Under the Radar is New York City’s annual festival of experimental theatre and performance art. The 20th edition of the festival took place from the 4th – 19th of January 2025 across over 30 venues inhabited by 35 companies from all over the world. Filip Vest from bastard reports from the festival.

One of the first things that struck me with Under the Radar 2025 was the naturalness with which several of the venues managed and talked about accessibility. Coming from a Danish context where the topic is rarely addressed, and sometimes something as simple as having a wheelchair accessible venue seems a big hurdle, this serves as a reminder of just how natural accessibility can be integrated and with such a big impact. Emblematic for this was of course The Dan Daw Show, a show about disability and kink, that took place at Performance Space New York. The show was captioned, there was a day with an audio description and there was a model of the scenography that you could touch. Every performance was a so-called ‘relaxed performance’, where the audience could move around, come and leave at any time, and there was a ‘low-stim room’ available with minimal sensory stimulation. Integrated into the beginning of the performance, was also a segment where the main performer, Dan Daw, made the technician slowly turn up the music to the loudest point and the same with the most dramatic lightning changes that would happen during the show. He then informed us that a small icon in the captions would warn the audience before these dramatic changes in light or sound. In text this might sound like a lot of elements, but what was beautiful was how natural it felt in the space, how we were lead through all of it gently and not without humor by the brilliant performer-host, Dan Daw as well as the venue. Talking to the people working at Performance Space I got the impression, that they normally also have similar initiatives, but that they had cooperated with the Dan Daw group to implement even more, that will hopefully be integrated in future shows at the venue.

The show itself was not only a lesson in accessibility, but also a fun, hot, moving, personal story about sex, disabled bodies and non-disabled bodies. The audience is skillfully guided through the whole show by Dan Daw, in his own words “a crip in his power”. Together on the stage with him is ThomX, a performer without physical disabilities, so “you can also recognize yourself” as Dan Daw jokes to the able-bodied part of the audience. The two of them spend an hour and twenty minutes playing around with different kinky games of dominance and submission, while talking and lovingly joking with each other. Daw is instructed to do different things by his dominant performance partner, such as: getting undressed, walking around on all fours and being put into a sort of vacuum box contraption that wraps his body completely in skin-tight latex. “This is exactly how I want you to see me,” Daw tells the audience with a smile on his face. The Dan Daw Show plays around with the gaze and expectations of the audience: all the prejudice that exists towards sex and disability and of course the sheer lack of knowledge in the general discourse. The show feels a bit like spending time with a stranger, as if on a date, getting to know them and their intimate – and very relatable thoughts, like: “I wanna be in control and surprised at the same time. I’m such a messy bitch,” as Dan Daw says to the audience. In The Dan Daw Show submission becomes a way to reclaim a lack of agency: taking control over having your bodily autonomy taken away from you. Or as Dan Daw elegantly puts it near the end of the show: “When society fucks you deeply, make sure it does so with your consent…”

In stark contrast to the accessibility of The Dan Daw Show, the audience at 59E59E Theaters were told at the viewing of Old Cock, that we were absolutely not allowed to leave the theater during the play, and that going to the bathroom was not considered an emergency. I don’t know if it was supposed to be a joke, but either way it felt a bit awkward. Same goes for the monologue of Old Cock that was filled with not very interesting jokes and most of all felt like it didn’t have a lot at stake, even though the solo performer Jorge Andrade was doing a brave job trying to bring former Pulitzer-prize winning playwright Robert Schenkann’s toothless text to life. In the show Andrade is dressed as ‘the rooster of Barcelos’, a Portugese national symbol, and relates his own story, death and resurrection in this satirical play about authorities and myths. In the first part we get to know how the story of the rooster came to be and in the second part we experience the rooster in a video call with the deceased prime minister, António de Oliveira Salazar who ruled Portugal from 1932-1968 and was a dictator in practice. The rooster is infuriated about its instrumentalization as a ‘party favor’ and ‘cheap political trick’ in the hands of Salazar, but the dialogue between the two never comes to life and in the end it’s neither funny nor informing. Maybe the whole project is rather symptomatic for the conditions it was made under: a residency that the American playwright had in Portugal which gave birth to this short satire, but ended up merely as a fun postcard from a trip that never arrived at its destination.

Another bird character at the festival, that did win my heart though, was the dodo in the puppet show Dead as a Dodo by Wakka Wakka at Baruch Performing Arts Center, a play that I admittedly hadn’t booked a ticket for in the first place because I thought it was ‘just for kids’. In the play we follow two friends, a boy and a dodo, as they make their way across ‘the bone realm’ digging for bones to replace the boy’s missing limps all the while battling The Bone King and his mischievous daughter The Bone Princess. As the dead dodo starts coming back to life its existence becomes a threat to the bone realm and a hope for the realm of the living, a place a bit similar to our Earth in a maybe not so near future, where life is almost extinct. Such is the dark premise for this magical, morbid and melancholic play about the biodiversity crisis, death and existence. In Dead as a Dodo the heavy themes are not watered down for the children in the audience. The Norwegian puppetry company Wakka Wakka playfully makes these difficult subjects accessible while keeping them nuanced. Without spoiling the ending, I can say that we don’t get a happy ending per se, but maybe just a shimmer of hope. Throughout the 80 minutes of the play, I was either laughing, crying, dancing in my chair to the amazing songs or just sitting there with my mouth agape, blown away by the magic of the puppetry. I felt like I saw the show simultaneously as an adult and a kid. Afterwards I talked to my friend’s 10-year-old kid that also saw the play, and was luckily confirmed that this was not just one of those kids shows that the adults love, but also a perfect kids’ show for kids. There’s only one word that can sum up the experience of watching Dead as a Dodo and that’s: “Wow.”

Several more-than-human actors played important roles at the festival. In the show Cuckoo at Perelman Performing Arts Center, the story was told in by three singing rice cookers on stage together with a human performer. This lecture performance by South Korean artist Jaha Koo takes us through the past 20 years of South Korea’s history and challenged economy: the intense work culture, a symptomatic loneliness and the extreme suicide rate. Koo talks us through video clips and slides detailing the country’s financial crisis, IMF’s loan to South Korea, the so-called ‘national humiliation day’ and the musings of an American ‘happiness expert’. The research material is woven together with Koo’s personal story about a friend who took his life as well as interactions with and between the rice cookers and songs about “cooking rice until you die”. One of the rice cookers can talk and cook, one can talk and has a really nice LED-screen but can’t cook rice anymore and the last one, Quiet Hana, can only cook rice and say: “The rice is ready”. As the play evolves, the rice cookers go from being more of a comic relief to mirroring the tragic story of ‘a society under pressure’. “If I were you, I’d kill myself,” one rice cooker says to the one that can’t cook rice, in the beginning of the piece as a mean joke. By the end of the show this sentence has changed its meaning. Cuckoo has an elegant dramaturgy and uses its simple tools and metaphors in an impactful way. The piece has understandably toured the world and been shown more than 150 times.

The speculative research-based nature of Cuckoo feels related to another piece from the festival, The Search for Power at Invisible Dog Art Center that employs an almost detective-like approach to uncovering the mystery of the Lebanese electricity crisis. The live performance was completely booked, but I experienced the interactive audio version, where you go through a box of evidence collected by artist Tania El Khoury and scholar Ziad Abu-Rish, while listening to them narrating how they got the different material and what it all means. Through the work I learn how Lebanon has one of the worst electricity infrastructures in the world and citizens are still experiencing countless power outages today. The explanation is (of course) connected to colonialism. With their thorough and engaging research, the artists map the different political interests: the history of a French-owned electricity company, English modern imperialists, Belgian-owned infrastructure and how the United States always has its dirty fingers in everything. In short everyone wants a slice of the pie… Slowly a complicated history unfolds: secrets, bargains and strikes, illegal surveillance and powerful white men. The result is the completely dysfunctional infrastructure of the electricity grid in Lebanon today. The dense research material of The Search for Power is made easily accessible for the participant. You receive a pair of white gloves, a magnifying glass and some snacks, before you spend 45 minutes digging through a selection of the archive. The piece ends with a recollection of a dinner party that the artists had with friends in Lebanon: dancing in complete darkness during a power outage to the sound of Omar Souleyman’s remix of Björk’s Crystalline.

Power outages are also everyday material for Mariam, the main character in A Knock on the Roof at New York Theatre Workshop by Syrian/Palestinian playwright, actor and director, Khawla Ibraheem. We meet Mariam (performed by Ibraheem herself) living in Gaza during an unspecified time (but different clues point to the 2014 Gaza War). Mariam is living in a limbo, constantly expecting bombs to drop on her house. She’s waiting for ‘the knock on the roof’, the first small bomb that will serve as a ‘warning’, before more bombs will come (a technique used by IDF and others as some sort of sick idea of a more ‘ethical’ form of warfare, when you target civilian homes). Mariam knows she has five minutes to get out of the house with her kid, her mum and some stuff before the next bombs will fall. She starts training, setting alarms for her own fictional ‘knocks on the roof’ and tries how far away from the house she can get with ‘Pillowcase Nour’, a pillowcase filled with things with the same weight as Mariam’s son. It’s a brutal monologue, but the story is also told in a surprisingly humoristic tone. Mariam mocks herself for being an anxious mother, even though her anxiety is warranted. Slowly the disaster (terrifyingly) becomes everyday life, both for Mariam and the audience. At some point she almost hopes that the bombs would just drop now, so she could get over with it. Mariam is simply waiting and rehearsing for the disaster happening around her. Time is suspended or as she says: “Here in Gaza (…) Time feels endless, but none of it belongs to you.” Throughout the play, Mariam directly addresses the audience, asks them for advice on what to pack, exchanges running experiences and more in this chillingly logical reaction to war. Even when a group of audience members arrives late to the show, Ibraheem goes off script and jokingly sums the first scene up for them with the words “So… a war has just started.” The performance is equally relaxed and down to earth as the story is tense. A Knock on the Roof slowly draws you into its world of books, beaches and bombs living side by side, before leaving you with goosebumps in its chilling ending.

Where Mariam runs to rehearse her escape, in Iranian playwright and director Amir Reza Koohestani’s Blind Runner at St Ann’s Warehouse, running becomes a political statement in itself. We follow a husband visiting his wife, who is held captive as a political prisoner in Tehran. Through their conversation she convinces him to help a young blind woman with running. She lost her sight in a revolt and is now literally running blind as form of protest. Slowly the two start to form a bond before taking on the impossible and symbolic task of running through the 38-kilometer-long tunnel from France to the UK, quickly enough so they won’t be hit by the first scheduled train. In the program for Blind Runner I learn that the play is inspired by Niloofar Hamedi, an Iranian journalist who was imprisoned and used running in the prison yard as an act of protest. I can’t help thinking of Hamedi running around in his prison yard as one of the characters in Blind Runner utters the lines: “Running was the only thing that connected me to the exterior world”. The show was presented in Farsi with supertitles, and it felt very intimate spending an hour in the company of this beautiful foreign language, unravelling the story in a skillfully minimalist and underplayed format.

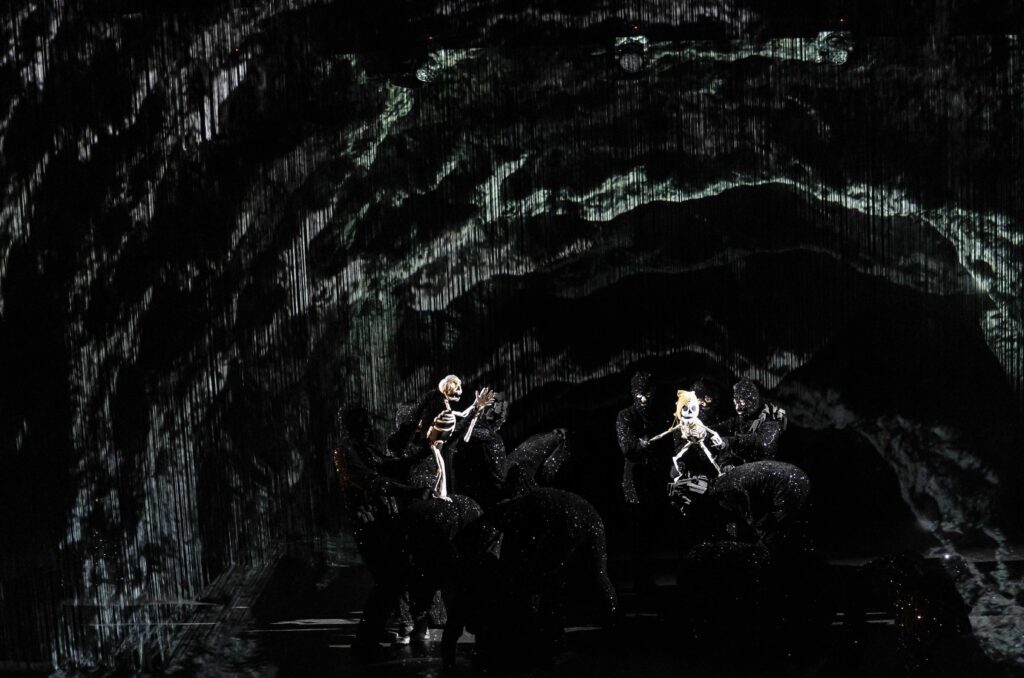

Generally, it was a happy surprise to see how many works were presented in other languages than English at UTR. Besides Cuckoo‘s Korean monologue and Blind Runner’s Persian language, Duke Bluebeard’s Castle was also presented in Japanese with supertitles at the Japan Society directed by Korean-Japanese experimental theater director Kim Suji. This experimental play from the 1970’s is the brainchild of Japanese cult director Shuji Terayama: a cabaret-like, Harajuku version of a French gothic horror story. We follow Bluebeard’s seventh wife trying to escape her deadly fate. It’s a dramatic, camp story with characters getting killed off in very creative ways, colorful drag costumes, baby dolls being thrown around on the stage and a ton of jokes about acting and theatre. Even though the premise and universe are wonderful, the whole meta-layer and intertextual references to Shakespeare and other playwrights feels a bit tiring in the end. But Duke Bluebeard’s Castle is for sure something different and an interesting piece of theatre history. It’s difficult to imagine just how wild it must have felt to experience Terayama’s underground plays in Japan in the 60’s and 70’s.

Another classic that was reworked at the festival, was the almost 100-years old musical classic Show Boat presented at NYU Skirball Center for the Performing Arts under the slightly changed title Show/Boat: A River. The original show has been equally praised for its prominent Black characters and songs as it has been condemned for its use of blackface and racial stereotypes. Its’ complicated history has made directors through the time try to work around problematic parts, and this version by Target Margin Theater was presented as a “daring reimagining … exploring America’s transformation from 1880s Jim Crow to the challenges of today.” In this version of Show Boat the casting is ‘colorblind’, there are only a small group of actors playing all of the roles, in turns wearing a sash to indicate if they’re playing a white character. But Show/Boat: A River can’t commit to its own concepts: later the sash becomes a medal before it completely disappears at a point where someone is clearly portraying a white character. I’m all for actors playing several roles, but in the end it simply becomes too confusing and stands in way of both the old story of Show Boat and the new they want to tell. At some point two actors play the same role at the same time, but the device is used so infrequently and idiosyncratic, that the point doesn’t really get through. Same with the blue x’s made with tape that adorned the back of several actors but isn’t used for anything. The music is the highlight of the show, and one of the more problematic original songs In Dahomey, where they sing in a made-up ‘exotic sounding’ language, is beautifully reimagined by the vocal arranger and co-musical director Dionnne McClain-Freeney: that flips the song and inserts a text of praise in Zulu. Overall Show/Boat: A River just feels indecisive in its creative decisions by director David Herskovits and most of all gives the impression of being one long workshop, that the audience must attend. By the end of the messy 2 hours and 30 minutes show, I can’t help thinking what it would have looked like with a Black director in charge: now that would have been a re-envisioning…

Under the Radar did in fact have a separate program for workshop shows (though Show Boat: A River was not one of them). The series Under Construction spotlights “works-in-progress from artists you should know.” Here I experienced a lot of works dealing with … work. A clown performance exploring the absurdity of work, a sing-along musical about emotional labor and an anti-capitalist ritual/rant. In Alex Tatarsky’s Nothing Doing we meet different melodramatic, manic characters caught between depression and fits of laughter, they navigate their own and societies’ holes, plots, bodies and boundaries. They’re caught in the middle of jokes, lost in the plot and struggling with the concept of working itself, or as a character jokes at some point near the end of the piece: “I’m struggling with the idea of a work in progress because it goes against my politics. I’m against work and I’m against progress.” (You can read my interview with Alex Tatarsky here). In another work in progress, Night Side Songs by the The Lazours and Taibi Magar, we meet Jasmine who gets a cancer diagnosis as she goes through different bureaucratical and emotional processes. The story takes the form of a sing-a-long musical, where the audience is invited to join the chorus for some of the songs. The show, that is based on conversations with nurses, doctors and caregivers is as much a story about the medical industry as it is a show about the nurses we are in each other’s lives. The simple chorus of one of the songs has been stuck with me since the show, when Jasmine’s partner sings to her: “I won’t know what to say. But I’ll check in on you … every day.” A song I think a lot of us, that are caregivers for someone close to us, will know. Finally, I also caught the work we come to collect: a flirtation, with capitalism by the artist collective the blackening presented at The Flea Theater, an absurd workshop performance of stand up and rituals, about not wanting to work but also wanting ‘to want to work’. The show seamlessly integrated ASL (American sign language) directly into the performance, as one of the performers was an interpreter, and interpreted their conversation while also being a character in the show.

And then we’re back where we started… Making accessibility accessible, in a completely natural and relaxed manner. UTR Festival 2025 presented an incredibly diverse program, both when it came to genres (that span from puppetry and clowning to lecture performance and sing-a-long musicals), but also countries, subjects and subjectivities. The festival was accessible both physically and metaphorically, opening complex worlds in playful manners. Besides being inspired by all the shows and different ways of working, overall, I’m just inspired by how diversity and accessibility is not a theme (or a hurdle) at Under the Radar, it’s just a condition for making work today.

Watch and learn, Danish art institutions and festivals…

Stuck in the middle of a joke we don’t know the ending of – Interview with Alex Tatarsky