– Notes on a neomedieval summer in early second millennium

It’s a quiet Sunday. The sun warms my skin over a landscape that could have stepped from a Hesse novel: a red-painted barn on an island in the Danish archipelago, once ruled by sugar beet factories, now inhabited by artists who drifted in after the post-industrial exodus. Amid the calm, GOD HUMAN ANIMAL MACHINE unfolds as a summer 2025 exhibition probing existential observations on the relationships between technology, life, and its in-between liminal spaces. Curated by the collective South into North (Francesca Astesani and Julia Rodrigues) at 44 MOEN, the show became my starting point for tracing the many variations of this theme I encountered over the summer, pushing me to wonder: is contemporary art turning to medieval imaginary not to revive the past, but to wrest the story back from the grip of techno-feudalism?

The pastoral frame, faux solarpunk as mise-en-scène, might read as idyllic, but bristles with metaphysical tension. Once imagined as a techno-free Eden, the countryside pulses with the same logics as the city. Wi-Fi and divine signals alike flicker and vanish, spectral and elusive, coursing along identical circuits of production, extraction, and control. Idyllicity is a veneer: under it, the sacred and the technological are inseparable, equally instrumental, equally surveilled.

The title inevitably summons Meghan O’Gieblyn’s essay, where a pet robot becomes a lens for theological inquiry. She traces how metaphors migrate between religion and technology—how machines inherit our eschatologies, and in their quiet insistence, reveal something about ourselves. The exhibition works in the same register: not to reconcile the divine and the digital, but to expose the loops by which each becomes the other’s metaphor.

Words carry insurgent force. Anima—breath, the current that fills lungs, stirs leaves, animates flesh. Animus—spirit, mind, intention; the force driving that breath, the engine of motion. In Greek, psyche is air in motion, a fragile wingbeat departing the body at death. Language and life circulate between the corporeal and the immaterial, caught in circulation like code, like prayer, like myth rewritten in motion.Between anima and animus lies the tension of existence: the breath that sustains, the will that commands. Once hierarchies ruled—man over beast, spirit over body, mind over matter, machine beneath all—but those orders now dissolve. Breath, soul, algorithm, flesh: each asserts its alterity. Reconsidering these forces is to rethink kinship and relationality. The human is no longer the fixed center; the sacred and the digital are caught in motion together, inseparable and unstable.

Yet three hundred years after the Valladolid debates, the West remains locked in conversation with itself. It circles endlessly around the question of what counts as animated beyond its own image—whether other people, animals, or now, machines. In the mythos of Silicon Valley, AI is not just software but a new God—at least in fantasy. The language of tech drips with theology, Christian metaphors rebooted as marketing copy. Beneath this vocabulary lie ultra-conservative prerogatives: the Thiels and Musks of the world invoke the collapse of religious moral values to explain falling birth rates. Might this so-called spiritual crisis, then, be inseparable from a deeper cultural fixation on control—one that manifests as much in the governance of life and death as in the technological imaginary?

Aria Dean’s Abattoir, U.S.A! (2023), encountered in the first gallery, recasts the slaughterhouse as a spectral mirror of capitalism. Empty pens in a ghostly warehouse implicate the viewer in systems of violence that link the exploitation of animals, the commodification of Black life, and the logic of profit. Death is everywhere yet nowhere, a haunting rhythm of Afropessimism and industrial modernity, an allegory of an institution that “educate[s] men in the practice of violence and cruelty” according Dean.For the two curators, the medieval-technological link in the show is less history than romance. It’s a projection of lost intimacy between spirit and machine. In the Middle Ages, animals fueled myth, imagination, and spiritual inquiry, as reminded in Edith Karlson’s Vox Populi (2016–2025). Creatures become vectors of interconnectedness, her philosophy unflinching: “Every shit is related to the shit that follows and forms one continuous strand of shit that no one can avoid.” I guess Karlson’s take is the Western’s equivalent of Indra’s Net.

For former Greek minister Yanis Varoufakis, our times aren’t ones of progress but regression: the so-called future has already collapsed into a dystopian cyber-take on the Middle Ages. Capitalism hasn’t ended, he argues, it’s mutated into what he reactualized as techno-feudalism, a term first coined by French economist Cédric Durand, understood as a post-y2k version of serfdom where we kneel not before lords but before hoodie-clad vassals of Big Tech. In this light, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Reba Maybury, and Joanne Robertson’s Day of Wrath (2020) skewers incel culture and fragile masculinity through the figure of the witch, dredging up the pornographic demonology that circulated during the 13th-century witch trials. Their work suggests that the specters of medieval persecution return not as distant history, but as distorted reflections in the faces of today’s digital overlords.

Most of what we think we know about the ‘Dark Ages’ is itself a hangover from Enlightenment myth-making anyway. A few weeks after the show, I found myself at the Feminist Library in London and randomly grabbed Susan Mosher Stuard’s Women in Medieval Society. For Stuard, there’s evidence that early medieval women ran estates, held land, practiced abortion and birth control via herbalism, led monasteries, and acted as spiritual authorities on the contrary to modern belief. Their erasure came later, around the first millennium, when church reforms closed down female power in religion and the rise of towns and guilds cemented male control over economic life. This is not about idealizing this period in time, but about illuminating the mechanisms of systemic exclusion from public life—mechanisms that may have marked the beginning of a broader strategy of hierarchy and subjugation of the “Other,” one that would only intensify and spread to most beings in the centuries to come.

Stuard’s claim made me wonder about our own millennial shift. The eleventh century’s ‘take-off’ marked the start of a darker turn. Today, our technological acceleration follows the same pattern. Social media and AI surge forward, dazzling on the surface, yet quietly narrowing the spaces where other forms of agency once thrived—trapped under surveillance and algorithmic control. “Cloud capital has shattered the individual into fragments of data, an identity comprised of choices as expressed by clicks, which its algorithms are able to manipulate. It has produced individuals who are not so much possessive as possessed, or rather persons incapable of being self-possessed. (…) No, our focus has been stolen. And because technofeudalism’s algorithms are known to reinforce patriarchy, stereotypes and pre-existing oppressions, those who are most vulnerable – girls, the mentally ill, the marginalised and, yes, the poor – suffer the outcome most” reminds Varoufakis in the last chapters of Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism.

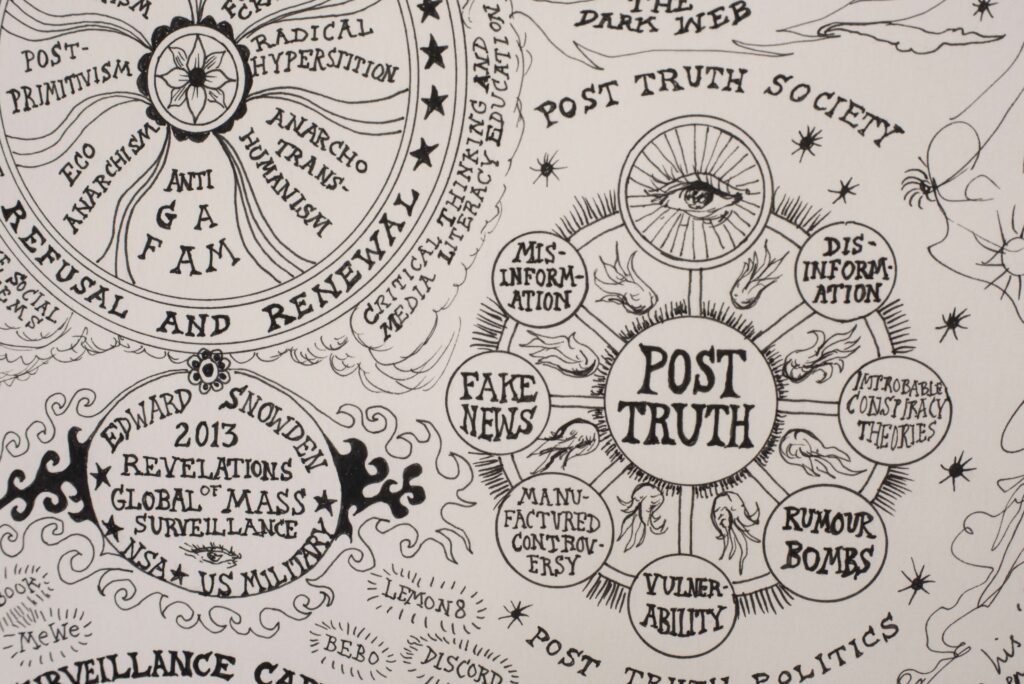

Meanwhile, artists like Mark Leckey search for cracks in this narrative, diving into Europe’s tortuous past to see if somewhere in the ruins we can still locate a collective soul. In Me into The Wilderness (2022), Leckey mobilizes Byzantine iconography and medieval metaphysics as conceptual tools for apprehending life amid capitalist crisis, displacing any impulse toward the revival of belief. For Leckey, the mystery once projected onto God now rhymes with the excess and disorientation of our own moment. Perhaps he has a point. Perhaps this inquiry into old rites, rituals and beliefs might be the key to a sincere connection to the sacred. The sacred being, a way of moving, making kin, caring, seeing, feeling, being with ourselves and with others—whether animated with soul or not. A notion of precious that defies the commodification of all things. Something British artist Suzanne Treister caught on in her well-commented HEXEN 5.0 (2022-2025) series.

Our fascination with machines arrives belatedly and in the wrong place—certainly not where Silicon Valley would have us believe. After all, robots were imagined outside Europe long before its mechanical age. To the medieval world they were indistinguishable from magic: automata that moved of their own accord, angels of brass and whirring saints. Both alchemy and machinery in fact trace their origins to Baghdad, where engineers and philosophers developed intricate water-clocks, automata, and chemical practices that fused experiment with speculation. From there, they entered Europe not as neutral tools but as diplomatic gifts.

In the Islamic world, science, technology, and the occult were never so neatly separated. Al-kīmiyāʾ, alchemy, was both metalwork and self-transformation, material practice entwined with spiritual discipline. Machines and ritual, invention and enchantment, were inseparable. What we now call “technology” was an affair of spirits, symbols, and power. Hong-Kong born philosopher Yuk Hui makes a similar point: Western frameworks flatten technological thought, ignoring traditions, like Daoist philosophy, that approach technology through harmony rather than mechanics.

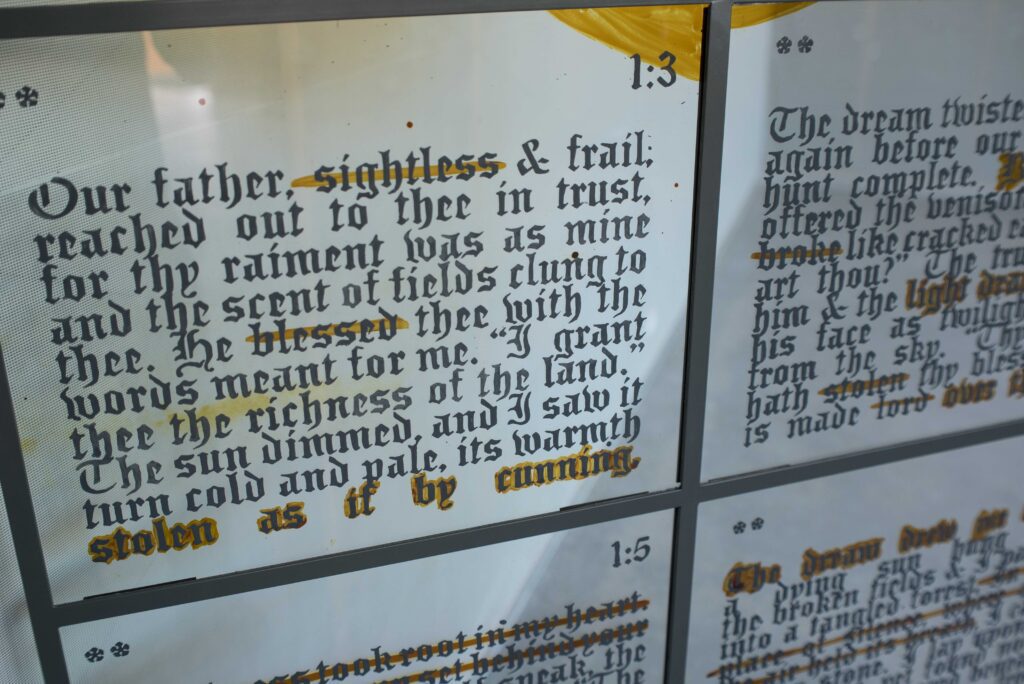

That might be the point artists Sophia Al-Maria and Lydia Ourahmane ironise over in A Blessing and A Betrayal (2024). Their stained-glass diptych reimagines the story of Esau and Jacob (Genesis 28) with an insurgent, almost blasphemous twist: medieval craftsmanship fused with AI-generated “scriptural” fragments, inscribed in gothic blackletter and mock marginalia. The authority of sacred text falls into algorithmic noise, laying bare a simple truth: myth, whether biblical, national, divine, or digital, is no longer a vessel of divine permanence but a site of unstable rewriting. Here the sacred machinery of English national myth-making quietly unravels under the gaze of two immigrants. I just couldn’t stop thinking about the genius of this work, when that same weekend I stumbled on Stuard’s book in London I randomly found myself in the midst of the UK’s biggest fascist protest since WWII. Interesting time to be alive.

I guess belated artists’ engagement with medieval imagery reads less as retrospective longing than as a reckoning with the logics of our contemporary tech lord-dom. The “reenchantment of the world” that philosopher Byung-Chul Han yarns for, might then find resonance in culturally informed and localized rites and rituals rather than exported neocolonized spiritualities. Pre-patriarchal rites, pagan traditions, and traces of medieval mysticism become in this context instruments for critical excavation.

One must keep in mind though, that this very act of “enchanting recovery” of old collective memory would be vain without a systematic surveying and meticulous dismantling of what has hardened it into hegemony, codification, and violence. Only through this dual movement can anything genuine be preserved, can anything be reclaimed.