Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels is a monster of a festival. The sheer size and ambition of the festival (along with the popular tickets that you have to fight for) makes it difficult to grasp in its entirety. It’s also a monster in that it might eat you, if you’re an artist showing your work there. These are my reflections on a few works I saw during the festival and some of the different strategies artists took for how to navigate the festival market economy and how to deal with your marginalised identity becoming a commodity. Or in other words: How to not get eaten by a festival.

In the course of 23 days, the festival presented 34 artistic projects across 25 locations in Brussels. Almost every show was sold out a few days after the tickets were released. The programme is a testament to the festival’s international profile with artists coming from 26 different countries. Kunstenfestivaldesarts is one of the most well-renowned performance festivals in Europe. Hosting a total of 16 world premieres for this edition, many programmers have their eyes on the festival (over 450 programmers visited this year from all over the world). All this to say, that like many similar festivals around the world, Kunstenfestivaldesarts has also become a marketplace for the industry: the place to find the next new thing, to show at your own festival. When I asked a programmer from Greece what she thought about a show she had just seen, her simple answer was: “I wouldn’t buy it”.

As an artist you enter this festival market economy. You’ve made it this far: you’ve got your work curated by the prestigious festival and now you must sell yourself, stand out, be marketable. Some people I met even talked about ‘festival pieces’ that share a certain aura and can easily circulate in a festival infrastructure. Talking to different visiting programmers I met during the festival, I encountered a tendency in their language, where they would sound like they really supported artists from marginalised identities and communities, but the support felt superficial and instrumental. One programmer talked about wanting to program more shows with people from the ballroom community but didn’t really express an understanding of this same community. “You don’t like Madonna?”, she asked my friend from the ballroom scene. Afterwards she told us how we would both love the next show they’re doing at her venue. “It’s a show with disabled artists,” she said smiling, without going into further details.

This discourse among the visiting programmers probably (hopefully!) doesn’t reflect the actual curation of Kunstenfestivaldesarts, that seems well thought through, but the comments are symptomatic for an art world, that in the past years have had a big focus on representation but is still struggling to understand the identities and communities it wants to represent, making it potentially even more precarious and exploitative to enter this system as an artist. It makes me think: What kind of representation is possible? What are the terms you must present your work in as a marginalized artist? What kind of way are you expected to perform your identity, to make yourself legible to the institutions? How to deal with your identity becoming a commodity? Through this lens I want to look at three different works from Kunstenfestivaldesarts, that all seemed to me to present different more and less direct strategies for how to navigate these questions.

A) Deconstruction

Anarcasis Ramos, Mi madre y el dinero

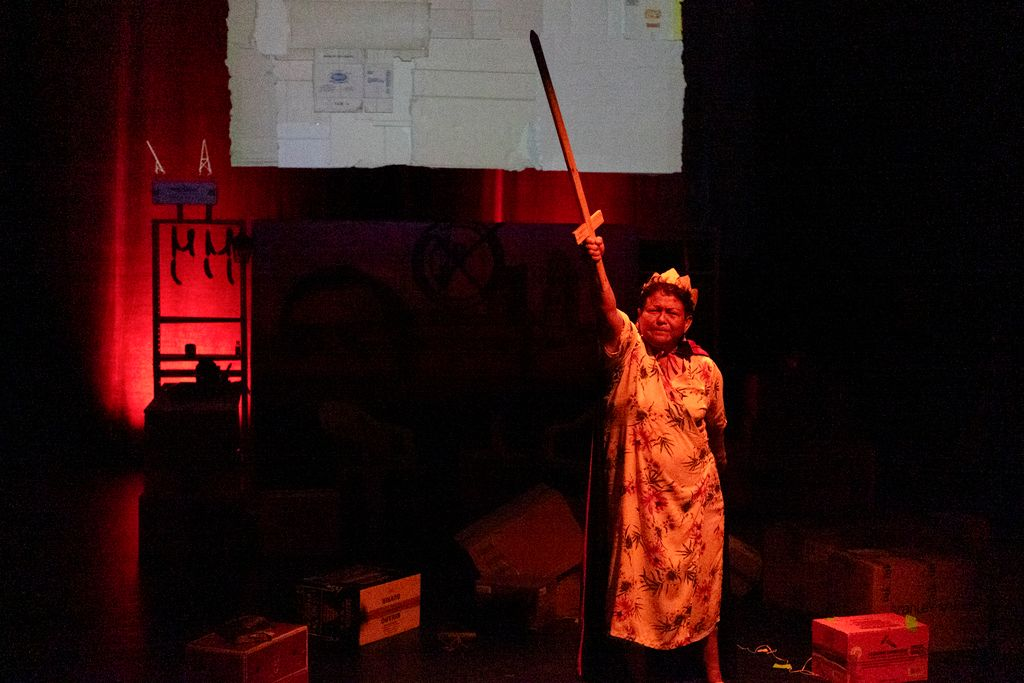

The piece responding to this commodification in the most direct way was Mi madre y el dinero (My mother and money) by the Mexican self-taught playwright and director Anacarsis Ramos, a self-described “child of commerce and violence”. The piece revolves around the artist’s mother, Josefina Orlaineta, who is on stage with Ramos, playing herself. Together they revisit and reflect on the more than forty jobs she’s had to have in her lifetime through a series of formats: re-enactments, conversations, a chorizo tutorial, a vlog for struggling artists, a dramatic monologue and more. Ramos jokingly presents the whole piece as a scheme to make money for his mum. Now Orlaineta can add the job title ‘actriz’ to her list.

While exploring his family’s personal history and relation to money, Ramos also investigates the exploitative nature of the art world. In one scene he directly addresses the context of showing his work at European festivals and how they expect certain types of third world works supporting their image of what that should look like[1], and how they instrumentalize his marginalized identity as an artist coming from a “poor working class racialized background” as well as being young, queer and neurodivergent.

In one scene Ramos and his mum are making Campeche-style chorizos while the TV is showing a self-made tutorial. In the subtitles we follow a separate narrative surrounding the domestic violence that Ramos grew up with from his father. When Ramos and Orlaineta is finished with the chorizos, they start selling them to the audience. “Special edition Kunstenfestivaldesarts,” they say, “Only 30 dollars!” “Come buy our trauma,” Ramos shouts. “You can also save them as an art piece.”

Throughout the play Ramos and Orlaineta deconstruct the images and roles that is expected in confident and playful ways. The tone of the piece keeps shifting between the sincere and the cynical, emotional and intellectual, sad and funny. It’s a harsh critique of the exploitative colonial logics of art world and the capitalist society as well as a celebration of love, family and resilience.

Towards the end of the piece, Ramos reads a letter to his mum saying how the whole thing really was just a way to get closer to her and share something together. How he’s tired of hearing her talk about how she’s failed him. Ramos concludes: “In the end I realized, all I could offer you, was a gentler version of your story – of our story.”

B) Ambivalence

Try Anggara, Dibungkus

Similarly to Mi madre y el dinero, Indonesian choreographer Try Anggara’s piece, Dibungkus, (wrapped) deals with the artist’s mother’s work, who ran a small restaurant in Jakarta for years. Anggara grew up learning how to wrap rice in folded leaves and in the performance, he explores the gestures and memories connected to this act of labour through dance.

The piece starts with a couple of performers folding paper and running across the stage. After some time, Anggara himself enters the stage and proceeds to do a sort of tutorial as part of the show. “Hello everyone and thank you for coming. Today I will do a presentation of this thing,” he says and points to a bundle of folded paper. He goes on to explain how his mother would teach him how to wrap rice, by wrapping rags instead, as to not waste any rice. He says he’s sorry for his bad English. “I’m always nervous when I’m talking. Friends help me!”. Out jumps four performers to introduce themselves. Everything seems very informal and intimate and at the same time performatively nonchalant. Each of the performers talk about where they’re from in Indonesia, while Anggara intercepts with “Yes!” or “It’s true!” donning a big smile on his face. Somehow the whole tutorial comes off as a sort of parody and at the same time it serves a pedagogical purpose, contextualizing the dance piece. “Okay enough talking!” Anggara says and demonstrates the rice pack folding technique. He wraps the rag in paper, puts a rubber band around the package and as a finishing touch pulls and lets go of the rubber band, making a sound that serves to tell the costumer that the package is ready.

“Okay, we move on to the next presentation,” Anggara announces and pulls the rubber band again. This time the light changes dramatically with the snap of the rubber band. From here on the performance turns into more of a typical dance piece. The performers take turns folding packages and folding their bodies with immaculate precision and doing different scores and poses in a kind of chorographical game dictated by the rubber band as a starting pistol. Snap! Snap! Snap! The rubber band goes as the performers kick, writhe, stomp and run through the space with an almost overwhelming explosivity and virtuosity. The whole thing feels very theatrical and makes a complete contrast to the intimacy and awkwardness of the preceding tutorial.

Soon the performers start moving into the audience, making the game more complex. They constantly have to keep on their toes and be ready for the next sound of rubber band, that makes up the sole soundtrack for the piece. Towards the end all the performers gather around one audience member as if they want to wrap them in a rice pack as well.

Dibungkus is difficult to place. The context of Kunstenfestivaldesarts is the first time the piece has been shown outside Indonesia, and I imagine the introduction has been added to the piece for this European context. But is the introduction sincere or ironic? Is it making fun of the commodification of his identity? Or our want to always understand everything? I’m left with an interesting ambivalence. Between the awkwardness of the tutorial and the virtuosity of the (almost too perfect) dance. Between the pedagogical explanation of the cultural context of what we just saw and the confusion about exactly what I just saw.

C) Exhaustion

Satoko Ichihara, KITTY

Japanese playwright and director Satoko Ichihara also plays with a strong cultural stereotype, wrapping her whole performance KITTY in a ‘kawaii’ (cute) aesthetic – a word that is also repeated again and again in the script until it loses its meaning completely.

As the audience enters a cat choir jingle plays manically in a loop. Freezer roll cages make up the scenography and the campy costumes are made from plastic scraps and animal print. Some of the performers wear enormous cat heads with plushies and tits for eyes, forks sticking out of their head. The characters move in weird twitches and lipsync all their lines as some sort of malfunctioning cyborgs.

In one of the first scenes, we follow the protagonist, a kid, having dinner with her parents. The dad loves meat, but the kid refuses to eat meat. One day the dad realizes the mum has served soy meat for them and rapes her out of anger. “Papa shows mama what meat is,” the kid narrates while the performer pulls out an extremely long cartoon-like penis. Soon the audience gets their dramaturgical revenge as Meat Person, a character that is made up of all the meat in their fridge (and looks a bit like a wrestler), comes back and kills the dad, whose blood splatters all over the stage. From here on KITTY delivers one extreme and absurd image after the other, exploring the intertwinement of cuteness and violence, the treatment of animals and the objectification of women, sex work and the food industry.

We follow our protagonist going through life and navigating all the sex and violence she is constantly exposed to and caught in everywhere she goes. At one point she gets a job as a secretary but realizes when her co-workers start having sex around her, that she’s not an ordinary secretary: she’s an extra in a porn film. This pattern continues for her, she thinks she’s at the dentist, but really, it’s porn, she thinks she’s taking the train, but it’s porn… “We are all extras in porn. We are participating in porn without knowing it,” she concludes.

The points and connections that KITTY makes are all very on the nose, but the performance pulls it off through its seductive campness and pure commitment to the same concepts it keeps returning to. (Another time our protagonist is on the train, and thinks that she’s in a porn again, but then it turns out to in fact be … murder). In the end KITTY takes another unexpected turn as Meat Person turns into a planet, that ends up hosting a cannibalistic utopian society, where people eat bites of each other until they eventually become one and start reproducing through cell division.

“I’m stuck in an unhinged loop,”, the cat Charmy says after a rant about wanting to kill everyone. The same can be said about the performance itself. KITTY is an unhinged spectacle, it’s flashy, fun, violent, absurd and it’s deliberately too long. Every time you think the performance is going to end, KITTY adds more stories and images until we enter a violence-fatigue and cuteness-fatigue. By the end of the performance a feeling of numbness arrives. And just as we can’t feel anything anymore, the performers break character inside the fiction to inform us that there’s merch for the show available, cute keyrings that we can buy for cheap when we leave the theatre.

… an incomplete guide

All three works by Ramos, Anggara and Ichara revolve around food, which is maybe symptomatic since it is the intersection between the body and the commodity. The artists are all at risk of becoming dinner for another monstrous European festival, but they try to change the menu and provide different strategies for navigating the expectations. Questions such as: “How to deal with your identity becoming a commodity?” is not at question that necessarily can be solved, but it is a premise that only seems to become more and more prevalent these years. This text is not really a guide, even though it tries to disguise itself as one. It is a way of trying to think together with the pieces, to look for possible strategies in an industry hungry for your trauma (with or without good intentions). An industry that sometimes knows what it does. Sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it might eat you by accident.

What are the possibilities? Do you deconstruct their limiting expectations to you? Do you force feed them your trauma-merchandise? Transform into a Meat Person and fight back? (or maybe turn into a planet and escape?). Can you exhaust them?

Or maybe you wrap them into neat little rice packs with rubber bands around them.

You pull the rubber band.

You release it.

Snap!

[1] Ramos recently made another piece connecting SpongeBob Square Pants and Beckett that defies this criteria.