I feel I should make an introduction to the British artist Rose English, but do you need to introduce an artist that have been an integral part of the European performance scene since the 1970s. Also, how to introduce 50 years of work in a few sentences without making her work something that it is not. Instead, I will let the title of this article serve as an introduction that both encompasses this interview and serves as clues to her praxis and bodies of work. The interview took place in Rose English’ studio on the island of Møn in Denmark.

The conversation begins with the garden. We are sitting in English’ studio looking out at the water of the lake Stege Nor and at the garden. After the interview we stroll through the garden taking a closer look at some of the flowers blossoming as it is May. The garden consists of small pathways going through beds growing with numerous plants looking both wild and controlled. We talk about gardening, about pruning apple trees, about control and letting go before turning to the reason I am there; Rose English more than 50 years praxis in performance art.

“I really like caring for a garden. Sometimes panic takes over and you keep cutting it down, but plants know how to grow, they have been doing it for millions of years, and they will find a way. The garden is a great teacher. “

My first question touches on the processes of archiving which seems an intrinsic part of Rose English’ praxis. The archive both as something physically preserving notes and objects and as something ephemeral that keeps the different ideas in the process sparkling for a future use. I ask her when this archive of hers began and when it occurred to her that archiving was important especially in performance art.

“The archive is part of the overarching thinking that precedes and comes out of the live event. I think it started because there is no fixed moment the performance begins even if the event or performance only happens once or at a particular time frame. For many artists a lot of work has gone before that moment and sometimes a lot of work happens after that moment. It is all part of ’the work’.

I was really interested in photography, so in the beginning I would approach or develop the performance through photographs that I took, but also objects that I made, scenarios that I would direct and set up almost like tableau vivant. I took photographs of this to inform my thinking about the event of the performance.

On the other side of the event of the performance we end up with the documentation. I felt this was important to me; some little spark or point of light which would lead back to the essence of what this event had been. There were of course artists who didn’t want a record and who viewed it as anathema as performance was about being in the moment, but I wanted both.

Those photographs particularly of the early proceedings and performances are works in their own right; I can go back to them and maybe they will lead to another performance in the future. Over the years my praxis has changed in terms of how to prepare for a performance.

Later my work became less object-led and more language-led. I was writing a lot, and it was important for me to keep workbooks, scripts, storyboards, or the score of the work before it had happened. There’s a vibrancy around those ideas when they are coming into being, and maybe didn’t find a place in the final performance. They can ignite a future work. “

It is not just new works and ideas the archive can sparkle, but revisiting old works can also create installations and exhibitions in the present; currently English has a big retrospective in Museum der Moderne Salzburg and this fall she will revisit older bodies of work at Rønnebæksholm and at Ringsted Galleriet.

“I have revisited some early performances and created installations around that body of work in the past decade; for instances Berlin from 1976 with Sally Potter at Heirloom last year. This autumn at Ringsted Galleriet I will be revisiting the performance called The Double Wedding from 1991 and pairing that with a collaborative film work that I had worked on called The Gold Diggers. The Gold Diggers is about the history of cinema and The Double Wedding is a meditation of the nature of the event itself. Some of the characters asks: “What is the double wedding?” And they all have different memories of it being a work in the past they were in. Both works are meditations on their own form even though they are from different decades and in different media.

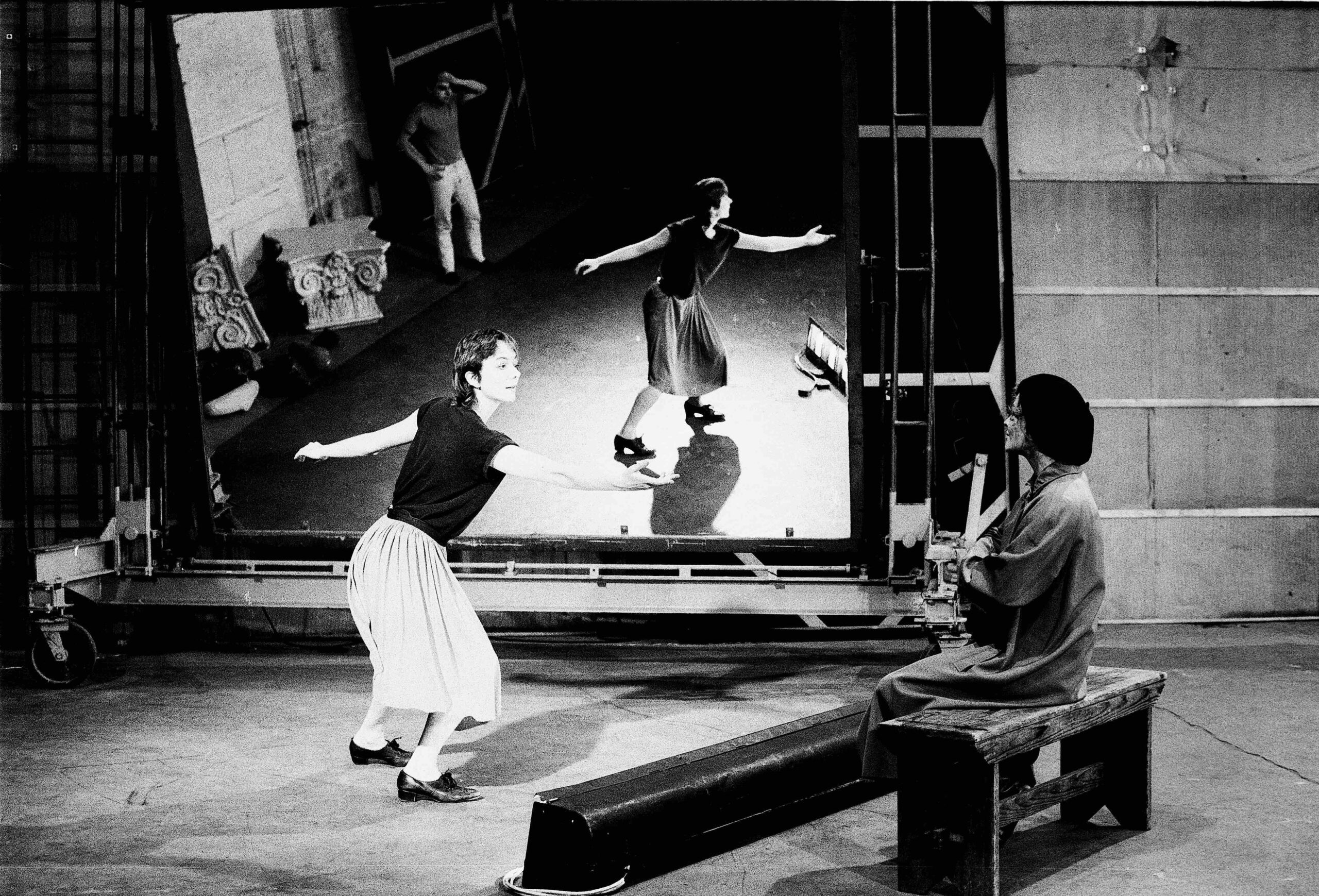

Rose English The Double Wedding (performance to camera 1), 1991 Photo: Hugo Glendinning. Courtesy: Rose English Studio

A film documentation of the performance from 1975 called Quadrille is part of the third section this fall of the yearlong program at Rønnebæksholm about the horse. It will just be the film, but I also created an installation now at Tate which includes the film. In 1974 before I made the performance Quadrille, I made an installation to explore the ideas. I made one pair of hoof shoes and one tail. I took photographs of myself wearing those objects and created an installation with those elements. Meanwhile I started to prepare the other five sets of shoes and tails for the following summer. So, Quadrille was an installation first, then it became the performance, and then it came back to be an installation.”

We shift from the archive to the stage, a word central in Rose English praxis, and also connected to space and to the arena. I ask her to elaborate on these words in relation to her praxis and how early the stage as a specific place comes into her preparations; a big question with different answers depending on which period or body of work in English’ praxis we talk about.

“Stage and space are very loaded for me. In terms of space, it is an interest in the notion of emptiness that space might give rise to and the sense of potential that may or may not be present in space as a result of it being empty. I associate the word stage within a theatrical tradition and of course theatrical space is a very potent place. The word arena surrounds both space and stage. Arena is an ancient and archaic word which predates the notion of the stage as the stage started to appear maybe in medieval times, and before, in terms of the western tradition of theatre, it was the arena; usually a natural amphitheater in the landscape.

I like evoking the arena on the stage and what it might be. I am interested in the conventions that were developed for the stage after the move away from the arena. The shift or the moment when it was necessary to bring what was happening in the space the arena was presenting to an audience inside, and to close the view the audience had been seeing and create this single scenery.

During the 1970s when I first started to make performances, they were very much led by an interest in the site specific, although we didn’t have a name for it then. It was about creating an event for a particular site whereby the context of that site would inform both the performance and how people would experience the performance as the audience would bring a sort of pre-knowledge or expectations. Quadrille was for example presented at a dressage competition and the audience was in some way involved with horses. So that performance had a particular interest in expectation, in lack of interest or even hostility as a result of who the audience were.

Then for a period of time, I explored site specific performance more deeply. The performance cycle Berlin that I made with Sally Potter was performed in the house we lived in, at an ice rink, a swimming pool and then returning to the house. It was very much about working in these very vibrant and different contexts and bringing the audience into a domestic space and then to spaces usually associated with sport and not with performance, theater, or exhibition.

Later I think, as a result of working with language I became increasingly interested in the idea of theatrical representation and I sought actively to make my work in buildings representing theaters. I had to develop a different body of knowledge about how to get access to, how to produce work for, and how to work with different collaborators to enable me to put shows on in those spaces. Along a thirty year’s period I became more interested in the conventional proscenium stage. I wanted to explore the particular language of theatrical representation, and over a period of about a decade I did three big shows on a proscenium stage.

Since it has been a different site of arena. I have made bodies of works that have been site specific again. They have also been music led in terms of collaborations with composers and object led like my early work but more about the phenomenology of different things being in juxtaposition of each other; for instances a body of work I made with Chinese acrobats, glass objects, and music.

The whole reason I started making performances was that it brought all the things I was interested in together in one work. It was not because I wanted to make performance art, which already very early on started to have a narrow definition of what it was and was not.”

From the stage we turn to the audience and our conversation returns where we began with the archive. Rose English’ first performances were image-led and without words. Then entered a monologue which evolved into a dialogue both with other performers on stage and the audience. English calls the act of being there as an audience a generous thing, but also something that in its own way creates an archive, if a more ephemeral one.

“There is a generous exchange between what happens on the stage and the audience. The people in the audience agreed to and are very generous to be there. Therefore, there is an expectation that something will occur which is very helpful when you are improvising, which I did in those early performances when I was speaking.

As a young artist it was really wonderful to find ways avoiding the work being too mediated by placing performances somewhere people would just come across. Nobody would explain what it was, and people would just have their direct response to it; maybe they weren’t interested or were thrilled.

I made a performance in the forest many years ago that people just going for a walk would come across. There was a sweetness of having that very direct relationship with the viewer or the public. I always feel that whatever took place is equally shared with whoever the audience is, and they carry a vestige or a trope of the event hopefully throughout their lives; they might not think about it, but it happened somewhere in their synapse. You can’t collate it, and you can’t build a database, but it is there. “