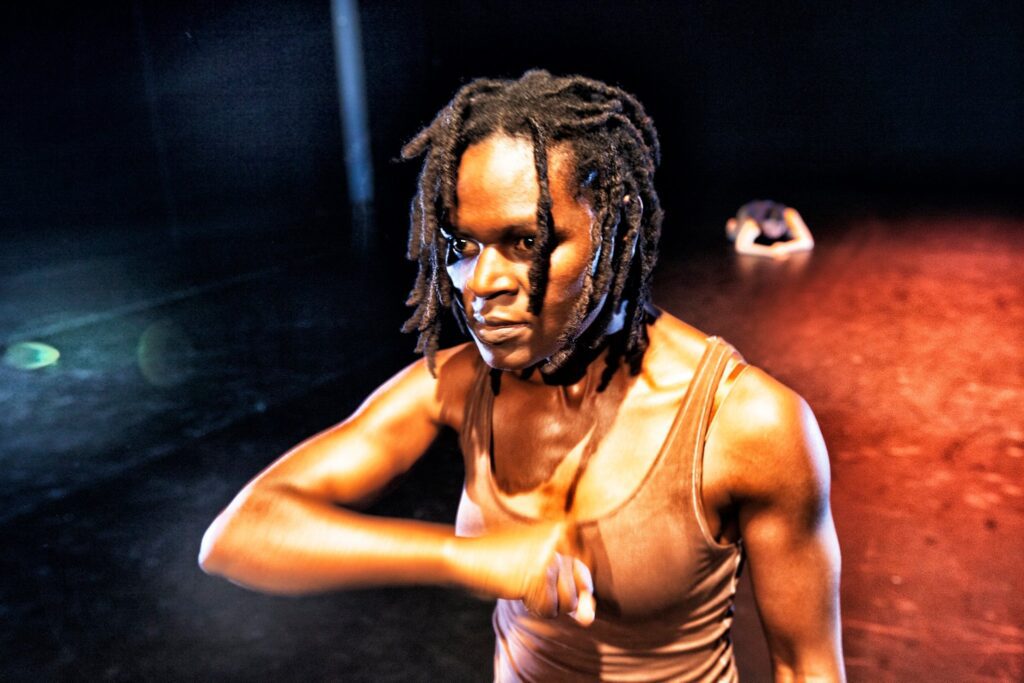

As part of her series ’Living Archives’ curator Lotte Løvholm interviews performer Julienne Doko about her latest work W.O.M.B. (Worth of My Body) (2022) and her journey as a dancer. Their conversation deals with motherhood, bodily changes and Afro-Atlantic experiences in Denmark as a dancer.

Lotte Løvholm: Thank you for doing this interview with me, Julienne! You both work as a performer and a choreographer and I came across your work for the first time quite recently when you were performing in Matilde Böcher and Jules Fischer Dryppende Stof (2021), and latest I saw W.O.M.B. (Worth of My Body) (2022), which is your own performance work. Would you explain the idea behind W.O.M.B.?

Julienne Doko: Uh, the seed! The first seed was planted by a painting by Michael Kvium. It was in 2014 and I was pregnant with my twins. I went to Aros in Aarhus where I stumbled upon his painting Natural Circle. The painting portrays a woman with saggy breasts, a skull on her head within a circle of lemons. The atmosphere is very gloomy and dark. The piece caught me off guard and I was drawn to it. Death is really present in the painting but also life obviously because I also see in it a body of a mother who has breastfed.

I was soon to give birth and questions of life and death were definitely something I thought about. First of all, am I going to survive giving birth, given it was a double pregnancy? Will I be a good mother? What are going to be my values? I’m a Central African and French in Denmark, raising kids in Denmark. What is going to be my legacy? How am I going to pass on traditions from my native culture? All of those questions were in my head.

LL: And this was your first time becoming a mother?

JD: Exactly. And I was a zombie for a year of course with twins! I had to stop dancing for a while, but dance was still there. I had so many emotions to process and I needed to put that in movement. 2 years after I gave birth in 2017, I started thinking about the painting while reflecting on what was happening with my body. It was incredibly painful giving birth, right? Your body will never come back to how it was before and having to accept that, because you never know how your body is going to react to pregnancy. As a dancer and as a performer I’m used to exposing my body. So I was wondering, if I was going to be at ease. All those questions I needed to put into movement and I knew I needed other women to tell those stories too.

LL: You reached out to colleagues Meire Oliveira and Naa Ayeley…

JD: Yes. My friend and colleague Meire had given birth for the second time a few years before and I had met Naa who had also given birth not so long ago. I explained my longing to them of making a piece about motherhood and the relationship to body changes as dancers and as foreign women from the Afro-Atlantic World. This is something I’ve never seen personally on stage. And they said yes!

LL: Could you explain your consideration about the presence of the postpartum body in the performance?

JD: I wanted the body to be visible with stretch marks and all which was a challenge for myself because I’m not super at ease. My mother is an ethnolinguist who has studied my native culture and language for 40 years. She is the expert. She knows way more than me. I moved out of Central Africa when I was 4 years old and grew up in France. I asked her how do we say stretch marks in Gbaya? And interestingly the word for stretch marks is a combination of tattoo and god or ancestors (tattoos of the ancestors). That really changed how I viewed the postpartum body. I had learned that stretch marks were something I should hide, but instead it could also be something of pride.

In terms of the vocabulary for W.O.M.B. I wanted it to be powerful and very expressive. Becoming a parent is a roller coaster. It is the responsibility of a lifetime. And you remember the pain that is engraved in your body. There is a loss of control over your bodily functions and new bodily limitations as it takes time to gain back strength. I like jumping. I couldn’t really do that for a while. Jumping and turning at the same time I tried once. I can’t do that anymore. I’m not even trying anymore at this point. We have to relearn how to move in a different body. I had to learn to dance again with my new limitations.

I wanted to fit in some of the movements I made in 2017 processing motherhood and some of them are signature phrases that we do together. The first one I made is like a roar. But there are also sections where we create our own movements and do solos to insist on having 3 different perspectives.

LL: You also work with different sound elements?

JD: We have a live musician composing the scores, Gert Østergaard Pedersen. He is a great composer. And vocal sounds are also super present in the piece. With pregnancy and labour, breath is so important. I wanted the piece to be very sensory in that sense. There is a section, which I called the haka inspired by Māori dance (Julienne emulates the movements and sounds). I like what the dance represents: calling upon strength, togetherness, unity, but also changing destiny through movement.

LL: I appreciate you mention the ritual elements of the performance. As you said this piece deals with themes that are not that exposed like motherhood, bodily changes as dancers in the Afro-Atlantic diaspora. You are manifesting togetherness by highlighting these matters in the performance and I was wondering how the reception has been?

JD: The response has been amazing. And not just from mothers. Also men. I have friends who came with their daughters and the piece became a conversation starter about body intimacy. I’m so happy about that.

LL: The work is super powerful!

JD: Thank you.

LL: I want to ask you how you started working as a dancer?

JD: I started like many people, taking ballet classes when I was six in France. But my body did not like it. The first position for me… Like, I cannot force it too much. There is a limit to my first position. It was so painful for me. It was back in the 80s and there was not that much awareness of the importance to embrace different body types and abilities in dance. After that I started jazz. My body preferred jazz and I continued practicing till I was 18 and moved to Paris where I discovered Hip Hop. I trained a lot in Paris and New York before moving to Portland, Oregon, for my studies. I did my masters in English and then in French literature. In the States I discovered other dance styles like Samba, Afro-Brazilian, Afro-Cuban and African Dance from Guinea.

After Portland I moved to Canada where I discovered African Contemporary Dance. I was scared at first because for me contemporary was equal to ballet. But luckily, I went to a class and realized I could do this. And so I trained in Zab Maboungou’s technique.

I grew up with ballet and to me ballet meant technique. But of course, technique is in all the dances. It’s not just a European thing. With Zab, I came to realize that African dances also have techniques. From then on, I would look at traditional African dance from a technical point of view, which completely changed my understanding of movement and my practice.

After Montréal, I trained in Brazil for a year in the Silvestre Dance Technique and then I moved here and started teaching dance. The dance schools in Copenhagen were interested in traditional West African dance as I suggested that it was complementary to their dance program. In my teaching I would emphasize the technical side of the dance and connect it with techniques from modern dance, contemporary, jazz and hip hop. I soon felt I was put into this box of African dance in Denmark. That was ten years ago. It became too restrictive for me so after three years, I was like: “I’m out of here”. I’ve said that many times, but the Danish dance scene was way more closed before than now, especially contemporary dance. After I left, I went to dance with Zab Maboungou in Montréal in her company and I also started developing more of my own projects.

LL: Yeah! And you are back in Copenhagen!

JD: I was in Canada for two years and then back to Brazil for a year before returning to Denmark in 2014. I was pregnant and I said to myself, let’s see how it goes this time. If the scene has not opened up, I’m out of here again. But things are changing.

LL: Do you feel you get placed in the same restrictive box?

JD: Maybe still a bit. But at the same time, I think that the scene in general understands the connections between different dance styles, performance and dance. And that has always been my approach. I have always been working with different styles while collaborating with many different performers and travelling all over the world. I’ve been used to dance scenes abroad where people just reach out to you because they are curious about your practice. That did not happen here at the time, at least not in my experience.

LL: I wonder about the differences for you in terms of working for others and producing work yourself: Do you prefer one to the other?

JD: First of all, I love working in environments with different expressions because it gives me an opportunity to challenge myself: “How do I fit my dance vocabulary into this?” It is always interesting for me to be invited. I would say if I could just be a performer that would be fine by me, but I need to create. It is an urge, but it is a lot of work.

LL: We have both been working with artist Jeannette Ehlers a lot. How has the experience been performing on a busy shopping street in Copenhagen in her work We’re Magic We’re Real compared to the settings you are used to?

JD: I love working with Jeannette. She has a great artistic vision. As a dancer it is nice to evolve and it requires a different focus to perform on a busy pedestrian street. The audience is close to you, which of course is very different from being on stage. You see people walking by not paying attention to you for example. Not everybody will listen to you, but some people will stop and listen. You will have to decentre yourself even though you are centred on the street with things happening around you.

LL: It is an interesting point how the audience plays different roles in different contexts. In this piece you engage with people that may never buy a ticket for dance performance.

JD: Exactly. It has also made me think more about performance art in my own practice. Usually, I will think of gestures to express certain things but currently I am taking the setting, the audience and text more into consideration. For my next project called Journeys at Den Frie in June 2023 I have invited five other performance artists to present short pieces. It will be a string of performances with Jupiter Child, Sall Lam Toro, Phyllis Akinyi, Wanjiku Seest and Jeannette Ehlers.

LL: Will you also do a piece?

JD: I will remount a piece I created in Montréal.

LL: I am looking forward to that and thank you so much for speaking with me, Julienne!

Living Archives

Living Archives is a series of conversations organized by curator and writer Lotte Løvholm with performance artists and researchers. The purpose of the conversation series is to highlight stories that are easily forgotten when art history is written:

“I will attend here as well then, to the ways in which art criticism has tended to leave out specific histories, and thus specific bodies, in order to purvey supposedly “new” ideas about art trends. The stakes here are high, because the histories that get told, and the ways in which they get told, determine what we remember and how we construct and view ourselves today.”

Amelia Jones: “Unpredictable temporalities: the body and performance in (art) history”, Performing Archives / Archives of Performance, 2013.

More from Lotte Løvholm