Ofelia Jarl Ortega (b. 1990) is a Chilean-Swedish choreographer and performer based in Stockholm. She has recently shown her latest work, Casino, at Dansehallerne in Copenhagen.

Casino is also what salsa dancing is called in Cuba.

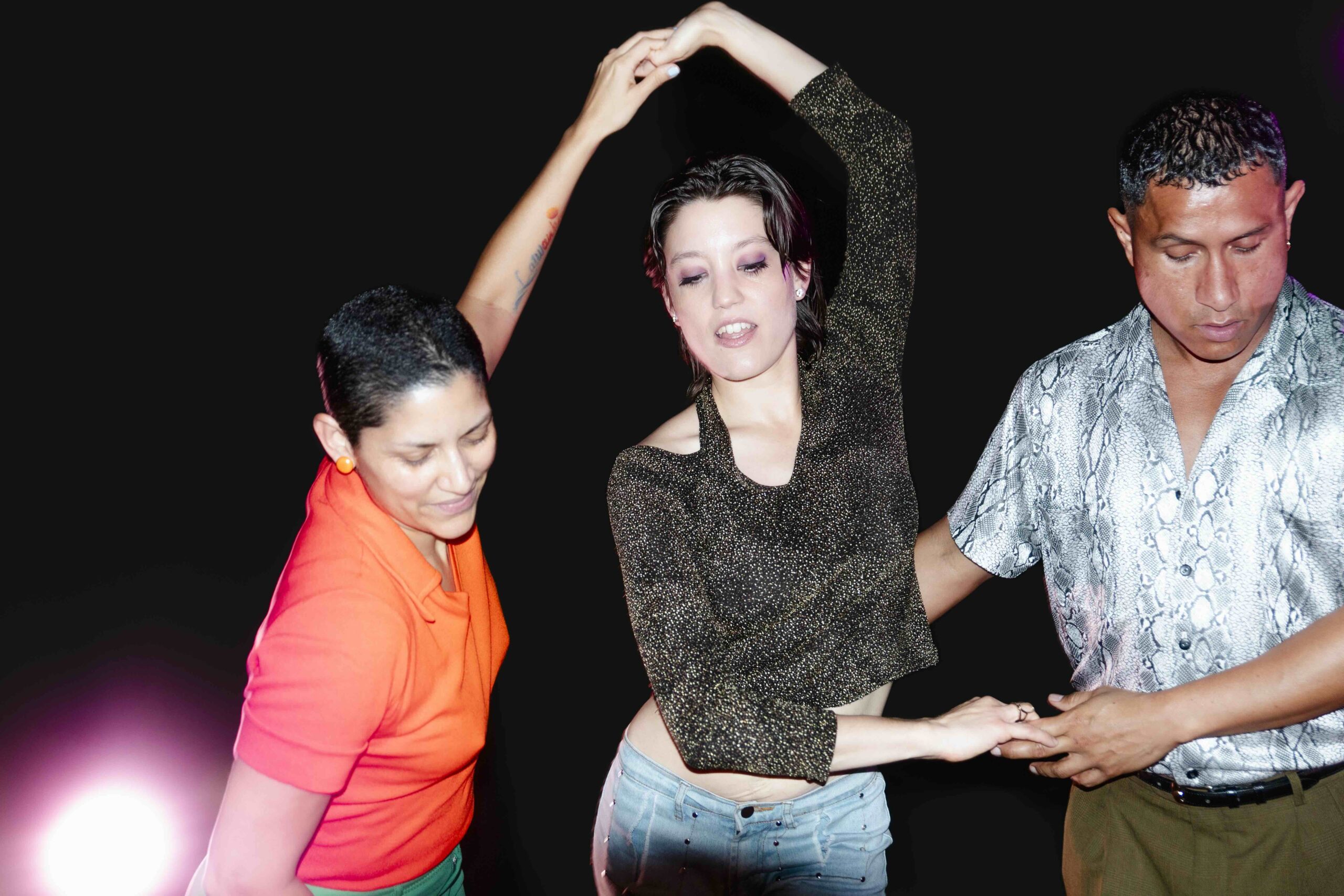

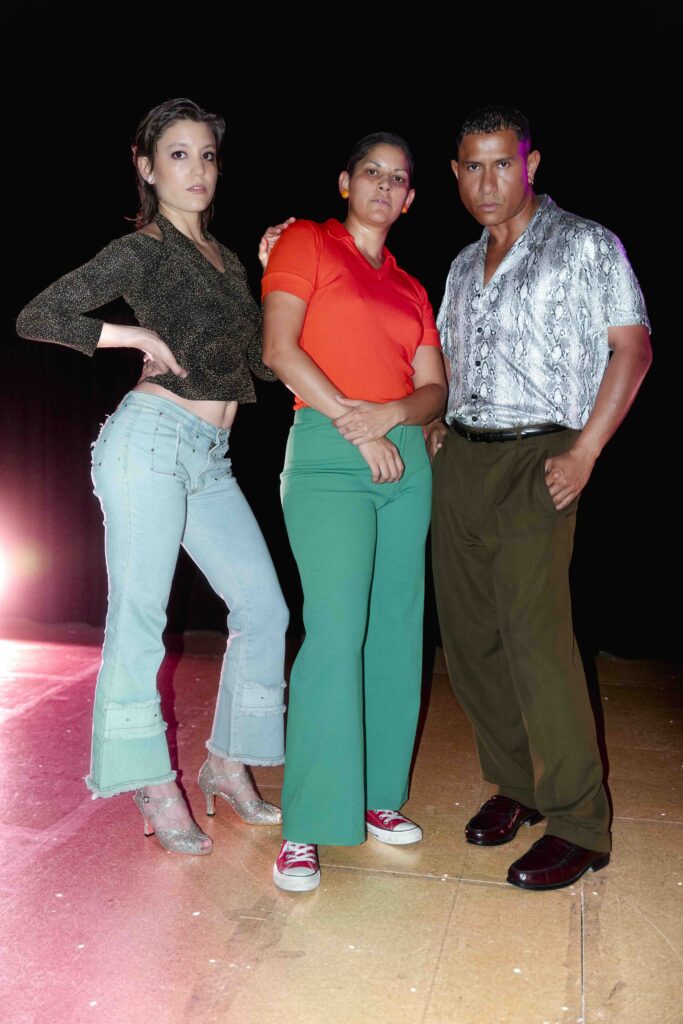

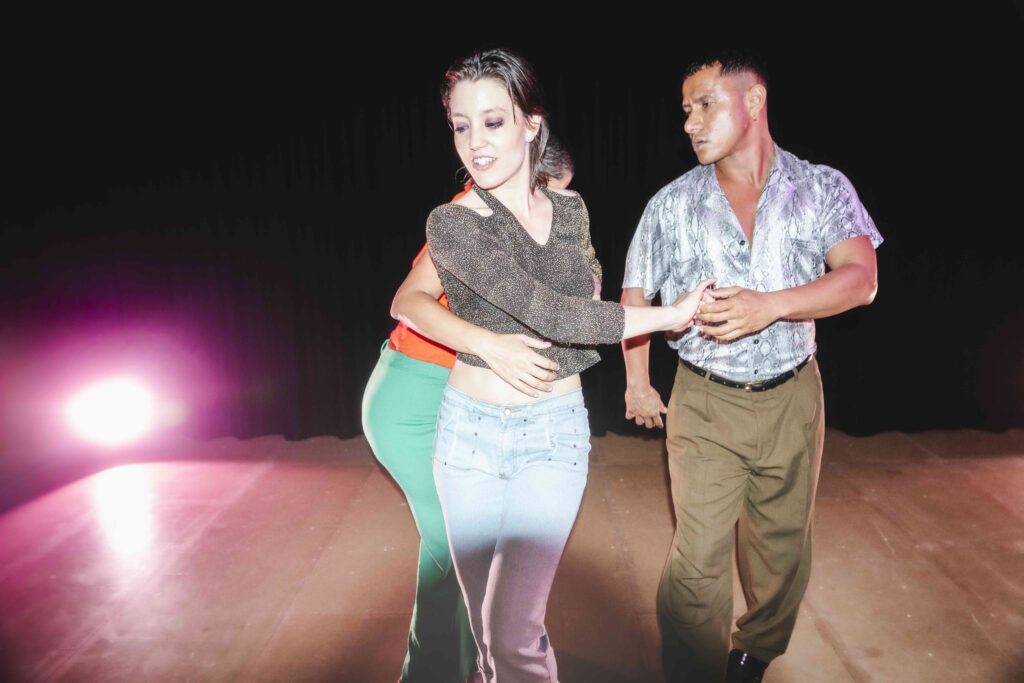

Together with the two other performers, Nina Sandino from Nicaragua and Jao Moon from Colombia, group dynamics and power relationships were explored through salsa. This came to fruition both within the history of salsa itself as well as within the group of performers.

When entering the black box at Dansehallerne, each of the performers had placed themselves in separate corners of the room. A 45 minute long performance began, where they each danced salsa, either with themselves or together. It was clear that the moves were in equal part deeply personal yet also from a tradition, emphasizing the performers as both individuals and part of a group and a legacy.

No music accompanied the dance, yet rhythm was felt through the sound of the feet on the floor and reverberated from the bodies. Occasionally, one of the performers would let a word slip out of their months, as if the sheer joy of the movements and the encounters with the other dancing bodies, could no longer be held in.

I left Casino feeling lighthearted and with a sense of an unusual performance, centered around joy and pleasure and with a deep curiosity to know more about Ofelia Jarl Ortega’s thinking around the work.

Karin Hald [KH]: What has the process been like creating Casino?

Ofelia Jarl Ortega [OJO]: The process for me in general has been like previous ones, where I try to get to know my colleagues as well as possible, their skills, desires and needs. I make myself open to the work, for it to inform me as well. From here, I try to find the specific movement vocabulary for each piece, based on the constellation of performers.

I had started the process by looking at my own desire to work with Latin American performers. Where does it come from, what does this ‘diaspora work’ mean to me? I assumed we knew different things around ‘diaspora’ and ‘Latin America’, and I wanted to place the work a bit further away from me, closer to them. Situated where they would know more than me, I’d need to expose myself and hopefully learn from the work as well as them. This learning process happens in all my processes, of course, but here it was a choice of placing the inquiry specifically in relation to Latin America, not just art in general. So, I was prepared to not know everything. And I was attentive to finding thevocabulary we would share. When we started to dance salsa during our first warm up, it was suddenly there.

KH: How did the hierarchies work in this regard; you were the initiator of the work and yet also learning from the dancers which you brought into the work?

OJO: I think it’s important to figure out the relationships on stage and while working. When it comes to power, there are certain positions that I can’t step down from, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. I’m the choreographer, I have the vetoes, but I make myself vulnerable and open to my colleagues and the work. I don’t call it a collective piece; I see it as my responsibility to lead the work. But I also acknowledge what my colleagues bring to the piece, their knowledge and skills. And they need to have the agency to activate the work in their own way.

When I first thought of this work, I knew that it was going to be challenging. To allow it to stay risky I chose to lower some other expectations. It was first called The Basement Piece, because I wanted to do something smaller, low budget, fewer co-producers, possible to present in any venue – or in a basement, somewhere. I wanted to follow my desire of getting closer to Latin America. I was afraid of what I was going to learn, that it, or even my desire, might be problematic or tricky. But I still needed to do it, and thus created the necessary circumstances to stay with whatever I would find. Then it slowly grew and in the end many people were interested, and perhaps that happened because it started small and I could stay true to my desire and not rush away to fulfil some (projected) expectations of someone. Even if that meant we had a small premiere in rural Sweden, with only 10 people in the audience.

KH: The placement of the work in a Nordic setting is crucial to the questions which lies at the essence of the work – how is it for you as a person with two backgrounds, Swedish and Chilean, to work in the Nordic Countries?

OJO: A question which came up in the process was: where can we tour this, does it only work in this form in Europe or especially the Nordic countries, or is it possible to present it in Chile, Colombia or Nicaragua?

It’s created in Sweden, because it´s where I grew up and always lived, but it’s talking with Latin America, the projection, or the dream, a place I never, but always lived.

I’ve been in conversation throughout the whole process with Latinos around me from different generations, about what it’s like to live in the diaspora. It has been very valuable, and a part of the research for Casino.

KH: The choice to have no music – how did that come about and what are your thoughts on this? For me, it made the work very intense and made me be able to focus even more on the movement of the dancers, the body was very heightened because I heard every sound the three of you made.

OJO: Music is very important in all my work, and rhythm especially. It’s almost like a collaboration between music and dance. The music becomes like scenography, that creates the world that we are in. In the works that are closer to silence, there has been an even bigger focus on rhythmicality in terms of phrasing, almost like the dance is sung with a melody or rhythm.

I could not imagine how I would write my own salsa music, and to use already existing music was no option. That would have been too charged with meaning, and steer the work away from where I wanted it to be, around and between the three performers on stage.

Salsa music is complex and rich, and great to dance to, and even so great that it’s also something which you can lean on. A companion to the dance, another partner or soloist. I wanted the dance to speak for itself.

KH: The work seemed to be filled with pleasure and joy, which to me is a very non-nordic approach to art and also just a way of expressing oneself – was this something that you were aware of in creating the work?

OJO: There was a lot of pleasure and joy in the process, even if that’s not what I wanted to convey with the work. However, I think this could be the effect, and sometimes the response from the audience, which is lovely. But it’s not where I start. I am interested in psychology and relationships, and especially friction, failure and pain. I am interested in solving questions that are difficult, together. Solving easy things on stage could be a metaphor for that. It’s tricky to dance without music – okay how do we solve this? How do we communicate? We danced, spoke and wrote together. It became about the joy perhaps because we didn’t start with trying to convey that, but rather the urgency behind coming together.

For me, it’s all about creating the possibility for the tricky things and negotiations to arise.

We talked a lot about ‘La sufrición’, translated as sufferment, instead of suffering. The word was generative for the process, and on stage.

‘La sufrición’ is for me this painful feeling when you’re left alone, or left with a suggestion that no one picked up, the struggle in the piece. It’s also linked to the painful desire of belonging (to a Latin American heritage, to the group on stage, to a salsa community…) In the work it became important to hold on to this painful feeling, to acknowledge its place in the piece and to look at it in a generative way, allow it to be there and also rest with it a bit.

To talk about hard things, I had to make it simple. And to make it simple you must go through the complexities, make them resonate in the simplest situation. I think I needed to be 34, have several years of experience, and even two kids, to make such a simple, yet complex, piece.

KH: The number of dancers was something which created a lot of the tension, that kept me hanging on – it was neither a solo nor a duo, with all the implications that come with each one of these frameworks, but three. The work seems to play with this – each dancer danced for themselves, with themselves as well as with each other and the audience.

OJO: All the parameters that the work has, also makes it break sometimes. The fact that we are three, the fact that there is no music, the fact that it’s not completely set, but that you can suggest a step which the others might, or might not, pick up on, makes it crash, eventually. You build, and build, and build, and then you have to start it all over again. It’s inherent in the choreographic structure that it will break.

If you are interested in relationships, it’s very gratifying to explore this in trios. But we also worked with a ghost. I have danced a lot of rueda. It’s salsa in a circle where you change partners constantly. I’ve danced this in a queer version, where being leader or follower isn’t determined by your gender, simply the placement you have in the circle. Uneven couples create ghosts, meaning if you don’t have anyone to dance with, you dance with the ghost.

Dancing with anyone despite gender, is of course not a thing in my work, but it could mean a lot to queers in a more traditional salsa world, where it’s sometimes expected to dance according to gender roles. In my turn it meant a lot to have these queer rueda gatherings to allow myself to continue with salsa in a queerer way on stage. I think the allowing feeling that came from breaking with gender expectations, could be translated into other ways of breaking with salsa expectations for me, on stage. Given that gender roles have never been a big thing in my work. So, the work lies in the intersection between traditions of queer expressions, salsa dance and contemporary dance. I have a foot in all these worlds, navigating between makes the work complex and painful, I think.

The ghost became a symbol of other haunted expectations, things that haunted us in the work, in ideas about what being latino is or what salsa is, or even what the music should be. In Casino we make space for all these things through the ghost as well. It’s a way to escape the feeling of being left out when the two other performers are coupling up. You could be alone, or you could go to the ghost, just as in rueda. In that sense we were actually or many people on stage.

KH: Did you decide together what the ghost looked like and where to find it on stage, did you build the same parameters?

OJO: The ghost was there from the beginning. And even more important in the beginning than later, since it gave us a framework, and was one of the early scores to explore, which helped us make mistakes and have a guide.

Where Nina and Jao say “coco”, I say “cuco”. We have different words for ghost, because our Spanish comes from different countries. When you speak of translation or different expectations, projections, images or background, the ghost is an example of La sufrición, that we don’t even speak the same language.

So, the ghost is practically about La sufrición, not wanting to be alone, about difference, and equally a metaphor about what’s haunting us.