There was a performance relay at Den Danske Scenekunst Skole/The Danish National School of Performing Arts on March 6-9, 2025, presenting the current five MFA students’ performances from their second semester. I watched three performances on March 6th and two on March 9th. The order of this review of the five works follows the schedule of the performances on both days. Since I participated in All these roads… as an outside eye, I had a better chance to talk, attend the rehearsals, and take a glimpse of the other works during their final rehearsals.

I wrote this review as a peer sitting next to the artists, while also trying to establish a connection between the audience and the works. Simultaneously, this peer review is written with the attitude of thinking together as a continuation of co-artmaking, aware that art performance is not created by an artist’s mastery, but by interaction with people all around, including the audience. Therefore, the artwork is not a completed product but an ongoing process with dialogues and reviews afterward. Experiencing the five performances with different styles and methodologies was a pleasure to taste each choreographer’s choreographic interests and professionalism. It also demonstrates the department’s capability to accommodate diverse aesthetics of dance performance art into their program.

The Place Where I Go to Listen

The four performers were dancing in color-coded costumes – the upper is navy, the lower is indigo – and had partially different pattern designs. Just as the color codes were shared, the four performers shared the choreographed movement phrase. Just like the costumes with various patterns showed slightly different individuality, it was possible to read that each performer was performing the spatial and temporal choreographic score with their own presence and interpretation. In other words, they all danced the exact movement phrase. Still, they slip slightly from the uniformity of unison due to their body movement texture, timing, and placement. One question came to mind. When does a group choreography become disciplined uniformity, and when does it not? If you remember the uniformity in classical ballet, modern dance, mass games, and the ignorance of individuality to achieve complete perfection, to what extent do regularity and irregularity disturb these classical, modern aesthetics of uniformity? What elements make unison irregular and reintroduce individuality?

As I watched this performance with these questions in mind, it began to resemble an ongoing experiment. The choreographic score seemed to be playing with purely abstract geometrical elements. As an audience member, I could clearly discern the shape and texture of the movement, the distance between performers, the repetition, and the differences in speed, timing, intensity, and light. These seemingly inhuman elements, however, prompted us to contemplate human social relations, the tension between structure and individuality, and the balance between rules and exceptions.

As the repetition of the movements accumulated and intensified, the performers’ state and energy were challenged, their exact movements were challenged, their eye contact with each other became distinct, and their individual characteristics with personal reactions to the score they were aroused. It was a very subtle and gradual way of seeing and feeling the performers. For me, this subtle relational individuality came up with the unexpected potential that cracks the structure. This ‘unexpected potential’ refers to the moments of individual expression that disrupt the structure of the performance, teaching me that the structuring process results in a structure. Thus, the structuring process is always ongoing in a structure, although it looks rigid from the outside.

The Script

Two performers stood on the stage, looking at a white A4 script. While listening to the sound of paper pieces turning or falling, audiences read the scripts in the performer’s hands as if looking askance at a stranger’s book who sat next. After all, the audience who sat surrounding the 4 sides of the stage read the text that something would happen to these two well-dressed people, and the performers started to move. One performer moved with a sense of volume, solidness, and heaviness intensified by her boots. Her precisely tailored asymmetrical jacket reconfirmed her character. The other performer moved like wind or feather-like lightness, wearing a wavy, romantic outfit with frills matching her movement textures.

The unfamiliar way of using movement lines in this work refreshed my eyes. It seemed like the two characters’ personalities were expressed not only through movements and costumes but also spatially. While one performer used diagonals and the corners of the stage, the other used the center line of the space. Afterward, when the two dancers met, the quality of their movements was mixed, and the spatiality of the two dancers was also mixed using the outline of the four sides of the stage, creating a rich terrain on the stage.

The allusion to the arrival of a fictional world in the beginning, the two characters’ secrecy, the lighting that creates cosmic space, and the alien-like voice flowing from the music invited the audience to project an imaginative world, a planet where only two beings exist. The mysterious atmosphere of this show made the universal story of two beings meeting and parting into a new story. When the two characters stumbled across each other by overlapping timing and unexpected contact, they unintentionally embraced, connected their arms, and moved across the space as if they were dancing a ballroom dance. The scenery of the couple dancing with connected arms, creating beautiful waves, was unforgettable. Since the title of this work is The Script, an unsettled, unspecified text, I interpreted the unforgettable scene by referencing other existing works and scripts.

I saw Angela Koh’s Total in Seoul in November 2024. The last scene in Total was like a mini solo version of the above scene, which also left a deep impression and was mimicked by the audience afterward. Koh wrapped her right hand on her stomach with her left hand. Her right thumb came up from the hug and made wave motions. I immediately thought of the alien parasite growing on her body by referencing Octavia Butler’s Blood Child (1995), a story about a parasitic relationship between humans and aliens, humans being protected by aliens but having to give birth to aliens’ children. Watching The Script inter-textualizing Total, which I inter-textualized from Blood Child, I think of a new, romantic, parasitic-symbiotic relationship where two human beings can be connected through a parasitic alien form (which links two human arms) and thus support a new relationship between the two. Breaking this relationship, in the end, one of the performers goes out and brings a printer on stage and continues to print the script. I couldn’t help but interpreting this behaviour as an homage to intertextuality and to the infinite imagination of fictions that continue to grow richer by referring to each other.

All These Roads Just for You

On the dark stage, the ambient sound of a car driving on the road was heard. At one point, one performer with a trench coat walked backward from the aisle next to the stage. As soon as the performer appeared, she started talking about Linda without a second pause. The performance description mentioned, “All the roads are in love with Linda. Linda has decided to stay home. Who are the roads and Linda?” The performer gave more detailed storytelling about how Linda had a good relationship with the roads. Even when Linda went to work only a 20-minute walk away, she drove on the road for 6 to 10 hours. When the performer humorously mentioned “the good old days and the promise of roads” – a hope and aspiration that humans could go everywhere – audiences may capture that sarcastic humour in the metaphor of anthropomorphic roads. While the absurd episodes of Linda and her neighbours, along with the eccentric storytelling, were introduced, laughter burst out from the audience seats.

The performer ends the story casually by saying that Linda decided to stay home. Then the lights brighten the stage. The narrator was no longer a storyteller but Linda on stage, and the stage became Linda’s home effortlessly. She started to move into her own space. The movements were minimalistic, such as rolling, walking, sitting, and gesturing. With that simplicity, we, as audiences, carefully focus on every movement to understand who this absurd protagonist is. Instead of offering a logical explanation of this character and the story’s background, this work invites audiences to add their own imagination upon creating Linda and her story, detecting the suggested signs and gestures.

Although the performance ended, I am still thinking about Linda, who decided to stay at home and no longer believes in the teleological promise of the roads, namely, human civilization. I am still thinking about how I can further develop this character, seemingly a passive one, but it is actively engaging in cultivating different modes of being, life, and worlds.

Antagonist

Three female performers and a doll-wearing wig were on the stage. The three performers wore costumes that highlighted the socially consumed sexual symbols of the female body, namely, breasts, buttocks, and pelvis. Performers were moving with an extraordinarily hyper and charismatic presence. The performers repeated highly tensioned and segmented movements and continued to show hyper-extended facial expressions. As the performers’ sexual appearance with their extreme physical state continued, the sexual symbols no longer contained sexual normality. In other words, the normality of sexual symbols can no longer be read within the boxes of femininity and femme fatale. They were transformed into monstrousness. Deleuze and Guattari said in Anti-Oedipus (1972) that the schizophrenic lives at the level of pure, unconstrained desire, and therefore, his experience has revolutionary potential. These schizophrenic, monstrous characters, who transcend the socialized norm of desire, indeed embody the potential to revolutionize the limited boundaries of femininity and sexuality.

It was interesting to reflect on ‘monstrosity’ through this work. Once, I questioned where all the invisible emotions and energies of those pushed away by society’s normality would go – the feeling of being oppressed, frustrated, and angry. Perhaps these invisible emotions and energies give rise to monsters. The monsters are the uncontrollable beings that warn society and the powers that profit from the status quo and standardization.

Real-time video recording and screening intervened during the performance. In the description, real-time video plays a role in questioning who the viewer is, who has the authority to pass judgments, and how shifting perspectives can transform power dynamics through changes in perspective. When this real-time video footage took over the stage’s back wall, it maximized the performers’ insane energy. It made the monstrous transformation even more spectacular. After that, the video moved on to filming each face of the audience. It was expected for a performance using real-time video on the stage. However, due to this work’s intentionally threatening and revealing character forming an uncomfortable relationship with the audience, when the audience’s faces were exposed on the back wall, we were suddenly pulled out of our speculation. It was a time when we were aware of our position and gaze, and may have felt a kind of shyness, shame, and rejection about our judgment.

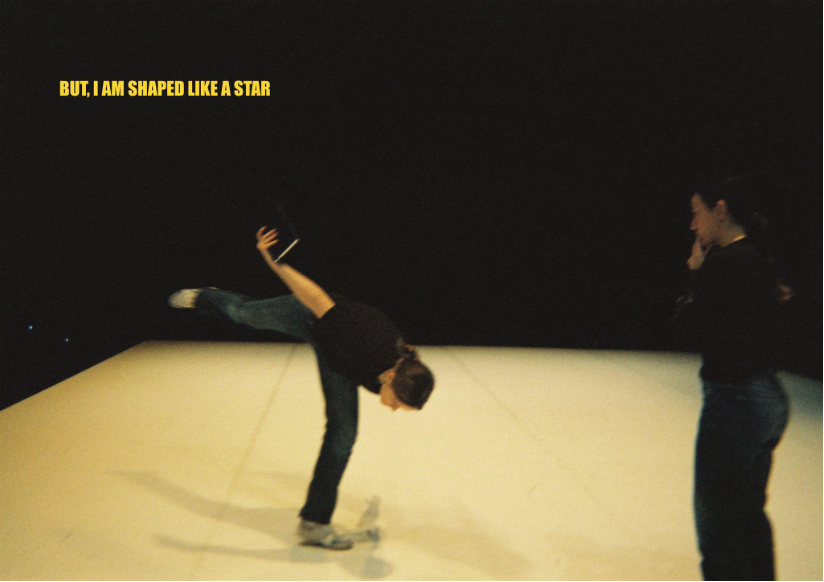

But, I am shaped like a star

One performer moved slowly and carefully on stage. As abstract movements and readable mimic gestures are blended, I experienced as if the performer were coming close to the audience, talking to them, and then keeping her distance from the audience. After that, one more performer appeared on stage, and the two started to dance as a duo. They danced with differing levels and movements but also aligned with each other in temporal unison. The duo also emphasized a strong and direct gesture, such as holding both hands to their chests. Later, the backstage opened, revealing the broad empty space behind, and a third dancer appeared dancing, heightening the atmosphere.

The contemporary dance movement techniques shared by these three dancers were clearly recognizable. At the same time, the intentionality and emotion of the movements were precise and appealing. In the contemporary dance performance context, following the philosophical turns of ‘phenomenality’ and ‘performativity’, expressions of emotion and storytelling movements have been perceived as ‘representative’ and old-fashioned. Although the intellectual criticism of ‘representation’ was toward the rigid certainty of logic-centered science and language, it became a criticism of ‘representative expressions’ in general in the performance field. The word ‘representation’ has been contaminated. Through this work, I came to reflect on this tendency. Perhaps in the present, the term ‘performativity’ is interpreted differently and used in a broad sense encompassing various performance forms and aesthetics. On the other hand, to break away from the fossilized modern dance technique and the authority of mastery, artists like the Judson Church group rejected virtuosic, narrative, and expressive choreographic approaches, as well as any confines to techniques, spectacles, and assumed spaces as written in Yvonne Rainer’s No Manifesto. Instead, they experimented with neutral, every day, mundane, and non-professional movement accompanied by scores. No doubt, to embrace their crucial contribution to postmodern aesthetics and strategies, it brought out an unintentional side effect for the next generation, giving authority to neutrality and critical logic over emotion. How much did we limit our emotions and dramatic impulses, and control them with critical thoughts to make coherent concepts and scores? In the current era, where the authority of art techniques and mastery has been eroded, what does it mean to perform technical movements, dramatic music, and expressions full of emotion and energy? What kinds of new aesthetics can it create?

We live in a society where expressing emotion is still considered irrational and vulnerable, and it has become something that we need to relearn. Watching a dance with emotion does not necessarily make the audience a passive viewer of the drama; instead, I perceived it as a reminiscent of indigenous ancient theatre aesthetics, which believed in immaterial communication between the body of the audience and the performer. This performance shared inexplicable emotions through dance without a linear storyline, thus allowing the audience to be freely moved by the performer’s emotions. We may need to believe and learn more about this type of telepathy between the performer and the audience, the feelings traveling between our bodies.