the story not forgotten, but rather the immense love of this family and the Syrian civil war contextualizing that same love, continues, right there on stage. As an artistic, ritual, and discursive outpost in São Paulo. The context has been resumed, to be left as traces in the bodies of us, the spectators.

It’s conflicting to write and salute such a devastating work since it does truly resume the context. The whole Arab spring and the calamities that followed are packed into Fatmeh and Hassans story. One could even say that the Syrian Civil war is Fatmeh and Hassans story. The second-wave feminist slogan “the personal is political” comes to mind with such a pristine precision that I could not, not write it down. In Fatmeh and Hassans story lies a sliver of the emotional cost of this conflict. By bringing it to the stage Ali Chahrour manages not only to resume the context, but also to produce intense empathy with the processes of grief that (this) war produces.

This was the first part in this two-part article series. The next article will discuss the remaining three pieces I witnessed at MITsp, stay tuned.

Mostra Internacional de Teatro de São Paulo

Read more from Andreas Haglund