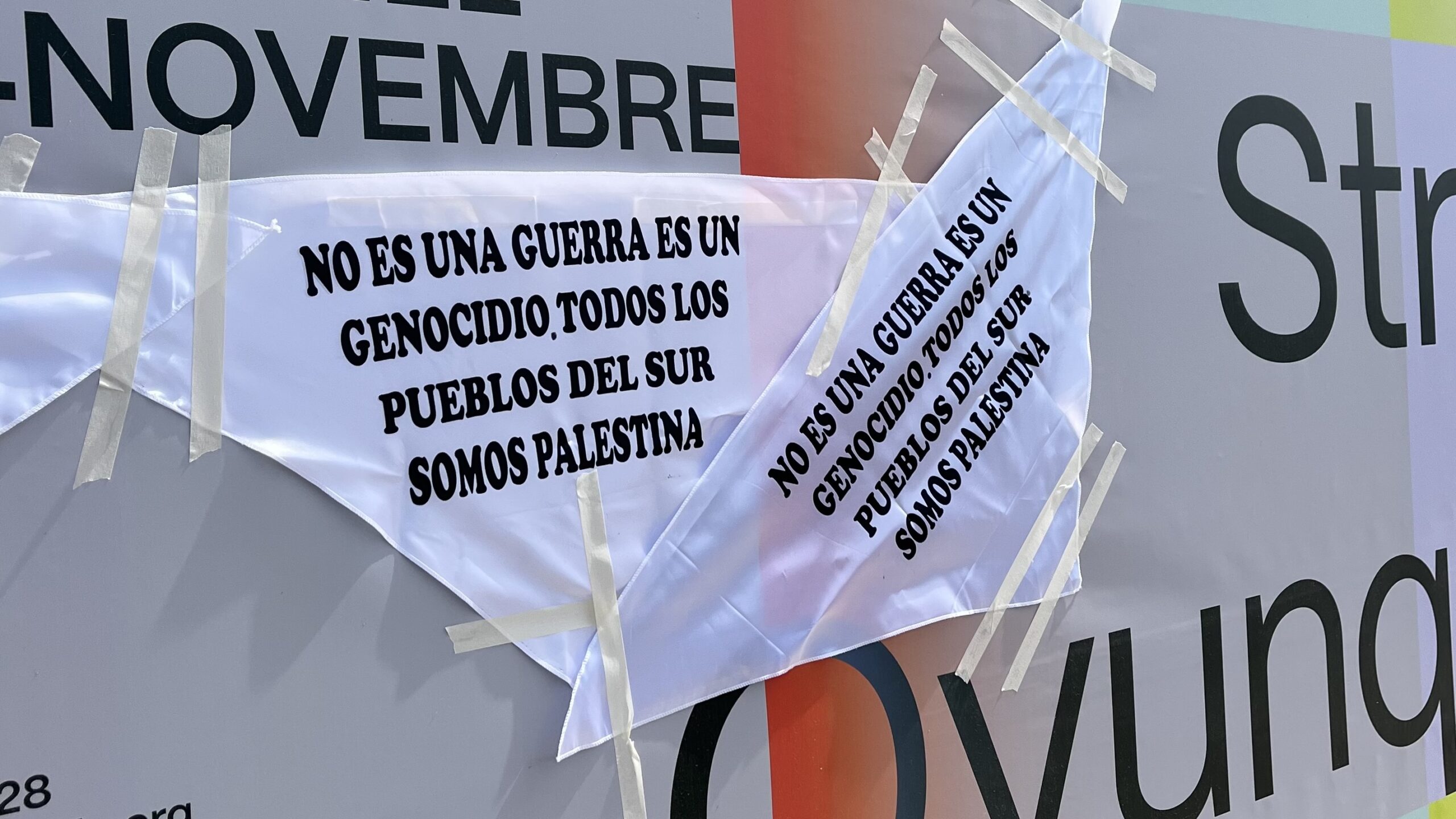

At a random bar next to the busy San Marco square, I handed over an ‘ANGA’-pin, (Art Not Genocide Alliance) to two French women. The ongoing genocide in Gaza had spurred artists and art workers to organize a protest and boycott of the participation of the Israeli pavilion and its’ accomplices. Like Eurovision, despite massive protest, they had been granted permission to open their pavilion to the public. (Unlike Russia that were excluded in 2022.) As I was handing over the Palestine-colored pins we started talking about the main exhibition of the 60th Venice biennale. São Paulo-based curator Adriano Poderosa’s Foreigners Everywhere. One of the french women said “I felt like I was walking through a colonial exhibit. Like those of the French empire”. Usually, I wouldn’t heed the opinion of the French people, when it comes to critique of colonialism, but this woman for one had asked for an ANGA-pin, and the second she was black. Her racialized experience in a country approaching fascism made her words more impactful to me. It could literally have been her great-grandparents being exhibited in the West African style villages on the streets of the 1889 Universal Fair in Paris.

How is decoloniality articulated? When is it successful? The title of the 60th Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere comes from the name of a Turin collective who fought racism and xenophobia in Italy in the early 2000s. The intention of Adriano Pedrosa seems to have been an exploration of the ‘other’. Pedrosa specifically highlights the queer artists, the outsider artists, the folk artists and the indigenous artists as points of departure for the exhibition. With intentions I highly respect and align myself with, there was a sour aftertaste in the exhibitions admirable decolonial ambition. Many I talked to, including myself, felt odd about the main exhibition. My trouble was obviously not that of the representation of artists from the global south or other underrepresented communities, myself belonging to a sliver of a fraction of such a lived reality. I only have sympathy for that cause. But when walking through the main exhibition space I was stunned over the amount of art works that seemed to represent a more or less stereotypical idea of whatever culture the artist belonged to. It felt like the artists were only invited on basis of their social position, not their artistic practice. What gnaws me is that Pedrosa did two things simultaneously through this. He gathered a vast amount of less represented artist to a global stage, who’s works and careers hopefully will flourish. But he also managed to, unfortunately, re-iterate one of colonialisms major codes of conduct, the fascination of and distance to ‘the other’. I was left with the feeling of having looked at ‘the other’, not with or from within.

But as with every hypothesis and take, there are fundamental contradictions to my arguments. There were of course many artists and artworks that eluded being gazed at and managed to work with the poetry of auto-mythology in stunning, inviting and convincing ways. I will write about two performances that beautifully managed to discuss self-creation and/or reflection on their own terms. The two artists are Lap-See Lam and Ahmed Umar.

GENDER CREATIVE POISE (CHAPTER 3)

Ahmed Umar’s piece Talitin (arabic for third) is a dance piece and video work that queers bridal customs of the artist’s native Sudan. In the video work we follow Umar dancing in a Sudanese bridal costume. The artist is embodying dances that were denied to him as a child, since after puberty he was rejected to partake in these rites. The dances are subtly joyful, full of precise hand gestures and brilliant use of costume. Umar dances to mesmerizing choral folk songs which I can’t understand the lyrics of however literal understanding is not needed for me to enjoy the queer and somatically expansive act of performing gender creativity. By bending and ignoring social norms of Umar’s native Sudan, he turns his own body into a cultural spectacle of possibilities. It is simultaneously a reckoning of the repression faced by Queer individuals in Sudan (having removed capital punishment for same-sex activities only in 2020) at the same time as it articulates another queer situatedness: Talitin, the third.

It is a social position I don’t have detailed awareness about but from what I gather from reading about the artist online, performing this rite is a dangerous act for Umar. I’m reminded of similar acts of gender non-conformity and the fact that they are a constant to all human societies. As illustrated in Joan Roughgarden’s book Evolution’s Rainbow (to name just one source), playfully engaging with codes of gender expression are more rule than an exception in human societies, and the natural world for that matter. I am not aware of Sudan’s specific gender-diverse history but it is a well-known fact, that the fanatical western hegemonic gender-binary usually didn’t exist in pre-colonized cultures. From my perspective, Tatilin, then join the ranks of many gender expressionists across time and geographies, but also specifically performs and reimagines a local Sudanese genderbending. I imagine that for a Sudanese person, it carries a culturally specific weight I can’t even begin to fathom.

OPERATION OPERA: FIGURING HOME

Spread over one day, I witnessed the three acts of Lap-See Lam’s performance The Altersea Opera in the Nordic Pavilion. The actual exhibition consisted of Kholod Hawash’s costumes made for the opera, a filmed version of the live work and giant bamboo scaffolding that spread outside the walls of the pavilion to a giant dragon head and tail on either side. Just as the title hints at, the permanent exhibition was centered around a live opera performance with several singers and musicians performing live. The opera follows the half-fish, half-man Lo-Ting, a creature from Hong Kong folklore, as he, together with his crew, sails back home toward the Fragrant City.

The Altersea Opera moves form western waters throughout continental oceans where Lo-Ting frightens and enlightens the character’s he meets along the way. The character of Lo-Ting (past and future) serves as a vessel to explore the artists own experience with displacement and belonging. Growing up with Cantonese parents in a white Swedish context, Lap-See Lam has a specific set of experiences and knowledge of which the performance explores. From discussions with friends and family belonging to the global majority, in a white Nordic context, I’m aware of the creeping feeling of alienation being an ethnic minority can produce. Tze Yeung Ho’s musical composition, the backbone of the Opera, manages to make this alienation audible. Through a strange and fantastic array of musical instruments to the way they are being played in, I am constantly stimulated but never really at ease.

The mythological character of the words being uttered, the thrilling trills of the wind instruments and the returning narrative of aquatic states makes The Altersea Opera an intriguing tableau to sit with. It is mostly narrated by the brilliant performer Ivan Cheng (Future Lo-Ting), that manages to keep the audience engaged even though the architecture of the pavilion makes it hard to always see and hear. What this multilingual and multiethnic opera manages to convey in the very least, is a very broad and real idea of what being Nordic is. In the Nordic countries racism has a particularly sinister quality of a pre-figured Scandinavian humanitas, that thinks of itself as benevolent, even when pursuing some of the strictest migration policies in Europe. Belonging to the global majority in this context of supposed benevolence means that one often must find one’s own strategies to survive. My thoughts go to Adam & Amina Seid Tahir’s work several attempts at braiding my way home which thematically belong to the same project. That of using artistic practice to navigate the tension between belonging and displacement. Adam & Amina’s work, like The Altersea Opera, manages to not only navigate the tension but use performance to aesthetically and experimentally carve out their own living space. Being first and foremost a reflective surface for people of similar lived experience, it also serves someone like me, a white Scandinavian viewer with sensorial and qualitative clues to both empathize with the experience as well as consider where I’m positioned in that dynamic.

There is an ethno-nationalist specter spooking about the majority of western institutions. The Venice Biennale being one of these. The Altersea Opera not only hints at simplistic mechanisms of nationalism but manages to describe with aesthetic sincerity and poise the qualitative experience of belonging to many places, cultures and even times, at once.

DOES THE MARKET REIGNS SUPREME?

There was a decolonial critique of the nation-state throughout many of the national pavilions. This year at least the Brazilian, Australian, American, Bolivian and Danish all curated indigenous artists. The pavilions consisted of video works of indigenous lifestyles (Brazil), harrowing monuments of grief and loss (Australia) and photography of everyday life from Kalaallit Nunaat. There was a wide array of indigenous voices that used rather different artistic disciplines, discourses and methodologies. Although I was impressed with the sudden burst in representation, most likely following the popularity of the Sámi pavilion at the last biennale, there were several questions haunting me; Does presenting a critique of one’s own nation-state simply become a currency to affirm said nation-states as benevolent? Or does piratical intentions of artists and curators become a way to use soft power to rock the stability of such states? It is always hard to measure the geo-political implications of artistic practice until people backed by the powers of political institutions speak their name.

Finally, I sit with a strange feeling after having visited this year’s biennale. As mentioned above there were several highlights that illuminate decolonial trajectories in artistic and curatorial practice that I’m excited to follow. But you can never make a chicken out of a wolf. The Venice biennale is one of, if not the, primary sites of the art market. With an emphasis on market. There is obscene wealth present in the exhibition rooms and around the biennale. Gulf state princesses invite old money Europeans to mingle on their yachts while gallerists come to check out the latest trend they can capitalize on. In a double-bond between capital and culture so familiar to the visual arts scene, yet it still remains bizarre to me as a dance artist. Adriano Poderosas intention to shift the attention to the global south is successful, but the geo-political reality of Israels continuing genocidal efforts in Gaza and Western states continued support for this campaign haunts the whole event, and rightfully so. There is a fundamental hypocrisy in centering decoloniality in the gallery but not practicing it in the organization. A cultural boycott of a state under genocidal investigation by the ICJ should not be considered controversial. But as the biennale chose not to act, it shows where its’ actual priorities lie. That the art market more often, than not serves capital, and not culture. Although I joyfully imagine that this Venice Biennale is a scathing nail in the eye of Giorgia Meloni and her accomplices, I couldn’t help but wonder, who is this spectacle for?