As part of her series ’Living Archives’ curator Lotte Løvholm interviews artist Miriam Kongstad about her practice. Miriam unfolds the research going into her works Take My Breath Away (2023) and Worker’s Choice (2017) with references to pop culture, aging bodies, women in jeans and body politics.

Lotte Løvholm: Thank you for doing this interview with me, Miriam! You premiered a new commissioned piece titled Take My Breath Away, in March this year, for the New Carlsberg Foundation’s annual award ceremony at Glyptoteket in Copenhagen. Could you talk me through the process of creating a new performance for such a specific context?

Miriam Kongstad: Like many of my other performative works Take My Breath Away is relating to a specific site, and in this case the piece is both shaped around the very vibrant and loaded architecture and interior of Glyptoteket, but also the specific occasion of the premiere. Glyptoteket is a museum of ancient art, displaying the Carlsberg collection of primarily Greek and Roman sculptures. It takes quite a lot to carry such a grand space, filled with sculptures, mosaic floors and tall marble pillars. The space is huge and the acoustics crazy. Apart from that, the piece was premiered at an award ceremony with a specific and invited audience. To be commissioned for a very specific occasion or context can feel challenging because it really sets the tone and frames your work, but ultimately I’m excited by challenges and find it quite generative. With this project I wanted to be aware of the context and integrate it in the piece, but ultimately create a piece of art which can function just as well outside of this specific occasion. I think, with a bit of humour, I managed to do so. To play with both the occasion and the weight of history and time at Glyptoteket.

Lotte: How was your process navigating the specific context and architecture to the thematic content of the piece?

Miriam: My starting point was a reflection on how collective and ceremonial events have been missing during the COVID years, and how people who are not usually into sports for example, suddenly felt an impulse to go to football matches, basically to feel part of a collective body after society reopened. You find this collective excitement and interconnectedness in many forms and different places in life, whether it be in sports, concerts, or various ceremonies like weddings or funerals. They’re all different forms of rituals of togetherness and containers of collective emotionality. I began to think through these various forms of rituals as connected to how we deal with emotions in public space. Especially in Scandinavia, emotionality is something we’re raised to reserve for the private sphere, but then we have these cultural moments of rituals where emotionality is socially accepted. A ritual, as the French philosopher Roland Barthes describes it “protects us against the abysses of being. A ceremony protects like a house, something that allows one to live in one’s feelings. The ceremony of mourning acts like varnish, protects, insulates the skin against the atrocious burns of mourning. When there are no rituals to act as protective measures, life is wholly unprotected”. This way of thinking about rituals and ceremonies resonates a lot with me.

I wanted to make a performance which would evoke emotions in an audience, something breathtaking so to speak. That’s easier said than done. I had a time constraint of 10 minutes due to the context of the premiere, so this is the shortest performance I’ve ever made. Instead of fleshing out a narrative, I wanted to transmit a tactile experience, give space for emotions. Something more sensorial than cognitive. I started looking into the notion of catharsis which is an ancient greek term, derived from Aristotles who defined it as the moment in a theatre play where the audience are allowed an outlet of emotions. A cleansing through emotionality. Later, in late 19th century Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud reintroduced the concept of catharsis, this time within the field of psychology, as a method to treat trauma, but also focused on the treatment of hysteria. In this context emotionality became gendered and seen as a predominantly female domain. Something which has shaped our contemporary society as well. The social hierarchies around emotionality is quite strictly defined, even today. I thought it was interesting to compare ‘the hysteric’ and ‘the pathetic’ in regards to gender connotations and the socially acceptable.

Lotte: Did you explore the term catharsis in regards to recent, contemporary contexts as well?

Miriam: While developing the piece I was reminded of the iconic moment in 2003 where Madonna kisses Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera on stage during the MTV music award ceremony. It happened exactly 20 years ago and at that time it was such a no-go for women to express any form of attraction towards each other in public. It made me wonder where we’re at today and I used this kiss as a visual reference in the performance. Also, the famous sculpture The Kiss from 1882 by Auguste Rodin, which is one of my favourite sculptures, is on permanent display at Glyptoteket, so it all came together at some point. When I run into loops like that, I know it’s right.

Lotte: I remember this kiss at the MTV awards in 2003. Watching it as a teenager I found it quite awkward, mostly because it was so staged. Which emotions were you investigating with your kiss at the end of Take My Breath Away?

Miriam Kongstad, Take My Breath Away, 2023. From the premiere at Glyptoteket, Copenhagen.

Commissioned by New Carlsberg Foundation. Photo: Malthe Ivarsson

Miriam: What stood out to me was how scandalously this kiss was treated in the press and the public. How much rage and shaming it caused, and this was only 20 years ago. Nevertheless, it also served as some kind of collective catharsis, and one of the early little scratches in the surface of public queer life. In 2003 the idea of female sexuality as something other than directed towards men was still not mainstream. It still isn’t. But had this kiss happened today the reactions would have been different I believe. So I guess, to some degree, I wanted to test that out for myself, how an audience would react to a lesbian kiss 20 years later?

Lotte: Can you set the scene for Take My Breath Away and describe how you structured the piece?

Miriam: The performance is structured as a ceremonial act with Francesca Burattelli on saxophone and myself on oboe, slowly walking down the aisles in between a sea of people and near endless rows of seats in the main space of Glyptoteket. We’re entering the space from the back, walking towards a huge LED screen on the stage, which intensifies in brightness during the performance, eventually bathing the whole space in light. Dancer and choreographer Sigrid Stigsdatter Mathiassen is opening the performance, starting on stage, jumping falling, and building up tension, before moving into a circular run around the edges of the space, creating a traction between her fast-moving and circular pace and the almost slow-motion and forward facing direction of Francesca and me. Accompanying an electronic soundscape, Francesca and I are playing a live composition based on quotes from classic pop songs by artists such as Céline Dion, Whitney Houston, Toni Braxton and the Top Gun soundtrack ‘Take My Breath Away’ by the band Berlin, which the performance lends its title from. Through the musical composition I wanted to create a feeling of something subtly familiar. To evoke a subconscious feeling of familiarity, but without being able to quite point it down. Eventually all three performers meet on stage, in front of this brightly lit LED screen, where Sigrid and I perform the kiss while Francesca plays a fragment of ‘Careless Whisper’ by George Michael. The closing scene is somehow too much, cheesy, cringe. But that’s exactly how I wanted it, I wanted to explore this ‘too-muchness’ and ambivalence, and to sincerely feel something myself, not simply perform or pretend.

Miriam Kongstad, Take My Breath Away, 2023. From the premiere at Glyptoteket, Copenhagen.

Commissioned by New Carlsberg Foundation. Photo: Malthe Ivarsson

Lotte: Before moving on to other works of yours, could you talk about your educational background?

Miriam: In 2013 I moved to Berlin to do my BA in choreography and performance at the Inter-University Center for Dance Berlin (HZT), which is part of Universität der Künste Berlin. It’s a relatively young school and a counterpoint to more traditional dance educations. During my studies I often got encouraged to do a master’s in visual arts. I always wanted to do everything myself: perform, do the choreography, the props, compose the sound, set the lights… That was and still is the way I approach my work. At times I have collaborators, of course there are skills I don’t master, and I enjoy that process too, but when I start a new work it’s always a total image and a package containing all aspects. I’m not good at outsourcing.

After graduating from my BA in Berlin, I went to New York for an internship at the project space Participant Inc which was an extremely formative time for me. Observing the New York art scene at a young age, made me realise the privileges of being an artist in Northern Europe, the expectations and possibilities you have at hand. I experienced a different passion and urgency in the USA. Also, at Participant, I was blessed to get an intimate insight into the works of the late artist Ellen Cantor. I instantly felt connected to Ellen’s work, and the way she played with performativity both in her early paintings and sculptures and later in her videos and films was a big eye-opener for me. From then on I started working more and more with objects and materials other than moving bodies. During this process I realised that my life as a performer, for so long had been constructed around maintaining my body and staying in shape, so there was something so liberating about working with external materials. In 2018 I then moved to Amsterdam to do my master’s in Fine Arts at the Sandberg Institute.

Lotte: Alongside a manifold of materials and formats, you still use your body quite a lot in your works, so I wonder if you still have that mindset of a dancer looking at body maintenance?

Miriam: Something that connects each element in my practice, that being images, sculptures, sound or live performances, is indeed the presence of bodies. In the end, my work always deals with issues and topics related to the human body, even if as an expanded notion.

In that sense bodies are always present in my work, whether that’s my own body performing, depictions of bodies or analyses of body politics, looking at gestures or body language for example. I like to approach choreography as a tool to analyse society.

In regards to my body as material, I still keep up a daily movement practice, but far from as intensely as when I studied dance. Utilising your own body as your main material in artworks is interesting but quite inconvenient from a longterm perspective. What happens to pieces once you grow older? I’m only 31, but I surely feel I’m not 21 anymore. It’s a different body. On the one hand there’s something quite exciting about returning to pieces I’ve created in my early 20s with my current knowledge and the aging of my body. But it’s also troublesome and difficult and at times painful, too. There’s a very direct trail of time.

Lotte: How do you work within this factor, aging and time, in your practice?

Miriam: I was most strongly confronted with this question in 2020 when the National Gallery of Denmark acquired my performance Worker’s Choice for their collection. This was the first time I was really faced with considerations and formalisations of the longterm life of a performance. What would happen with the piece once I’m no longer able to perform it myself, no longer alive? The work is conceptually made for two young female bodies, so there will be a moment in time where I’d have to pass on the torch.

Lotte: In terms of the acquisition agreement what did you decide on?

Miriam: I decided that as long as I’m alive, it should be a conversation between the museum and myself, whenever they’d wish to show the piece live. In the agreement it’s stated that after my death the piece shall be performed by young female performers. Apart from age, there are multiple other factors stated in the agreement. Choices I only really became aware of in retrospect. It’s interesting to experience how performances change through changing and diverting bodies, because it’s a format ultimately composed out of living matter.

In Worker’s Choice there’s a strong point in the performers being young females, but I could also imagine reenacting the piece when I’m in my 60s somehow. There are so many unspoken rules and shame around the aging female body. It would add a new layer to the piece.

Lotte: To give a bit of context, Worker’s Choice is performed by you and another female performer clad in denim from top to toe, with buckets of water and a very present soundscape. The choreography is based on research you made on jeans as one of the earliest examples of the advertisement industry’s construction of objects of desire. Could you describe the research behind the piece?

Miriam: Worker’s Choice is a performance based on the history of jeans, specifically the depiction of women in jeans. Originally jeans and denim as a material in the West, was meant as workwear for men in the mines, back then a purely masculine domain. It wasn’t until around the 1950s that jeans became a more widespread fashion item and acceptable for women. Together with cigarettes, jeans were one of the first consumer items to be linked directly to the construction of identity. The birth of modern day advertisement. Introduced by Edward Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud, there was a shift from consuming out of need to buying out of desire, and both cigarettes and jeans were utilised in advertisements as symbols of the liberation of women. From this moment onwards advertisements started educating us about how our bodies should look, move and behave, and in that way subconsciously construct desires..

While working on Worker’s Choice I created an extensive collection of visual depictions and advertisements of women in jeans, from the very early start up until today. I analysed how the imagery had changed over time, landing on today’s more trending “gender neutral” aesthetics. Looking at this massive amount of images I’d gathered, I was struck but how men and women would be portrayed so very differently in jeans. Men in jeans would mostly be depicted out in open territories, often the desert referencing the birth of the Western masculine male. Yet, most ads depicting women in jeans would have the model pose in an enclosed space, with some form of clearly defined backdrop.

Lotte: Sadly, this could be mirroring how women’s domain has been tied to the home, an enclosed space, and men’s the public space.

Miriam: Indeed, and all these models in confined spaces are also symbolic of the major contradictions within the history of advertising jeans to women. As mentioned before, jeans were used as a strong symbol of female liberation, but simultaneously loaded us with body ideals, restrictions and norms, it created a sort of fashionable confinement.

Jeans also quickly became a cultural symbol and entered the social sphere. I remember my mom telling me about her first pair of jeans as a very memorable moment in her youth. People would spend time together customising their jeans, and it wasn’t uncommon to buy extremely tight jeans and go into the bath tub or the sea wearing the jeans, leaving them on to dry in order to adjust and fit the individual body shape perfectly. I think we all know the image of a woman struggling to pull a pair of tight jeans over her hips, completely squeezing her intestines. This type of clothing is first of all anything but comfortable, but even straight up unhealthy. It’s a kind of contemporary corset. But women’s fashion and beauty standards have long been centred around some degree of dis-ability. Long nails, dresses, high heels, make-up. It all plays into the idea of the woman as being somewhat ‘passive’ – the cherry on the top of the cake, which we can enjoy the beauty of, while the man is out in the field doing the hard work. It’s a really dusty but stubborn narrative, and it’s interesting to see how there are many different approaches to dismantling and reappropriating this nowadays.

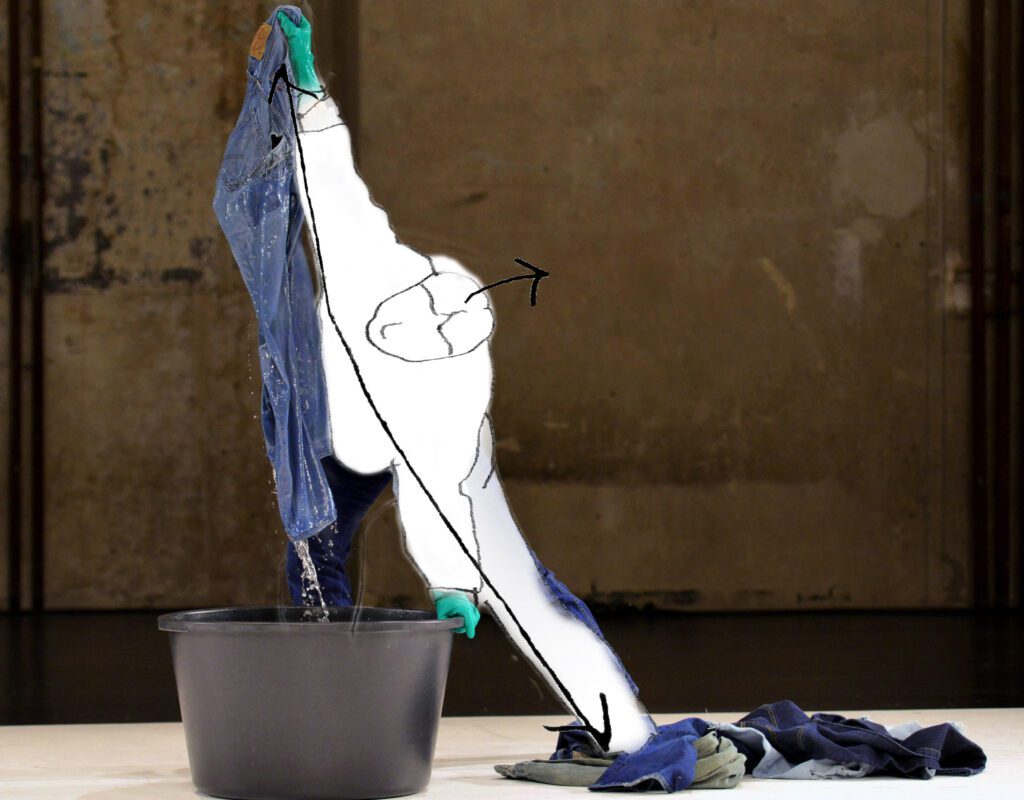

Choreographic sketches for Worker’s Choice, 2017

Lotte: Can you describe how you developed the choreography for the performance using this collection of images?

Miriam: Scrolling through hundreds and hundreds of images every day I realised how these images are constructing and compartmentalising our thoughts. Advertisements ultimately play with the construction of desire, the construction of identity and self-image. Nowadays, advertising takes place in other forms than in the 1950s, but it doesn’t mean it is not there, rather the opposite I’d say. It’s integrated in daily life in a much different and more sneaky way. The choreography in Worker’s Choice is directly built on these advertisements of women in jeans I had gathered. I selected the ones that stood out the most to me, reduced the visual input by drawing the outlines and contours of the bodies and removed all other information in order to isolate the positions of the bodies. In this way I could better analyse and compare the body language. I would then group the drawings and embody them in the studio. Step by step I would find ways to move from drawing A to B to C etc. What would these body postures feel like, and how would it be to turn still images into moving sequences? A big part of the performance is constructed in this way, by embodying the visual sources. For me this was a new way of working at the time, and it was all a bit of an experiment to feel for myself how it would be to become these models and hold these body positions. There was a lot of awkwardness involved.

Lotte: Yes, I have a small concession, Miriam, during all of my teenage years I was a model and I do indeed know all about these uncomfortable positions.

In terms of body politics what did you make of these poses?

Miriam: There’s something quite violent and constructed when it comes to female body language. Something kind of held and constricted. The female body is most often portrayed guarding off her inner body surfaces: crossed legs, closed arms, feet turned inwards, making yourself smaller. It’s so ingrained in us, we often don’t realise how we learned to carry our bodies. It was quite revealing for me at least, and after this project I surely became more aware of how I present my own body.

Lotte: I have one last question for you, because I’m reminded about how my own obsession with performance art and body politics is linked to my experience of being a model as a teenager in the 00s, which of course meant learning to reconstruct specific female ideals and tapping into advertisement companies’ ideas about desires at an early stage of my life. This rehearsed choreography is such a part of my body now, that I’m not even aware half of the time. I wonder where your interests comes from in terms of revisiting the body as a political site in your practice?

Miriam: The short answer is: being a woman. Always carrying an unavoidable awareness of my body and what it means to bring that body into any given space. Danger, violations, implicit corrections, politics, and also pleasures and fun. I think about where all of this derives from, how we learn these behaviours, movements and social choreographies, ways of navigating the world basically. I grew up at the countryside, on a farm, quite remotely, with an older brother. We both didn’t go to kindergarten, didn’t watch much TV etc. My whole world really started at this farm with my brother by my side. My best friends were animals, and still, these gendered choreographies sneak in. The construction of desire, identity and gender happens everywhere, even in the cow shed.