On a bright autumn afternoon Dr. Lucy Fair met with Galerie to discuss the economy behind their gallery operation.

Calmly seated by one of the animated terraces of cours St Louis in Marseille the two representatives of the immaterial gallery for immaterial artworks wore elegant summery Herr von Eden suits in blue linen and grey wool over surfer Miami tee-shirts.

The conversation was transcribed by Dr. Lucy Fair and its production was supported by Sub text labour

Dr. Lucy Fair:

First, could you tell me why; why did you start an “immaterial” gallery for “immaterial”

artworks?

Galerie:

Galerie is a polymorphic entity, mobilized by a multiplicity of drives and needs. One of the initial reasons was that artists around us were making extraordinary and important artworks in unconventional mediums, such as a joke, conflict or companionship. We wanted to find ways to center these works in an art market that was and still is very much geared to more traditional mediums. And we wondered how they in turn could change that art market. We chose artworks that we loved, and like all good loves they were also the ones who could produce trouble for us. The ones we couldn’t have imagined in advance how to sell or represent.

Dr. Lucy Fair:

You are not the first ones to promote unconventional artworks in the art field… Your approach has a certain history, wherein avant-gardes end up feeding the forging of new aesthetic canons and the notion of radicality and newness become a vector of value to generate market opportunities. I am thinking about how the post-Fordist turn and service economy enabled the emergence of conceptual art practices. The current experience economy is obviously a fertile ground for performance and event-based works. I see galleries, art fairs and dealers already involved in this transition.

G:

Yes – These are very exciting problems and luckily we are not alone in trying to deal with them 😉 We could mention Jan Mot and his important contribution to developing an economy for immaterial arts, namely in representing artists such as Ian Wilson and Tino Sehgal. Other precedents of our interest include dealer and Conceptual Art Movement advocate Seth Siegelaub, Collectors Josée and Marc Gensollen, Belgian collector Herman Daled or the immaterial collection of art center FRAC Lorraine (Metz, France).

G

Meanwhile our engagement was first and foremost informed by the fields of performance, dance and choreography in Europe. The models at work in those fields rely on fundamentally different attitudes, when it comes to the understanding of objecthood, process, value and human implications.

First you cannot separate the process from the object: presenting a work always implies

extending its production. That production is generally based on human collaboration, so even presentation costs will not be limited to shipping and storing, but will imply specialized human labour.

Another aspect is that co-production with different parties sharing the material and financial responsibility to produce, present and circulate a work is the norm. We were interested in the impact these different attitudes could have on the art market.

DLF:

But why the need to bring these kinds of artworks to the conventional art market?

G:

Galerie operates as a Trojan horse of sorts, camouflaging as a commercial gallery in order to represent and deal impossible artworks for and in the art market. The goal was to reshape the debate about the performative turn and its economy from the inside. We thought alternatives should infiltrate and alter the official art system, to prefigure solutions in the middle of the art fair carpet. If the works were impossible, their representatives should inspire buyers that something else is possible. And so in our case alternative should wear the suit of convention rather than the cutting-edge outfit of marginality to manage its goal. And if we were to design experimental economic models, they were to be crossdressed as the most conventional procedures.

DLF:

Interesting, could you expand on your use of camouflage?

G:

In order to bring Galerie to full operativity we had to become indistinguishable from a proper institution, to the point of actually functioning as a real institution. The use of simulation and performance have been conscious tools to create the image of a well functioning entity: an image that comes to life and infects its context in return.

The fiction slowly made itself real and started to perform a certain authority.

DLF:

And why is it necessary to perform authority?

G:

Performing authority can be a tool to renegotiate power relations.

As representatives we have become institutional interlocutors to facilitate the desired conditions of the artists and the artworks. To the same degree that some artists create fake assistant email accounts as an image of professionalism (or a way to delegate unprofessionalism), having someone presenting themselves as your galerist knocking at the door of an uninformed institution, to facilitate a transaction on your behalf, can be very

effective.

DLF:

I sense that this performance goes deeper than authority, and your approach to representation also suggests a more, ahem, intimate relation to the artworks?

G:

As spokespersons, gallery owners act as accomplices of artworks, facilitating their circulation and protecting their interest: very often talking about the work is already manifesting it in a certain way, it is already making the work ‘perform’. And in the context of works dealing with performative and embodied practices, the function of representation can become even more blurry. In a sense, gallerists can become the best delegated performers of their artist… In our empty booths in Miami, Mexico etc… We represent a selection of artworks, using their own means for instance dancing an excerpt of a dance piece, giving a trial-session of a therapy format, engaging humor to represent a joke. To that extent, our bodies became a venue for the works to be represented. And the ‘gallery space’ thus became relative. No need for a rented venue since a speaking engagement, an invitation to an art fair or a workshop are all equally exhibition opportunities. In a way, wherever the galerists finds themselves is where the office, exhibition, studio visit or transaction can potentially take place. With #mybodyismybooth, Galerie simply needed to be accredited with a VIP pass to cruise the Swiss art fair VIP lounge and represent artworks at no cost.

G:

Well you still had to be involved with the performer of a famous German artist to get the VIP passes from the famous artist’s gallerist, who happened to have a booth at the fair. And the free drinks and the preview dinner definitely covered many of the costs associated with having the bodies of Galerie in Basel for four days.

DLF:

Mmmh. How does this embodied approach to representation relate to your, dare I say, rather idiosyncratic use of the term immaterial, because in fact, there is nothing immaterial about Galerie’s work, is there?

G:

Our mission is to promote works that cannot be reduced to a physical object or to the

documentation of an action. This definition points out a desire to shift away from the consideration that the value lies in what is left (the traces) or what establishes the veracity of what happened (the documentation).

G:

Meanwhile we do not desire to fetichize a medium that, as Peggy once said, “becomes itself through disappearance”. In a way everything disappears, rots. And it would be hypocritical to hide the fact that the materials that compose contemporary artworks often have a shorter life span than artists.

G:

So rather than valuing disappearance we prefer to attend to how the work appears: the doing, the happening of it, all its implications in spectators, gallerists, curators, friends of friends, institutions, etc.; and how the work suggests different relations to economy, production, distribution and acquisition.

G:

Yeah…We bet on the haunting rather than the ghosting.

DLF:

Mmmh..

G:

A few years ago, Galerie was invited by a collector of conceptual art to his apartment.

Usually collectors apartments are more or less packed with artworks. But this apartment, in a city where square meters don’t come cheap, was demonstratively empty: a lofty white space with a large sofa, 4-5 selected books on a table in front of the sofa, a desk and 3 chairs. The conversation went on with great gusto. The collector has been focusing his collection towards intangible artworks. His interest in acquiring experiences rather than artefacts led to many

questions about the ins and outs of Galerie. Eventually when it was time to go though, something happened: the collector went to a wall and revealed a secret drawer, out of which he produced a box with carefully wrapped documents – certificates. It was an impressive array of original certificates signed by the grand old masters of conceptual art.

Now. If this collector is interested in experiences rather than paintings. Then we could make a rough equivalence and say that he might be more interested in sex than Ferraris, but this certificate show gave us the impression that rather than sex he might just be more interested in reaaaaaaally fancy lingerie than the Ferrari.

DLF:

So how is your approach to immaterial arts different than that? And how does it relate to

value?

G:

Immaterial arts is an honest lie, of course endless living and non-living materials are implicated in Galerie’s work, but no physical object can account for the existence of the artwork. In a way, it’s selling artwork-as-practice or artwork-as-process: neither its mummy nor its birth certificate. The pricing is then depending on the work, established according to practicalities: shipping the artist, paying the labor to process the work; or as an extension of its aesthetics. Iterations of Humourology by Alex Bailey have hilarious pricing and editions of Internal Conflict by Krõõt

Juurak have seemingly arbitrary prices and there is no prior agreement between the artist and the gallery about how the money is split…. For most of the works it’s a combination of practical and aesthetic considerations that shape the economical format of the work.

DLF:

Can you elaborate on these considerations and how you develop the pricing?

G:

When we develop economical formats,we aim to challenge what an artwork can be as a commodity for the buyer. Somehow the illusory fixity of objects lures a habitual approach to think of artworks as if they were real estates: something unchanging, with a clear location, that you can resell. Even if there is a big desire to collect massages instead of real-estate, it seems as if many collectors and museums end up buying massages as real-estate, rather than massages as massages.

G:

So it becomes a question of medium consistency: We try to sell mood as mood, jokes as jokes, therapy as therapy, etc., we try to listen to the artworks to find clues for their “inherent” economy: how would it make sense for the artwork to express itself through economy, and

what does the artwork need from economy. We like to think about a sort of Speculative Essentialism, that is a term we have found to describe the posture behind our practice of listening to what the work needs: attending to an essence while assuming that we will never know for sure. The practice of listening, in the case of these works, becomes a matter of attending to the entanglements they weave with people, spaces, infrastructures and histories.

DLF:

I see, could you give a concrete example of how an artwork expresses itself through economy?

G:

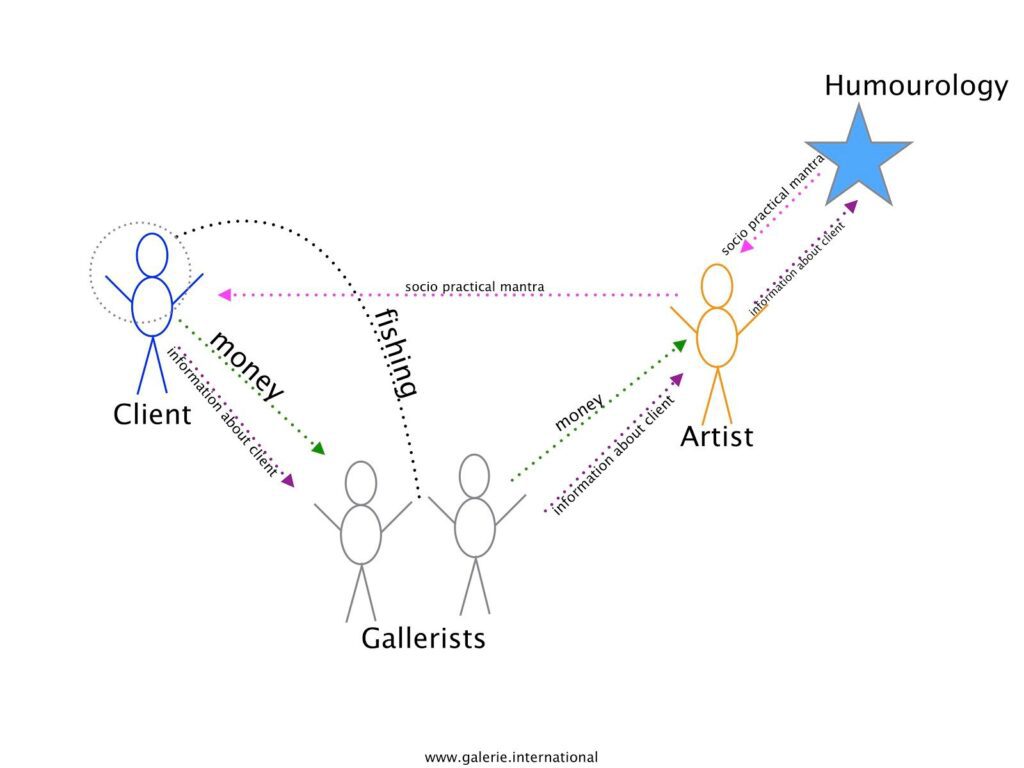

Yes, Humourology is a work by British artist Alex Bailey, that functions similarly to Numerology, but instead of getting a name, the client gets a joke. When selling it, Galerie gets information from the client, which we forward to the artist, who processes it through Humourology. Out of this process comes a socio-practical mantra (a joke), that is specific to the client. Galerie then meets up with the client again, gets the money, and facilitates the transfer of the work from the artist to the client, usually through phone. On the same occasion the artist gives some advice for the client about how to “hang” the work. Once the transfer is completed the client cannot resell the work, however they can retell it as much as they like.

The expenses of storing and presenting the work amounts to the client preserving and cultivating a sense of humor. By the way maybe you want one? There is a special discount right now € 99 down from €200!!

DLF:

Maybe we could talk about this afterwards 🙂 ?

Your example brings forth the position of the collector as a keeper of the work and the considerations about how such keepers implicate themselves in the presentation: it challenges the supposed autonomy of the artwork. I would argue that this is the case for any artwork, but in this case it becomes more explicit. In the process of acquisition you literally change the life of the artwork and the artwork literally writes itself into your life. But here the implication tends to be more difficult to circumscribe, to control. It opens up what acquisition could mean.

G:

It’s a simple shift. Acquiring these works means committing to keep them alive. Acquisition becomes closely bound to production: you activate it when you purchase it, you make possible its activation by investing in it. So in a way you don’t only engage with a finished product but you implicate yourself in the whole chain of production. And so you might find an artwork

haunting you for the rest of your life, or an artwork forming or ending a relationship.

DLF:

My Grandmother used to say: “We call the internet immaterial, because it’s hiding somewhere else”. In relation to what you just said, it makes me wonder whether immateriality could be a way to re-materialize art economy, to activate the social and material implications that are usually made invisible by the fetish of the art object and the abstraction of monetary value.

G:

My grandmother used to say “where there is a bouquet, there is a hand that picked the

flowers”. On top of that we could say there are also the bodies that smell and see the flowers, and the house the bouquet is in, and the relational and social impact of the bouquet.

DLF:

My next question is then if it works? Like the economy of it?

G:

We have sold artworks to private collections and public institutions.

DLF:

But If I understand your annual reports right, selling the works according to the economical formats you defined hasn’t been the only option, your approach to group exhibitions has also generated a substantial economy?

G:

Correct. We have presented a series of performed exhibitions, which we call Group Show. In these exhibitions we take the roles of both curators, gallerists, producers and, when necessary, performers of the work. Practically this means that the artists transmit the work to us either in the studio, through skype, protocol or other mysterious ways of communicating. For each Group Show the artists get an exhibition fee while not being present themselves (a privilege since in the case of performance usually the artist must be present).

G:

We have also done a variety of other curatorial projects, such as the Publication and the Intensive Curses in which we have involved the artists. Invitations of Galerie became an opportunity to extend the invitation to others and generate a context and income for their work.

G:

Lectures, workshops and presentations are also ways of publishing practices.

G:

And while this is all important, we also want to acknowledge that economy is about more than the moment money changes hands: The circulation of an artwork isn’t limited to its transaction, there is also the way people know about a work, the way their experience circulates from body to body. The more people are conscious and aware about an artwork the more value it generates. It is sometimes better for the economy and consequently life of work to be shown or presented or talked about or written about multiple times than bought once and hidden in a freeport.

G:

There are also the collateral repercussions of our work: indirectly artworks have been bought and sold through the circulation we have facilitated as representatives, yet without our direct involvement as dealers. That’s of course not in the first instance good business for Galerie, but as S. told you once in Acapulco: “if you love somebody, set them free.”