“Examine your own nature, stretch your own body out on the examining table, do the work that needs to be done on yourself (with all this charge’s intended multiple meanings), and discover the seams and sutures that make up the matter of your own body. Materiality in its entangled psychic and physical manifestations is always already a patchwork, a suturing of disparate parts.” – Karen Barad, Transmaterialities – Trans*/Matter/Realities and Queer Political Imaginings

Agnes Questionmark (b.1995) constitutes her own embodiment, narrative, and mythology. From the beginning of the artist’s practice, she has used her journey of coming into being as the focal point of her work. As spectators, we are granted the opportunity to witness her evolution from her birth assigned sex to female, womb to the flesh, from gestation to her fluid, transitional state of becoming. She embodies and confronts us with the pressing contemporary capitalist realities, biotechnologies, and the paradoxical technological organic condition of the 2020s. Her performative practice challenges the fixed notion of what a body is, producing counternarratives and counter-representations encircling Preciado’s aim of challenging the perception of the body by intervening collectively and critically through a network of researchers, biohackers, artists, and other collaborators. Questionmark can be inscribed into a methodological and artistic tradition exploring biohacking, post/trans-humanist inquiry, and transformation of the body within a queer and performative context, akin to the practices of Matthew Barney, Rebecca Horn, Eduardo Kac, and Lynn Hershman Leeson. She rejects the rigid medium-based structures of the art world, instead using her body as a site for exploration and a laboratory for transmedia and transspecies investigation. A key focus of her current thematic inquiry, which will serve as the foundation for the essay, is Questionmark’s critical analysis and examination of medical practices through a queer lens, representing a new site of exploration within performance art.

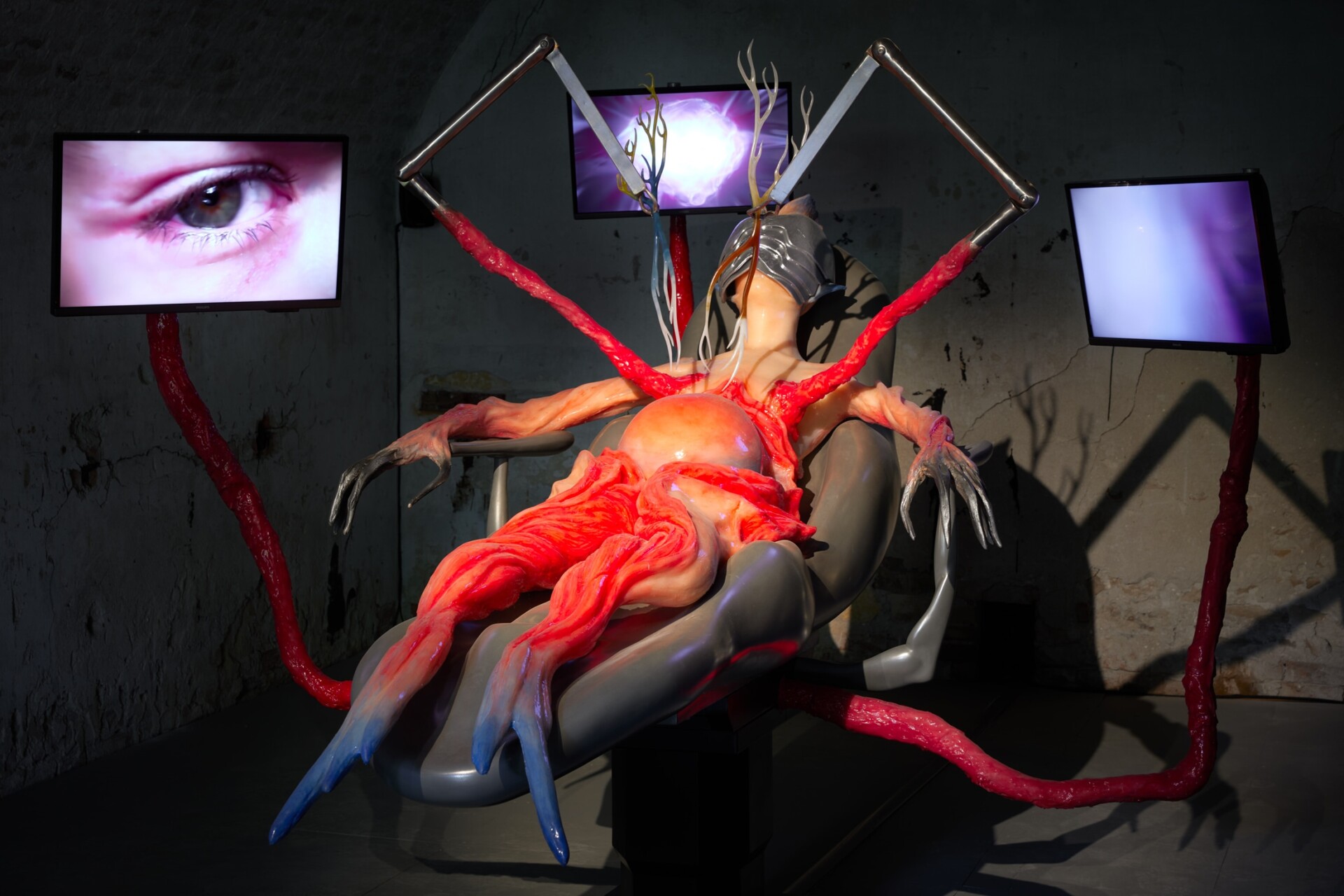

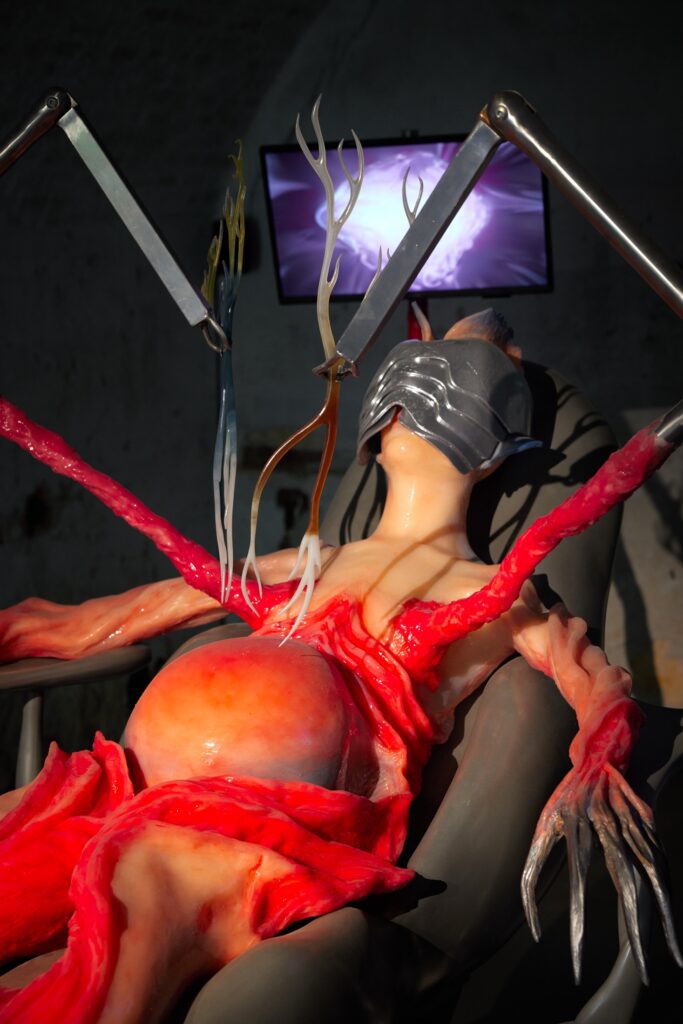

Her practice is shapeshifting, resulting in long durational performances, visceral sculptures that are both captivating and repulsive, video works, and biotechnological experiments such as her work Questiongen, in which she extracted her DNA and made it into pills. She has previously exhibited at the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva and the MAXXI Museum in Rome and is currently exhibiting her installation piece Cyber-Teratology Operation (2024) at the 60th Venice Biennale. On an August afternoon, Agnes and I connected over FaceTime to discuss her artistic practice, research, and future aspirations. As she strolled through the streets of New York City, her distinctive, black-rimmed cat-eye glasses framed her face. Our conversation started in medias res, as she animatedly explained her upcoming projects, the weather in the city and her afternoon plans. She is currently in New York, pursuing an MFA at the Pratt Institute.

Paul B. Preciado defines our contemporary condition as one dominated by a “new hot punk capitalism”, where an amalgamation of micro-prosthetic technologies shapes our subjectivities through biomolecular (medications that affect our bodies) and multimedia technical (digital media, like social media or video content) protocols. Micro-prosthetic technologies can be understood as the contemporary technologies that not only shape our bodies, but our existence. Medicines such as hormones and antibiotics, contact lenses and hip replacement surgery are all micro-prosthetics that prolongs, optimizes and alters our corporeality and disbands the juxtaposition of natural and artificial. An economy thriving on the circulation of the “[…] hundreds of tons of synthetic steroids and technically transformed organs, fluids, cells (techno-blood, techno-sperm, techno-ovum, etc.).” In this context, technoscience, a fusion of modern technology and science, exerts its material power by redefining concepts such as psyche, libido, gender, and sexual identity, thereby transforming femininity, masculinity, heterosexuality, homosexuality, intersexuality, and transsexuality into material realities.[1] This, in turn, changes the properties of the contemporary subject regardless of health/pathology by subverting its ontological status and redefining it as a biopolitical and performative subject.

According to Preciado, the contemporary body is a site of political and social intervention, […] a somatheque: a dense, somatic, stratified, organ-saturated apparatus managed by different biopolitical regimes that establish spaces for action that are organized according to class, race, gender or sexual difference.”[2] Shaped through a multifaceted interaction of discursive, scientific, pharmacological, economic, and visual practices, the somatheque is a medium for political control and capitalist production. The regulation and governance of bodies through medical, technological, and pharmaceutical entities illustrate how changes in corporeality are closely related to societal power structures. However, somatic interventions (like hormone therapy) become acts of resistance against normative gender frameworks.[3] I position Italian artist Questionmark within this counter-narrative of techno-sciences and performative subjectivity, in which she navigates questions of hybrid identities and trans-speciesism. Trans-species refers to the conceptual blurring or crossing of boundaries between species, challenging traditional distinctions and hierarchies in the natural world. It indicates a fluidity of identity and an interconnectedness between humans, animals, plants, or other forms of life, conceptualizing the complex entanglement of all living beings.

Olivia Turner Saul [OTS]: Your work seems to have a strong research foundation, particularly considering your background. Could you elaborate on the role research plays in your practice? Would you say your work is predominantly informed by trans-speciesism, or do other theoretical frameworks shape your artistic approach?

Agnes Questionmark [AQ]: “ I have begun to perceive my creatures and sculptures as autonomous identities, with their own lives and agency transforming. My practice is not confined to a singular theoretical perspective; it draws from multiple areas, including trans-speciesism, which I have explored for several years. Additionally, I engage with the concept of trans-corporeality, particularly from a queer standpoint – viewing it through the experience of someone reliant on artificial apparatuses for existence. My identity is shaped by my role as a patient and my access to medical treatments. The scientific and medical world has a profound influence on my existence, and I utilize that framework as a tool for self-construction. I approach artificiality not only as something human-made and reproducible but also as a fundamental aspect of human nature. We are inherently artificial beings, not only because of the natural world but because we continuously construct, reconstruct, and build ourselves”.

In her graduation piece, Portrait of the Homo Aquaticus (2018), Agnes Questionmark presents herself submerged in water, surrounded by water cabbages and long leaf speedwells, enclosed within a wooden aquarium. The performance evokes the imagery of fetal gestation, with the artist breathing through a tube, allowing spectators to witness the emergence of the homo aquaticus. This figure, a mythological being of Questionmark’s creation, is central to her practice of world-building. Through this fictional birthing narrative, she constructs a space where imagined life forms challenge and expand normative understandings of the human body and its place in the natural world. Karen Barad introduces the concept of trans-materialities, taking a point of departure in their earlier writing, where they argue that materiality is inert and constantly in flux, always in the process of becoming something else, shapeshifting, and forming new realities.[4] Bodies, human, animal, or otherwise, emerge through their material and social entanglements with other bodies; they are not fixed entities but processes in constant motion. Trans bodies exemplify the inherent fluidity of materiality, rejecting binary frameworks by illustrating how bodies are sites of ongoing transformation and potentiality entangled with material processes.

In a previous interview, Questionmark described her genesis as an act of myth-making stating, “I am indeed writing and composing my mythology. I am the narrator and the actor, the doctor, and the patient. I choose to use my body as a test subject for my experiments. I live my science fiction, empowered by a new name, identity, and rewritten biology.” [5] It was in the water Questionmark came to be; water becomes the facilitator and the gestational milieu, akin to a child in the womb. As stated by feminist and theorist Astrida Neimanis, progenitor of hydro-feminism, water sustains our bodies and tethers them to other bodies and other worlds beyond our human selves. Water is a body of queerness; water is simultaneously finite and inexhaustible, constantly changing form (condensation, ice, liquid, etc.), proliferating and transforming all bodies. This exposes us to the fact that we are not static; we contain and expel water, take form in amniotic waters, and absorb and circulate water within and outside our bodies. All human and non-human bodies are permeable membranes, and water serves as a connector because it expresses or facilitates difference.[6] However, where, i.e., Neimanis and writer Luce Irigaray present gestational bodies of water as feminine-maternal, Questionmark refutes this through her work, where water becomes a non-binary body of potential.

Earlier works such as Squid Dinner (2018), Colonizing the Ocean is Not an Easy Task (2019), and Sometimes I Think I Should Be More Like a Fish (2020) explore questions that transcend binary gender constructs, positioning themselves within a lineage that includes artists like Joan Jonas (b. 1936). Much like Jonas, whose practice often blurs the boundaries between human and non-human forms while engaging with feminist and ecological themes, Questionmark’s work interrogates notions of fluid identity and embodiment, particularly through the lens of marine life and its symbolic relation to gender fluidity. This thematic resonance situates Questionmark within a broader tradition of artists who challenge anthropocentric perspectives by merging ecological and gender discourses. Questionmark presents speculative mythologies centered on our species’ ability and willingness to adapt to unknown climates and environments like the sea: “The sea leads human beings into a more unified creature, not one who seeks separation and self-gratification but one who seeks coalition and collaboration.”[7] Our conversation is dynamic and although we speak virtually, I can sense Agnes’ charisma and curiosity through the screen. Her words are spoken softly with a characteristic Italian quickness, as she simultaneously navigates our conversation and the pavement before her.

OTS: Looking at your recent works, the audience is watching you transition through your different pieces. For example, in your graduation show, Portrait of the Homo Aquaticus, and then moving through your thematic development, it seems like you transitioned from the sea to more machine-focused, medical-focused work. Is there a correlation between this development?

AQ: “I view these two elements – nature and technology – as symbolic of my father and mother. While the sea is often traditionally associated with femininity, for me, it represents my father, who taught me to dive and fish. Growing up on a boat, I developed a profound connection with the marine world, often imagining myself as one of its creatures. The sea became a gestational, protective space, offering solace when I was uncertain about my identity. However, my transition into becoming Agnes was akin to a real birth; it marked a significant moment of transformation, yet I remain in a continuous process of self-definition. My works are an exploration of this desire to become something else, to articulate my evolving identity. The octopus, for example, has come to symbolize empowerment for me due to its capacity for transformation. But I also came to realize that my identity is not solely natural; it requires active construction and maintenance. ‘Agnes’ is an identity that will always be in flux, always shifting. What I’m striving for in my work is a fusion of the mechanical and the organic. Take Cyber-Teratology Operation (2024) exhibited at the Venice Biennale, for instance – it’s an organic form that incorporates marine biological features alongside mechanical and technological elements. These two aspects need to coexist in my work, and I think this combination of the mechanical and the organic will be something I keep exploring in my future work”.

Contemporary bodies, in all its forms, is an extension of global technologies, a technological system that can be perceived as an implosion of binaries (female vs. male, animal vs. human, nature vs. culture, natural vs. artificial).[8] The transgendered body is a true embodiment of this techno-living system. Questionmark stance on the transgender body and its potential can be seen as drawing close parallels to that of author Susan Stryker in her piece My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage, Stryker reflects on the experience of being a transgendered woman, drawing a powerful analogy between her own body and the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Stryker describes the transgendered body as one shaped by medical science and technology, a form intentionally reconstructed beyond its original state. She finds a sense of affinity with the creature of Frankenstein, highlighting how both are assumed to be less than fully human due to their bodies’ “artificial” nature. Stryker also speaks to the societal rejection faced by both her and the ‘monster’, which fuels a rage directed toward the circumstances of their struggle for existence.[9] Despite being labeled as ‘monsters’ and denied full personhood, Stryker reclaims this identity:

“I find no shame, however, in acknowledging my egalitarian relationship with non-human material Being; everything emerges from the same matrix of possibilities. ‘Monster’ is derived from the Latin noun monstrum, “divine portent, itself formed on the root of the verb monere, ‘to warn’.[10]

In Simone de Beauvoir’s conceptualization of the Other, the societal construct and positioning of the female body as other to the male body, the ‘self’, one can further develop this within a contemporary context of the transgender body and queer identities. The queer and trans embodiment is, through a societal lens, often seen as the other, pitted against the cis-and heteronormative ‘self’. Beauvoir’s analysis of how society constructs the ‘Self’ by establishing an ‘Other’ illustrates how dominant norms produce and reinforce the marginalization of queer and trans people.[11]

Attempt I (2023) embodies monstrosity, transgender rage, and the rebirthing of oneself. Questionmark is wrapped in plastic, resembling an artificial womb. Her body is submerged in amniotic fluid, splayed out on a medical stretcher while writhing her body in pain and discomfort. She is a hybrid pregnant being, her belly dysmorphic, and her tentacles floating. A doctor draws a knife through the artificial placenta, the plastic enclosing Questionmark, in which a rush of liquid is discharged, covering the floor of the clinical room, followed by an incision to the uterus where alien-like creatures are birthed cesarean. Questionmark, presenting herself as a monster, an alien, a trans-species entity, succumbs to the birth of the creatures. Questionmark challenges rigid gender binaries and sexual norms, thereby embracing freedom against the deterministic ‘Othering’ of non-conforming identities. In this sense, Questionmark demonstrates how queerness and transgender embodiment become an act of resisting the process by which society forces individuals into predefined categories, offering instead a multiplicity of ways to exist beyond normative structures. This failed experiment can be understood as an allegory to the transgender rage, the rage that both Barad and Stryker institutionalize. The painful birthing of transgender rage, in the words of Barad, in turn, becomes the womb through which she, in this case, Questionmark, rebirths herself. This can be understood in terms of Barad’s writing on a radically queer configuration, a queer origin story which they compare to nature’s birth out of chaos and void, an echo reverberating a birthing that is already a rebirthing.[12]

OTS: Your performances seem to explore themes of transformation and the merging of natural and artificial. How do you view the transgender body within this context, and what potential do you see in embracing a trans-species identity?

AQ: “My practice is based on multiple things, including trans-speciesism, which I’ve been exploring for a few years. I’m also delving into trans-corporeality, but from a queer perspective—through the lens of someone who needs artificial apparatuses to confirm and exist. I exist because I am a patient and because I have access to medicines. I’m shaped by the scientific and medical world, and I use that as a tool to exist. I consider artificiality as something non-human-made, something reproducible or constructed. But I also think we, as humans, are artificial—not just by nature, but because we need that artificiality. We construct, reconstruct, and build ourselves. I enjoy shaping who Agnes is and allowing it to evolve. It’s about not fitting into a rigid system but being able to change and play with my physicality, like changing my hair or altering my hormone use”.

As previously mentioned, Preciado defines the contemporary condition as punk hypermodernity, a radical and subversive response to the hypermodern era, which is characterized by an intensification of capitalism, technological advancement, and control over bodies. Questionmark’s practice is punk, where she takes a rebellious stance by challenging and critiquing not only systems of power but technological systems of control and commodification. Her exploration of the somatheque, potentials of corporeality, and the subversion of artificiality chimes in with Preciado, who posits: “We live in a punk hypermodernity: it is no longer about discovering the hidden truth in nature; it is about the necessity to specify the cultural, political, and technological processes through which the body as artifact acquires natural status.”[13] In Questionmark’s recent work Cyber-Teratology Operation (2024), she challenges societal perceptions of the presumed artificiality of trans bodies, highlighting how transgender bodies are frequently pathologized, mechanized, and medicalized. As noted by curator and writer Kostas Stasinopoulos, Questionmark, through this installation, critiques the patriarchal biopolitics embedded in science, technology, and healthcare.[14] The installation, subtly referencing artist Lynn Hersham Neeson’s career-long concern with technological surveillance and control, is comprised of a trans body, meaning not just transgender, but transspecies, transhuman, trans-corporeal. In an operating room, the viewer is confronted with a pregnant creature under surveillance; three screens surround, and images of a batting eye, skin, and the inside of the body oscillate, iterating Questionmark’s recent experience of overseeing an eye operation and the pathologization of trans embodiment:

AQ: “I become the tool, the doctor, and the machine. This is something I’ve experienced both as a patient and as a spectator. Recently, I was in Berlin to oversee a surgery, which turned out to be one of the most powerful experiences I’ve had. It was a robotic surgery, something I’ve been researching. The surgeon was controlling the machine like a game, and the only organic element in the room was the eye being operated on. Everything else was technological—machines, sterile equipment, doctors in masks and gloves. The contrast was striking, with the eye wide open, almost as if it were being surveilled. To me, the surgical room is a space where identity, politics, and societal norms collide. The surgery itself magnifies authoritarian roles, blending the human, non-human, and machine into one convoluted process. In such a setting, the distinctions between these entities disappear entirely.

Kosta Stasinopoulos helped me realize that my work often turns the viewer into a doctor or scientist. This transformation happens constantly—whether on the street, in a museum, or in a bar. Spectators become people who scrutinize trans bodies, evaluating their anatomy as if they were doctors assessing a patient. It’s a fascinating dynamic: trans people, in these public spaces, often turn viewers into doctors—people who look at their hands, their shoulders, their Adam’s apple. Suddenly, everyone adopts a clinical gaze, assessing trans bodies with a scientific, analytical approach. When I started performing with other trans people, we realized how much we enjoyed playing the role of doctors. There was something so cathartic about it, stemming from our shared frustration with how trans people are bound to the medical world—through surgical procedures, hormones, and the authority of doctors who have the power to validate and define our identities. The doctor holds immense power, and navigating that system is part of our lived experience. By embodying the role of doctors ourselves, we were flipping power dynamics, adding irony to the mix, and enjoying it, even if we didn’t fully understand what we were doing at the time. I drew inspiration from William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, where he depicts doctors in exaggerated, ironic scenarios—surgical operations taking place in bathrooms, bizarre transformations. Preciado also draws an analogy between drug addicts and trans people, suggesting that hormones function like drugs necessary for survival. In Naked Lunch, Burroughs presents a surreal and ironic depiction of doctors, which resonates with my approach. Similarly, my work aims to rewrite the narrative using humor and parody. For instance, in the SAM project, I found joy in filming operations in my studio, creating videos with a certain kitsch quality—almost a horror aesthetic. I also make collages and wall pieces that reprocess images into something funny. To me, it’s important to channel frustration with a sense of humor rather than always being serious”.

Although Agnes Questionmark’s focus has shifted more towards technological instruments, and spaces of medical interventions, creatures of the sea have been consistent imagery in her earlier work. Mermaids, octopi and aquatic-like beings have all had a presence in her practice, creatures that all have transformative and mythical qualities. In CHM13hTERT (2023), Questionmark performed as a mermaid-esque creature, her pink and blue aquatic body and fins glistening under the harsh lights of the Lancetti Train Station confined to a glass cage. Presented by curatorial collective and public exhibition space spazioSERRA, she was suspended for twelve hours a day for sixteen consecutive days, in a surgical hoist meant for large animals in the ticketing hallway of the station. CHM13hTERT is a specially developed cell line that serves as a model for investigating various components of the human genome. Scientists have made these cells immortal, allowing them to divide continuously without dying, which facilitates the exploration of potential treatments for a range of genetic disorders. Once the genome is analyzed, it can be altered and replicated indefinitely, enabling researchers to view our DNA as adaptable and subject to modification. Questionmark initially considered the performance a combination of a science laboratory and a nursery room, but soon realized it was more like a zoo cage, evoking connotations to 19th -20th century circus sideshows exhibiting caged ‘freaks’ and ‘monsters’.

AQ: “The passerby, part of a voyeuristic relationship with me, subjected me to an almost medical-scientific scrutiny. The spectator, the common passerby, unconsciously became a scientist, taking pleasure in my suffering and objectifying and sexualizing my hybrid and transsexual body. Like a monster in a circus, I was exposed to the judgment, laughter, scorn, and appreciation, as well as the fury and delight of all who took the train or visited the Lancetti station to see its chained siren. They called me the Lancetti Siren. I became the legend and mythology of the station and was surprised at how the photographs and videos of the performance traveled between devices and algorithms, triggering the insecurities and projections of millions and millions of people”.[15]

After one and a half hours of conversation, a theoretical ping pong tournament between the two of us, Agnes having referenced inspirations, professors, thinkers and collaborators, all who have shaped and continue to shape her practice, she arrives at her destination. A coffee date with a friend. Our conversation exemplifies the dynamic nature and actual world building (although an overused buzzword) that entails her practice. Agnes proves that her practice like the genome CHM13hTERT is malleable, constantly exploring potentials within bodies, politics and gender. She is the scientist and specimen, doctor and patient constantly pushing her own corporeal boundaries and how we understand performance art, pointing towards a speculative future that is less confined and rigid.

[1] Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, trans. Bruce Benderson (New York, NY: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2016). 32-34

[2] Paul B. Preciado, “Dossier Somateca,” in Advanced Studies in Critical Practices Somateca (Museo Reina Sofia, 2013), https://azaharaubera.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/dossier-somatecx-1.pdf.

[3] Preciado, Testo Junkie. 40-41

[4] To read more on materiality, refer to Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

[5] Jagrati Mahaver, “Agnes Questionmark,” Coeval Magazine, 2023, https://www.coeval-magazine.com/coeval/agnes-questionmark-spazio-serra.

[6] Astrida Neimanis, Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, Paperback edition, Environmental Cultures Series (London New York Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019). 2-4

[7] Agnes Questionmark, Colonising the Ocean Is Not an Easy Task, 2019, 2019, https://www.agnesquestionmark.com/colonising-the-ocean-is-not-an-easy-task/.

[8] Preciado and Preciado, Testo Junkie. 44

[9] Stephen Whittle and Susan Stryker, eds., “My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix,” in The Transgender Studies Reader (Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2013), 244–56.

[10] Whittle and Stryker. 247

[11] Simone de Beauvoir, Howard Madison Parshley, and Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (New York: Vintage Books, 1989). 17-20

[12] Karen Barad, “TransMaterialities,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21, no. 2–3 (June 1, 2015): 387–422, https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2843239. 393

[13] Preciado and Preciado, Testo Junkie.

[14] Kostas Stasinopoulos, “AGNES QUESTIONMARK,” La Bienale Di Venezia, https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2024/nucleo-contemporaneo/agnes-questionmark.

[15] Alessia Baranello, “To Take Part in the Shipwreck | A Conversation with Agnes Questionmark and Arturo Passacantando on CHM13hTERT and Other Stories,” Juliet Art Magazine, June 5, 2023.

Bibliography

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

———. “TransMaterialities.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21, no. 2–3 (June 1, 2015): 387–422. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2843239.

Baranello, Alessia. “To Take Part in the Shipwreck | A Conversation with Agnes Questionmark and Arturo Passacantando on CHM13hTERT and Other Stories.” Juliet Art Magazine, June 5, 2023.

Beauvoir, Simone de, Howard Madison Parshley, and Simone de Beauvoir. The Second Sex. New York: Vintage Books, 1989.

Mahaver, Jagrati. “Agnes Questionmark.” Coeval Magazine, 2023. https://www.coeval-magazine.com/coeval/agnes-questionmark-spazio-serra.

Neimanis, Astrida. Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology. Paperback edition. Environmental Cultures Series. London New York Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

Preciado, Paul B. “Dossier Somateca.” In Advanced Studies in Critical Practices Somateca. Museo Reina Sofia, 2013. https://azaharaubera.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/dossier-somatecx-1.pdf.

Preciado, Paul B., and Paul B. Preciado. Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. Translated by Bruce Benderson. New York, NY: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2016.

Questionmark, Agnes. Colonising the Ocean Is Not an Easy Task. 2019. https://www.agnesquestionmark.com/colonising-the-ocean-is-not-an-easy-task/.

Stasinopoulos, Kostas. “AGNES QUESTIONMARK.” La Bienale Di Venezia, n.d. https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2024/nucleo-contemporaneo/agnes-questionmark.

Whittle, Stephen, and Susan Stryker, eds. “My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, 244–56. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2013.

More from Olivia Turner Saul