We’re each in our own living rooms, I in Copenhagen, Candela in Barcelona, separated by a screen and a few thousand kilometers. I hadn’t had my pre-cigarette yet, and for a brief, performative moment, I worried it might seem unprofessional to light one. I held off. But cravings have their own logic. A few minutes in, I caved, lit up, laughed, and immediately apologized. Candela smiled, disappeared off screen, and returned with her own tobacco. Now we were aligned. Two ashtrays on each of our desks, and we were now ready to begin.

Candela Capitán (b. 1998) was born in Sevilla and now lives in Barcelona. Her performances, Instagrammable, hyper-mediated, and impossible to detach from the glow of a screen, have brought her international recognition. Trained as a choreographer at Institut del Teatre, she now tours widely with work that doesn’t so much resist the digital as fully absorb it. Exhibition space becomes feed. Choreography becomes scroll. Through platforms like Instagram and TikTok, Capitánstages femininity as both spectacle and glitch, using her own body as a tool to stretch, distort, and reframe the codes it’s meant to follow.

Olivia Turner [OT]: Social media plays a huge role in your work. It seems to be as integral as the physical, live performances. What is it about social media that you find so compelling as a medium, and how has your relationship with it evolved?

Candela Capitán [CC]: In the beginning, I was creating works specifically for social media. Now my approach has changed. I’m more interested in exploring how social media is actively shaping contemporary society. My work has become more critical. I’m no longer translating performance into digital form. I’m placing the structures of social media into live theater. It’s a reversal of how I began. Initially, I saw only the benefits of social media. Most people around me didn’t believe it had any value for us as artists. But for me, it was essential. It connected me to others, gave me visibility, and offered a platform for experimentation. I thought social media was a bridge, a way to reach an audience that might otherwise never step into a theater. But over time, I began to observe more critically. I now view it from a distance, as a system deeply entwined with how our society has grown obsessed with screens. We no longer experience life directly; instead, we mediate it through devices.

I had the opportunity to experience Capitán’s latest performance, XACT1.Content Cage, at inter.public in Copenhagen, marking the first time I encountered her work in a physical setting after having previously followed her practice exclusively through digital platforms. Content Cage opens the exhibition X with the kind of unsubtle theatricality that capitalism loves: a woman, crawling, tethered, lit like a product. The performance draws a clean, grotesque parallel between two factories of femininity: the industrial milking facility and the influencer farm. One squeezes out milk, the other metadata. Both want yield. Both want the body. Preferably filtered, feminized, and on schedule. Capitánis clad in a translucent white skinsuit, hoof-like boots, and a slicked-back ponytail. A massive cowbell hangs from her neck like a cruel joke or a corporate ID. She enters from outside the gallery, crawling slowly behind a caricature of a man: a hyper-masculine, agro-pornographic farmer dragging her by nothing but performance and implication. The choreography is minimal, degraded, and each step is a lagging upload. The reference to Bruce Nauman’s Double Steel Cage Piece (1974) is deliberate but mutated. Here, the architecture is a single cage designed in collaboration with Daryan Knoblauch; brutalist, gridded, industrial, and mounted on wheels. Mobility masquerading as freedom, one might say. There’s no escape, only circulation. The cage moves, but the structure stays the same. Optimization rolls forward. As André Lepecki notes, Bruce Nauman was never exactly considered a ‘proper’ dancer, nor did he claim to be a choreographer. Still, his work persistently engages with choreographic modes, not despite, but precisely through his outsider position. Nauman’s experiments allow choreography to be understood outside its usual disciplinary confinements, opening up space to consider how modernity itself invests in a strangely overactive, restless body. Approaching the choreographic beyond the formal limits of dance doesn’t dilute dance studies; it stretches it. It invites a rethinking of how bodies, subjectivities, and political structures move and are moved, across mediums and institutional frames.[1] Much like Nauman’s experiments with physical entrapment and the poetics of restriction, Capitán’s choreographies dislocate the body from its assumed legibility. Capitán, too, urges us to reconsider the choreographed body, not just as something that moves, but as something moved, regulated, and exposed. Her performances operate as quiet ruptures, unsettling the institutional scripts that dictate where bodies belong, how they behave, and who gets to watch them. This becomes glaringly apparent in Content Cage, and just as insistently in Solos y conectados and SOLAS; three choreographies orbiting a shared nucleus: entrapment, fixation, the slow violence of being seen. There’s a twitchy obsession with being pinned, by gaze, architecture, and the dull ache of perception itself. Entrapment isn’t simply a condition here; it’s the method, the choreography, the atmosphere.

OT: Your work seems to contain this fascinating tension between collectivity and individuality. For instance, when I watch your performances, often through Instagram or YouTube, I get the sense that the dancers are moving as one unified body. Yet their individual identities are still somehow palpable. Is that something you’re intentionally working with?

CC: Absolutely. That tension is very much at the core of what I do. I’ve long been interested in how distinct identities can exist within uniform or even mechanical structures. In earlier works like Solas y Conectadas, I was really focused on making those individual identities visible through repetitive, mechanical movement. But over time I started to question whether that kind of visibility was sustainable or even possible at all. What tends to happen is that the performers gradually lose their individuality. They become almost like machines. And in that process, something strange starts to surface, a kind of eerie, hyperhuman presence. It’s not just dehumanizing. It reflects the way we ourselves begin to act when constantly watched, tracked, and repeated in digital systems. The body doesn’t disappear. It becomes a signal, a loop, a pattern.

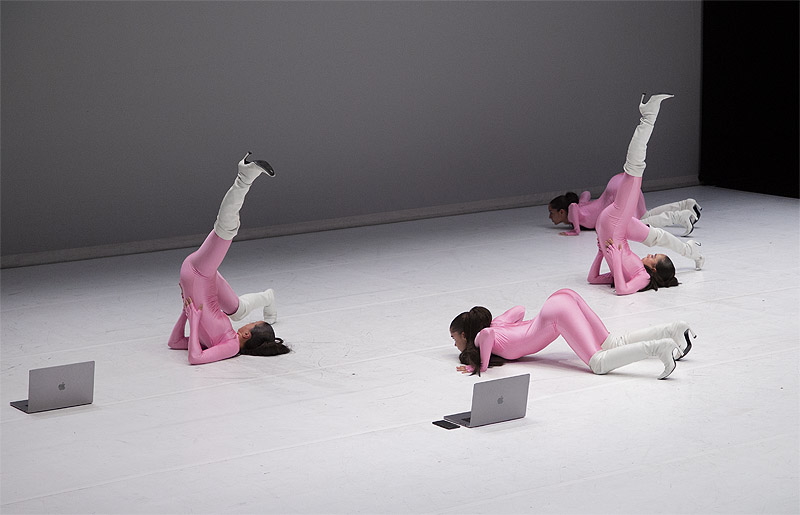

American scholar Shoshana Zuboff introduces the concept of surveillance capitalism, describing it as a new economic order that appropriates human experience as raw material for covert processes of data extraction, behavioral prediction, and commercial profit. Rather than critiquing this system from an external position, Capitánengages with its structures and agents directly. Her work operates from within the surveillance capitalist framework, using its own logic and aesthetic to reflect, distort, and expose its underlying mechanisms. As Zuboff outlines, the surveillance capitalist framework constitutes a parasitic economic logic –one that no longer prioritizes the production of goods or services, but instead organizes itself around a global infrastructure of behavioral modification. Human experience becomes the raw material, harvested and repurposed through opaque systems of extraction, prediction, and commercial exploitation. Within this architecture, the subject is not merely observed but continuously shaped. In Capitán’s choreographic practice, this dynamic is neither resisted nor romanticized. Instead, she performs it, amplifies it, rendering the mechanisms of control hypervisible by miming their aesthetics, gestures, and affective rhythms.[2] The performances peel back the slick surface of the networked form, revealing connection not as some benevolent force of inclusivity or democratized wisdom, but as a seductively engineered myth. What’s laid bare is the choreography of control; connection as currency, as surveillance, as a mechanism dressed up in the language of care while quietly calibrating bodies, desires, and attention. Capitán’s 2023 performance SOLAS accompanied by a soundtrack by Slim Soledad exemplifies this choreography of control, staging bodies, desire, and attention as both spectacle and system. Sixteen women in identical pink bodysuits, thigh-high white boots, and slicked-back ponytails perform in front of glowing MacBooks, crawling, twerking, and seducing their own reflections in the webcam lens, operating like a large pink organism. The visual language is unmistakable: Chaturbate, camgirl culture, the erotic feedback loop of digital labor. But this is not just mimicry. Capitánweaponizes the codes of hyperconnectivity and hyperindividualism, rendering them strange and hypervisible. The performance does not simply reproduce the aesthetics of platformed eroticism; it interrogates them. What appears as empowerment collapses into a ritual of submission, a feedback loop where agency flickers and vanishes beneath the glow of monetized attention. Surveillance is not lurking in the background. It is the architecture, the stage, the invisible audience pressing its face against the glass. At the same time, the audience is tethered to the performers through a digital umbilical cord, each viewer complicit in the loop. The performers’ identical bodies, pink, polished, perfectly choreographed, don’t just echo one another. They dissolve into a single pulsating commodity, exposing the eerie transparency of the female form in the data economy. Here, the body is both hypervisible and nowhere, flattened into pure signal, a fetish object drifting through a marketplace where desire is harvested, coded, and sold before it even finishes forming.

OT: I’ve thought a lot about SOLAS. It feels like there’s a double layer to it, all these women performing toward the screen, but at the same time we, as viewers, are also watching them. Could you talk about your intentions behind that piece?

CC: There are multiple ways to approach that work. One layer is a reflection on algorithms and how our generation is shaped by them. I like to speak about my generation: we’re increasingly becoming homogenous, not just in the way we dress, but also in how we perceive the world. Algorithms only show us what we already want to see. In SOLAS, the performers begin by enacting different figures, there are seventeen choreographic structures in total. But over time, around ten minutes in, they begin to move in unison. They become almost indistinguishable, like machines. That’s why they’re all dressed in identical pink. Though the choreography is different at first, they end up synchronized, visually and mechanically.

OT: So it’s about both individuality and erasure?

CC: Exactly. It’s also about the commodification of female bodies on digital platforms. Each performer is connected to a separate pornographic livestream. When the audience enters the space, they receive a unique QR code that links them to a specific performer. Each audience member watches only one dancer.

OT: So, does it become a kind of individualized show for each viewer?

CC: Yes. Midway through the performance, there’s an interactive element, a game involving a box and a ball. The performers speak directly to the viewers, who must guess where the ball is. But here’s the twist: I switch the performer in front of the screen without the viewer noticing. The idea is that it doesn’t matter which woman is being watched; what matters is simply that there is a woman being watched. It’s about the consumability of the female body. The performance leads the viewer to a live erotic site, without explicitly revealing that it is one.

OT: So it’s a kind of unconscious consumption, audiences don’t even realize what they’re participating in.

CC: They’re consuming without knowing. That’s the deeper critique. We often think we’re in control of our consumption, but we’re not. The algorithm dictates what we see, and we engage with it uncritically.

The illusion of autonomy in consumption, the idea that we choose freely, that we remain in control, is precisely what Capitán’s work exposes as deeply manufactured. Her performances do not simply illustrate desire; they anatomize the infrastructural conditions that produce, circulate, and capitalize on it. At their core is a sustained interrogation of surveillance capitalism, not as a backdrop or theme but as a totalizing condition. This is an economy that no longer depends on the production of goods but on the systematic extraction of human experience, transforming attention, emotion, and gesture into behavioral surplus. It is not an accessory to life. It is its operating system.

In Content Cage, Capitán resists the comfort of metaphor. The piece does not simulate surveillance. It enacts it. Mounted inside the cage, an iPhone streams her movements directly to Instagram, collapsing the space between performer and platform, body and broadcast. The choreography is meticulously self-aware, saturated with references to camgirl aesthetics and the labor of constant visibility. Yet the work resists flattening into parody or critique. Instead, it embodies the very logic it seeks to expose. Glitches in the stream become aesthetic ruptures, momentarily disrupting the flow of capture without ever undermining its hold. Surveillance here is not a visual motif. It is the frame itself, the structuring logic through which performance, perception, and value cohere. Rather than offer resistance, Capitán’s work suggests the futility of such gestures within a system that thrives on exposure. Her choreography stages complicity, not escape. Echoing Marx’s image of capitalism as a vampire that feeds on labor, this contemporary configuration marks a shift, one in which labor is no longer confined to production but extends into every facet of embodied life. In this framework, the subject is not merely visible. They are metabolized.

Seeing the body as something porous and in flux is hardly a revelation. Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze, and Guattari have all, in their own ways, sketched out a body that is never fixed but always in motion, politically, socially, and psychically. Their writings don’t just describe the body but reframe it as a site where new forms of power and control take hold, where submission and resistance co-exist, where something else, something not yet named, is always on the verge of arriving. Breaking with the modernist insistence that dance must unfold in a seamless continuum of movement opens up a rethinking of how dance comes into presence. Presence here no longer refers solely to the dancer’s ability to balance technical precision with expressive intent; it’s something messier, more charged. If choreography once arose in early modernity to rework the body into something that could present itself as a whole being oriented toward movement, then perhaps the current fatigue with dance as smooth, continuous motion is not just aesthetic burnout but part of a broader resistance.[3] A soft rebellion against the idea that subjectivity must be shaped through flow, that existence itself depends on unbroken movement. Drawing on Lepecki, one might say that Capitán’smovement practice refuses the fantasy of the autonomous body. Instead, the body is rendered as a porous system, leaky, reactive, exposed, producing not only modes of discipline and control, but also resistance, friction, and strange little becomings. Movement becomes less about execution and more about negotiation: between forces, affects, and the choreography of power itself.[4]

CC: Another layer of SOLAS is its design for virality. I allow and even encourage the audience to take photos and videos during the performance. They’re not only witnessing the work, they’re disseminating it in real time. I find this fascinating. Audiences today are not passive; they are active participants in the life of the artwork. Art is no longer confined to a space or a moment. It is everywhere: fragmented, shared, and reshaped. Particularly among younger audiences, there is a sense that art belongs to them, that it should be visible and engaged with constantly.

Capitán’s Solos y Conectados premiered at the Staatstheater in Kassel as part of the opening program for the 15th edition of Documenta. The piece stages six performers dangling inverted from harnesses and chains, their bodies encased in sterile white bodysuits, suspended from a rotating steel rig that evokes both playground equipment and surgical apparatus. The choreography oscillates between enforced unity and disembodied solitude, each body linked to the next by design yet isolated in its own orbit of restraint. It is a brutal geometry. As with her earlier works, the scale is intimate, almost forensic, prying at the edges of embodiment. Dance is not so much performed as dissected. The piece leaks an unmistakable anxiety about the technosocial, hyperconnected and still somehow irreparably alone. What Capitánmakes clear, painfully clinically clear, is that to be tethered is not the same as to be touched.

Don Ihde writes about the body as something not just lived but mediated, recalibrated through the quiet coercions of technology. He distinguishes between two bodies. Body One is the body you forget you have. The body through which you move, not the one you watch. It is the phenomenological body, the flicker of balance when you walk, the soft blur of vision behind eyeglasses, unregistered but utterly foundational. It is the transparent body, the one that recedes from consciousness precisely because it works. Then there is Body Two, the body as spectacle. The body seen, surveilled, and edited. Not lived in, but looked at. It is sculpted by filters, by avatars, by aesthetic regimes. It performs itself in mirrors, on feeds, under lights.

In Solos y Conectadaos, these two bodies collapse into one another. The performers hang upside down, suspended in white suits from a cold carousel of metal, bodies straining, trembling, enduring. The audience cannot help but feel their muscle tension and their breath. This is Body One, raw, visceral, undeniable. And yet, these same bodies are calibrated into a choreography of exposure, uniform, distant, meticulously framed by the architecture that binds them. This is Body Two, aestheticized, abstracted, held in place. Together they form a diagram of the contemporary condition, connected, yes, but each alone in her orbit, turning quietly inside a machine.[5]

OT: For those unfamiliar with your work, those who haven’t seen your performances or know your background, is there something essential you’d want them to understand? A central message or theme that drives your practice?

CC: I wouldn’t say there’s one central message, but I do find myself returning to the same core ideas. If you watch Solos y Conectados—or any of my works—there are always new layers. But beneath it all, I’m talking about how we live within a machine. A system that perpetuates itself. My work explores how we’re trapped in cycles, and I often use what I call ’pacifiers’ in my choreography—devices or elements that metaphorically sedate or distract the performers. They’re symbolic of the way society distracts us from the systems that govern our lives. We’re constantly being soothed into complacency. I suppose I don’t have a singular, declarative message in my work. I’m not interested in using performance to convey a fixed opinion. Rather, I aim to present the texture of contemporary life, to expose its contradictions, discomforts, and distractions. I rarely explain my work in literal terms because I don’t want to dictate how others should interpret it. My goal is to create spaces of ambiguity where viewers can draw their own conclusions. The performance is structured in four chapters, each exploring a different relationship to systemic control. It’s not just about being digitally connected—it’s about how we relate to the larger system. The work is about how we fight against the system, how we learn to live within it, or how we don’t even realize we’re being controlled by it.

OT: So the system is almost invisible, something we’re immersed in without even knowing?

CC: Yes. In the piece, the system is symbolized by a large carousel structure. The performers enter it without understanding how it works. It’s seductive: it looks like a game. But slowly they realize it’s a machine, and the fun turns into something oppressive. The carousel represents capitalism, neoliberalism, and this illusion of choice and pleasure that actually controls us. I use machine-like materials on purpose; large, heavy, metallic structures. They have a kind of clinical, sci-fi aesthetic. My work is very much rooted in a vision of the future, in speculative fiction. I’m interested in how these machines interact with human bodies—how fragile we become in comparison. In Solos y Conectados, the machines are so large that when the performers try to resist them, they can’t stop them. The machines are too powerful. I think the point is that the performers come to understand that it’s impossible to stop the machine alone. Only when they are together are they able to halt it. What interests me is how these large mechanical structures interact with the human body, how their scale and force overwhelm individual resistance.

OT: That really resonates. I was also wondering about how you perceive the body in relation to these systems. Do you think of the body as a machine? Or do you see the human and machine as distinct entities?

CC: It’s less about the body being a machine and more about how we are becoming machine-like. My interest lies more in the reciprocal transformation, how we are becoming machines and, simultaneously, how machines are becoming more human. I’m concerned with how we coexist with these technologies.

Candela Capitán’s choreographic practice emerges at the intersection of feminist cyberpunk, posthuman critique, and the aesthetics of exposure, staging the body not as a site of resistance but as a conduit through which systems of control are both enacted and made visible. Her work resists moral binaries and tidy resolutions; instead it presents hybrid figures, neither fully human nor fully machine, neither victim nor agent, that embody the contradictions of our networked condition. Within her performances, the body becomes a signal, endlessly calibrated by surveillance capitalism yet never entirely consumed by it. In this porous, machinic terrain, Capitán stages not rebellion, but ambiguity, a feedback loop of desire and discipline that compels viewers to confront their complicity. Her feminist, digitally tethered dramaturgies do not offer an exit from the machine. Rather, they diagram its operations, inviting us to feel the weight of its choreography, to trace its logics across flesh, screen, and infrastructure.

Bibliography

Lepecki, André. Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement. New York London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2006.

Ihde, Don. Bodies in Technology. University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. First trade paperback edition. New York, NY: PublicAffairs, 2020.

[1] André Lepecki, Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement (New York London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2006). 5

[2] Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, First trade paperback edition (New York, NY: PublicAffairs, 2020). 17

[3] Lepecki, Exhausting Dance.7

[4] Ibid. 5

[5] Don Ihde, Bodies in Technology, Nachdr., Electronic Mediations 5 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). Xi-xx