Joshua Serafin (b.1995, they/them), born in Bacolod, Philippines, moves like an idea, trained in the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Brussels, but belongs to none of these places. Their work, as much about inhabiting the body as escaping it, lingers on identity, transmigration, and queer politics. They craft rituals out of queer ecologies, assembling cosmologies that feel both ancient and futuristic. When we spoke, our conversation wove through modern mythmaking, states of being, and the pull of ancestral heritages taking the point of departure in their constantly evolving work Void.

The West has long mistaken its own image for a universal template, quietly exporting a worldview where nature is ornamental at best, instrumental at worst. Rooted in early Christian doctrine, this anthropocentric logic positioned humans at the centre of creation while animals, rivers, and forests were cast as passive matter, soulless, senseless, and serviceable. This is not just history; it still echoes through our contemporary frameworks where the natural world is parsed as determinate, mechanical, and ultimately mute. But belief systems outside this lineage suggest otherwise. In many Indigenous Cultural Communities of the Philippines, bodies, whether human or non-human (the wind brushing against a branch, the flow of a river, or the fuzzy body of a bumblebee) are not inert forms but sensuous presences capable of thought, memory, and desire. The Ifugao see their rice terraces not merely as agricultural tools but as living landscapes infused with ancestral spirits. For the T’boli, Lake Sebu and its surrounding forests are animate, inhabited, and responsive, a cosmology of interdependence where spirit and matter are never truly separate. What appears from a distance as myth may in fact be a finer kind of realism, one where the world is not only alive but listening.

American philosopher David Abram observes in The Spell of the Sensuous (1996) how we’ve shed the old language, the dismissive tones that once called the shaman’s spirit guide “primitive superstition.” That particular ethnocentrism, at least, has been scrubbed from our vocabulary (yet we still, out of habit or need, name these mysteries “supernatural,” as though nature itself were too orderly, too subdued for anything so strange). In each Indigenous world, this shift, this fluid dance of being and becoming, finds its own shape, shaped by the land that shelters it. Often, it’s something unseen, a thin shimmer between what is and what we sense, an invisible breath that moves within and between all things, binding what we can see to what lies just beyond. This glue binding together the physical and the unrevealed is materialized as a thick black goo in the work of Serafin. A primordial goo revealing and hiding the past, present, and future, speculating in alternative futures and a non-linear past. I caught Joshua at a rare moment of stillness last year the first time they had spent a full month in Belgium, where they’re based. Usually, they’re on the road for months at a time, performing everywhere from Amant in New York and Haus der Kulturen in Berlin to Esplanade in Singapore, TONO Festival in Mexico City, and the Venice Biennale. Joshua and I spoke while the sun was casting its rays of light, Joshua’s face enfolded with golden hues, and my green sequin top glimmering on screen as we discussed their practice, ambitions, and influences.

Olivia Turner [OT]: Do you see performance as a site of healing? You’ve mentioned healing a few times, both in terms of the process and the content of the work. How does this idea of healing shape your approach to the experience as a whole, particularly the dynamic between performers and those watching?

Joshua Serafin [JS]: Yes, I see performance as a space for healing. In Pearls, for instance, the performance is explicitly about healing, not just for the audience but for the performers as well. To create a work centered on healing, the process itself had to be healing for everyone involved. That meant fostering an environment where my collaborators felt truly heard, where they could express themselves fully. Healing, for me, isn’t just about the final product; it’s about the journey we take together to get there.

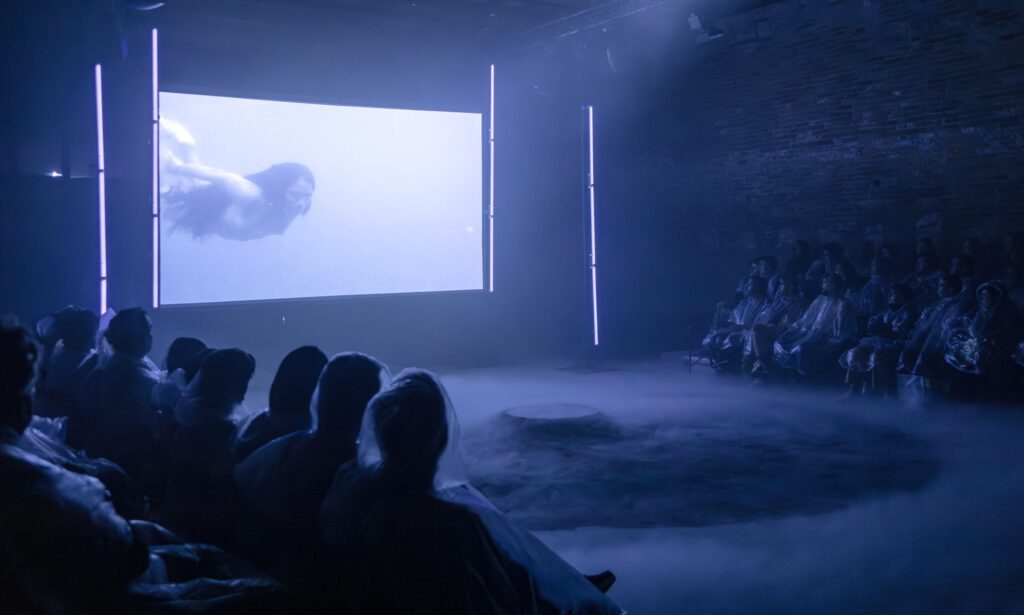

When it comes to the experience, I think of it as something shared. In some works, I break the fourth wall and invite direct participation, while in others, like Void, the connection is more subtle. Even without overt interaction, I’m always aware of the presence of those watching. It’s all part of the same energy, the same atmosphere. I want the experience to feel like something we’re all in together, a collective process rather than a division between performers and observers.

*

Celia de Villiers argues that performance artists are modern-day shamans. I would say that although one cannot upheave performance artists to the religious standpoint of the shaman, they use mutual devices to facilitate an engagement and encounter between the ‘audience’. The performance artist relies on a range of dramatic devices to encourage viewer participation; utilizing props and skills, the performer pursues a range of communicative tools founded on a variety of intentions. Like a shaman, the artist creates a space where viewers can explore and reshape their beliefs, connecting them to a shared system of ideas and meanings.[1] Joseph Beuys serves as an example of how performance artists have been metaphorically framed as shamans for the art-viewing public, in which mythmaking and narratives rooted in Indigenous cultures were integral to Beuys’ self-construction. Likewise, through his performances, Serafin connects the audience with concepts of ecology, life cycles, and regeneration, evoking a ritualistic experience of an otherworldly sermon and providing a space for world-building.

Serafin, Joshua. Cosmological Gangbang: PEARLS. Performance with Lukresia Quismundo and Bunny Cadag. Viernulvier, Ghent, 2024-. Documentation by Michiel Devijver and Maryan Sayd.

OT: Your work feels like it navigates the intersections of spirituality, ecology, and queerness, particularly in how it addresses both the past and the future. It seems positioned between looking back, toward pre-colonial, Indigenous traditions, and looking forward, toward speculative, almost sci-fi futures. How do you manage that tension between these two temporalities?

JS: It’s really about inhabiting that in-between space. I’m fascinated by pantheistic ideologies; the multiplicity of gods and how different cultures see one entity morph into various forms. That constant transformation is what captivates me. When I started researching Philippine pre-colonial mythologies, I was told it’s impossible to truly ‘go back’. So, I thought, if I can’t go back, I’ll create my own myths. Based on what I’ve learned, I craft my own mythology rooted in personal experience but also speculative.

In one project, I visited the Talaandig Manobo community in the Philippines. They’ve preserved many of their ancestral practices, and spending time with their datu, a leader and shaman, was transformative. Their worldview integrates gender, sexuality, nature, spirit, and body as interconnected. There’s no hierarchy with humans at the top; instead, everything is part of a larger, living ecosystem. That sense of connection, that everything is alive, is something I carry into my work. For me, the future isn’t separate from the past; they’re two sides of the same living, evolving myth.

*

Serafin throws out the binary between past and future like last season’s theory trend, and instead offers a mythic continuum where time sweats, mutates, breathes. It pulses with queer temporality not as identity politics, but as a refusal of tidy origin stories and capitalist endpoints. Here, memory and speculation don’t take turns; they overlap, like a bruise on a dream. There’s no desperate nostalgia or utopian clickbait, just a slow, deliberate re-enchantment that rewrites mythology from the inside out, using lived experience as both raw material and glitch. To consider non-Western performance practices is to enter a landscape where the intersections of technology and materialism often feel underexplored, at least through the lens of Western critique. It hadn’t occurred to me, not until speaking with Serafin, how much the discourse surrounding non-Western performance remains ensnared within the architecture of Western thought, an imposition of frameworks that flatten, distort, and constrain what they claim to illuminate. The prevailing frameworks we rely on; Heidegger’s warnings about technology’s enframing, Lepecki’s meditations on stillness, Barad’s intricate choreography of matter and meaning, Haraway’s cyborg provocations are rooted in distinctly Western traditions. These perspectives, born from industrialization, Cartesian dualism, and modernity’s ruptures, dominate global discussions of performance and technology, creating an apparent imbalance.

Serafin, Joshua. Cosmological Gangbang: PEARLS. Performance with Lukresia Quismundo and Bunny Cadag. Viernulvier, Ghent, 2024-. Documentation by Michiel Devijver and Maryan Sayd.

Lepecki, for instance, grounds his critique on the Western body’s resistance to mechanization.[2] Barad situates agency in the material-language entanglements of quantum physics.[3] Haraway, with her cyborg manifesto, collapses boundaries between the organic and the mechanical, reflecting anxieties and aspirations of a post-industrial, technocratic West.[4] These ideas, though universal in ambition, remain culturally specific in origin. Eastern philosophies, by contrast, have traditionally engaged technology through metaphysical unity or spiritual integration, often treating it as an extension of human purpose rather than a disruptive force.

What’s often read as detachment may simply be a different mode of engagement, one that doesn’t rely on the West’s compulsive need to critique through conflict. Traditions like Zen, Taoism, and Hindu cosmology don’t ignore tools or technology; they absorb them into wider systems of meaning, where form, function, and spirit aren’t at war. Instead of oppositional analysis, there’s attunement, integration, a kind of quiet attention that doesn’t ask to be called critical, but is.

Heidegger’s notion of a gap between thinking and technology seems mainly Western, emerging from Europe’s grappling with industrial modernity. However, applying this gap universally risks oversimplifying Indigenous contexts, where the relationship between thought and technology has evolved along different trajectories, often less combative and more integrated. What the East may lack in overt technological critique, it compensates for in frameworks that seek to balance materiality within holistic systems of meaning, as present in Serafin’s practice. Serafin’s performances highlight the convalescence of materiality and technology, in which an ancestral awakening stands side by side with digital screens and an electronic soundscape. A sense of missed dialogue remains in Western perspectives, a silence born not of absence but of misalignment. The frameworks we lean on are not theirs, and their critiques are not ours.

The challenge, then, is not to frame Eastern traditions as deficient but to create space for their voices; voices that might reshape the conversation entirely. Only by fostering genuine cross-cultural dialogue that respects these different modes of engaging with technology and materiality can we move beyond the limits of any single tradition and find a richer understanding of performance, embodiment, and ontology.

In their performance Void a strange terrain unfolds, a mist hovers over damp soil, and blue light encloses the space. From a patch of earth, Serafin rises, slow and deliberately, their body sheathed in a viscous black slime, catching the faint blue light, slick like gasoline, thick like glue. It clings to them like some alien membrane, shifting between the sheen of oil and the heaviness of tar. Dressed in a loincloth, their body stands sculptural, almost animated. Long hair streams down their back, their eyes are pitch black and glossy, meeting the viewer’s gaze with a void-like intensity, unflinching, as if Serafin has emerged not from soil but from some liminal otherworldly space. Their movements interchange between quick reptile movements and slow, calculated gestures. They throw themselves into the soil, submerging themselves in the black goo; with every movement, the goo follows, becoming a phantom performer, a physical shadow. Serafin is neither a symbol nor a metaphor but something more ancestral that resists our need for meaning, standing instead as a provocation, a rupture in the familiar terrain of the visible word. The dance is ritualistic, a summoning of ancestors and future descendants, figures from both the irretrievable past and the imagined future. Serafin bridges the past, present, and future by juxtaposing pre-colonial folkloric traditions with images of a speculative, almost science-fiction future, the disquieting interplay between what was and what might yet be. The performance is accompanied by a soundscape produced by Alex Zhang Hungtai and Calvin Carrier, an intricate tapestry of sound weaving through the performance with a haunting fluidity, shifting between the organic and mechanical. Almost as if the music breathes alongside the performers and the audience, it becomes a part of the performance’s very fabric, creating an immersive sensory experience.

OT: Your work seems to approach unpredictability in fascinating ways. How do you perceive the agency of the materials you use? Are they collaborators with a will of their own, or tools you shape to your vision? And how does this idea of agency tie into your sense of time, which often feels circular and timeless in your performances?

JS: I definitely see the materials as living entities. Water, for example, isn’t just an inert substance; it’s alive. It transforms, and in doing so, it allows me to transform as well. The black liquid in Void has this phantom-like quality; it appears, it disappears, it moves in ways I can’t always control. So, the materials have their own agency, and part of the performance is about surrendering to that, letting the materials shape the work as much as I do.

When it comes to time, I see it as fluid, something that mirrors the agency of the materials. Each performance has a beginning and an end, but the narrative isn’t linear. Everything is interconnected. One piece overlaps with the next, feeding into each other like a continuum. My practice is never about completing something definitively. It’s about embracing evolution letting each moment, each material, shape what comes next. Nothing is ever truly finished.

*

The soundscape moves through the performance, acting as a voice in its own right, but the absence of human sound – silence – shapes the work. In Serafin’s performance, silence is not a void but an intentional presence. It resists convention, allowing the piece to unfold in a space where sound and its absence hold equal weight. Professor Kalpana Rahita Seshadri’s HumAnimal: Race, Law, Language offers a compelling framework to analyze Serafin’s work, particularly in how silence operates as a tool for empowerment and resistance.[5] In HumAnimal, Seshadri examines the intersections of race, law, and language, highlighting how silence often dismissed as absence or submission, can function as a powerful site of agency and subversion.[6] This aligns closely with Serafin’s use of silence in Void, where the absence of sound becomes a presence, challenging normative frameworks of performance and communication. Silence has the capability to “empty” language, meaning it disrupts or resists the dominance of language enforced by societal structures. Here, silence is framed as an active participant, a political potential that challenges the authority of language, which is more often than not tied to systems of power and control. As earlier mentioned by Serafin, they perceive time as fluid and non-linear. Likewise, Seshadri indicates that the nature of silence, in terms of its spatial temporality, operates across space and time as a dynamic force with ethical significance rather than a static absence. In Void, Serafin appears as a liminal figure, neither human nor animal. Through this approach, they reveal how silence can be an alternative way of being or interacting with others, moving beyond conventional language and power dynamics to create new possibilities for understanding and connection.

OT: Your work often feels fluid and transformative, as if it moves between worlds, drawing on the shifting, expansive qualities of water while channelling a deeply spiritual, almost shamanic energy. This sense of openness extends to your collaborations, where performers seem to shape the work as much as the materials themselves. How do these interconnected ideas of fluidity, spirituality, and collective creation influence the way you approach performance?

JS: I’m really drawn to the idea of constant movement and becoming. It’s why I gravitate towards liquids and materials that change form. Last year, I learned to surf, and that experience, especially when a wave knocks you down and everything goes quiet, felt like being in a womb. That memory stayed with me and influenced my work on Pearls.

Performing Void feels like an exorcism. I surrender to the material, to the soundscape, and let myself be transformed by the spirits I’m channelling. It’s a space where I invite alter-egos or spiritual entities to inhabit me. With Pearls, it’s a similar process, though the atmosphere is thicker, more layered. It’s about acknowledging the presence of something beyond ourselves.

Collaboration is also crucial for me. For Pearls, I worked with Bunny and Lucretia because of their unique practices and the narratives they bring. When I invited them to join the project, I asked, “If you were an entity, what would you be?” They chose their own elements: earth, fire, wind, water, and we built the performance around that. It became about dreaming and creating together, letting each person’s vision shape the work.

*

Perhaps what lingers most is not the choreography or the symbolism, but the quiet insistence that something else is possible. Not a resolution but a reorientation, a soft undoing of inherited categories where the edges of the body blur and the language of critique slips into something wetter, more sensuous. Serafin’s work doesn’t so much answer questions as it dissolves them, letting meaning seep sideways into sensation, into silence, into the thick black ooze of becoming. In these performances, myth and matter fold into one another, and time bends just slightly, enough to suggest that past and future may already be touching. We’re asked not to interpret but to inhabit, to feel with rather than think about. The work doesn’t stage an argument; it stages a shift, one that unfolds through movement, texture, and shared breath. It invites us to sit with uncertainty, listen differently, and imagine that the world is more alive and entangled than we’ve been taught to believe. And maybe that’s what stays with you long after the lights fade, not what the performance meant but what it changed.

Bibliography

Abram, David. 1996. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Vintage Books.

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

de Villiers, Celia. 1998. “The Performance Artist as Modern Day Shaman.” In Proceedings of the 11th Annual Conference of the South African Association of Art Historians. Pretoria: SAHRA.

Haraway, Donna J. 1991. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 149–181. New York: Routledge.

Heidegger, Martin. 1977. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Translated by William Lovitt. New York: Harper & Row.

Hui, Yuk. 2016. The Question Concerning Technology in China: An Essay in Cosmotechnics. Falmouth: Urbanomic.

Kasulis, Thomas P. 2002. Intimacy or Integrity: Philosophy and Cultural Difference. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Lepecki, André. 2006. Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement. New York: Routledge.

Parkes, Graham. 1993. “Zen and the Art of Technology.” In Technology in the Western Political Tradition, edited by Arthur M. Melzer, Jerry Weinberger, and M. Richard Zinman, 153–174. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Seshadri, Kalpana Rahita. 2012. HumAnimal: Race, Law, Language. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Serafin, Joshua. 2023. “Void.” Performance. Various international venues.

Villalón, Aurora. 2018. “Indigenous Ecologies and Animism in the Philippines: The Case of the T’boli and Ifugao.” Journal of Southeast Asian Cultural Studies 5 (1): 33–47.

[1] Celia De Villiers, “Contemporary Performance Art as a Hermeneutic Pathway to Transcendence and Healing.,” Art&Sensorium 1, no. 01 (May 8, 2014): 117–35, https://doi.org/10.33871/23580437.2014.1.01.117-135.

[2] André Lepecki, Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement (New York: Routledge, 2006), esp. pp. 5–11.

[3] Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), pp. 132–168.

[4] Donna J. Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), pp. 149–181.

[5] Kalpana Rahita Seshadri, HumAnimal: Race, Law, Language (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), xiii–xiv.

[6] Ibid., 3–7.