All all all on collaborative, anti-hierarchical, and transparent curating.

During the last couple of years, All all all has softly reshaped ways of thinking about art institutions, exhibition formats, and artistic labor. Launched in 2022 as part of an open call in a basement venue at Gl. Strand in central Copenhagen, the platform was initiated by Klara Li to challenge the existing paradigms of what a good life with art can be.

What emerged is one of the most exciting contemporary art spaces in the city—a shifting, process-oriented, ‘open-source’ approach to art practice that refuses to settle into comfortable institutional norms and categorical differentiations regarding either disciplines or work titles. I sat down to talk with the two curators of the platform, who, apart from Klara, counts Sif Lindblad.

“I had just finished my degree in art history and was deeply uncertain – both morally and existentially – if I wanted to continue working with art,” Klara recounts about the beginning of All all all. “But I thought: if I were to work with art, what would make it meaningful and at the same time contribute to living a good life?”

That question led to a proposal submitted to Gl. Strand based on what she called a ‘care-based arts practice.’ It emphasized anti-hierarchical structures, collective processes, and an insistence on more time and space within exhibition projects—an antidote to the often-exploitative speed and expectations of traditional institutions. “I didn’t want to create yet another space for emerging artists that simply repeated the same extractive structures,” she says.

Residency exhibitions and live arts expansions

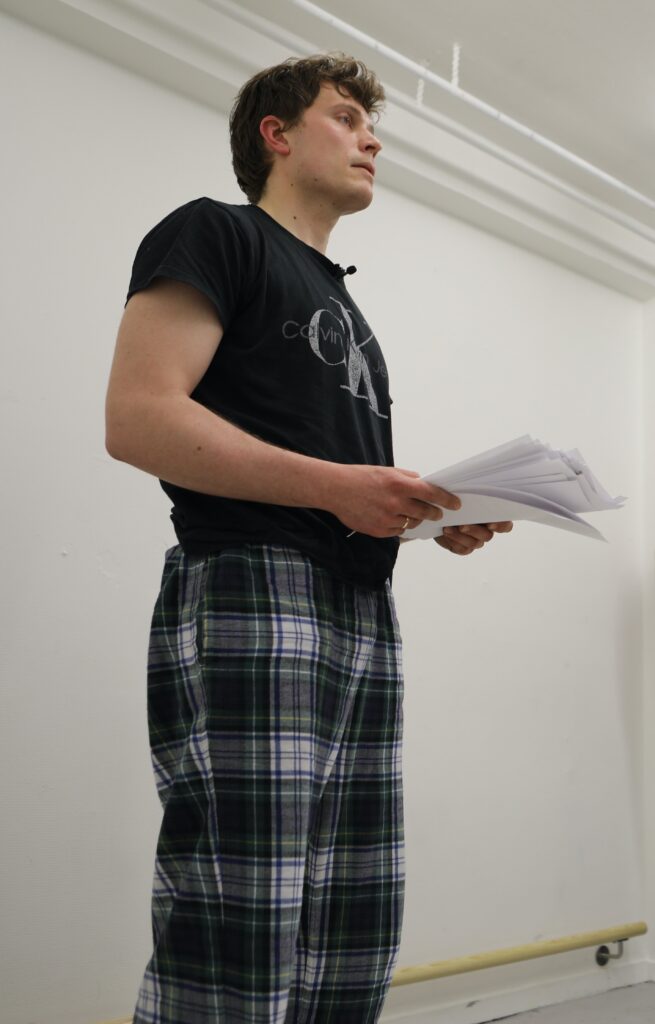

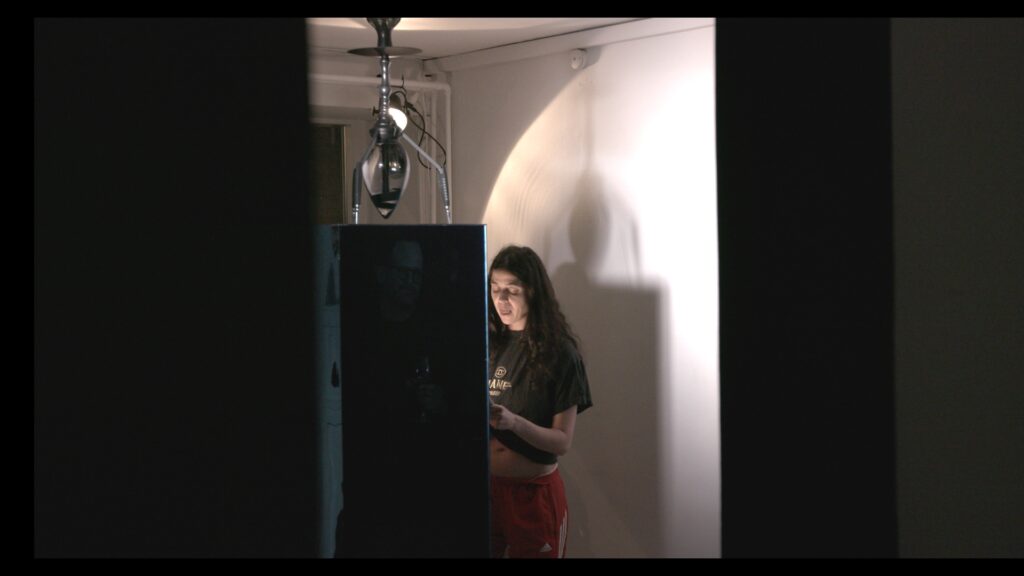

Instead, All all all evolved into a residency-based exhibition program: artists are handed the keys to the space, invited to develop a project for 1-2 months, and eventually open the doors to the public—not with a finished product, but with artworks in progress. The goal is to challenge the idea of the ‘finished’ art object and of artistic processes as individual and end-goal oriented, making space for longer timeframes and more sustainable and collaborative conditions for the artist. But also, for new audience experiences focusing on production aesthetics that often aren’t accessible in more traditional institutions:

Klara: “It was also about asking what an art experience could be. What if the sustainable process for the artist became something the audience could engage with and derive value from in new ways?”

The first year, five artists with highly diverse practices—including writing, sculpting, and painting—were invited. Each was paired with another artist of their choice to create a live response to the exhibited works later in the process.

“That was something Sif pitched,” Klara says, pointing to the platform’s other curator, who was then working at Gl. Strand but later became part of All all all.

“The chosen artists were not expected to interpret the resident artists’ work,” Sif clarifies. “It was more about expanding on it, in an outdoors and live format.” This reflects an almost ecological movement within the platform where ideas and gestures are incorporated by other artists continuously and then expanded upon in new contexts.

One of the most notable results of this movement was the live collaboration between Julie Falk – in-residence at All all all at the time – and Zahna Siham Benamor. Siham wrote a prayer for Julie, and this became a foundational step for her later performance practice which now makes up a substantial part of her work. That prayer would eventually become part of a larger exhibition presented at the art institution Overgaden and then circle back into All all all’s program in its second year where Siham was one of the residents.

“All all all is designed as an open-source project,” Klara says. “Everyone is part of shaping what it becomes. The artists are invited to elaborate on frameworks from former projects and in this way, the platform is in constant movement – it is not supposed to coagulate into a fixed identity.”

Economic transparency

But such a format also demands radical transparency. One of All all all‘s more subversive gestures has been the publication of meticulous financial breakdowns of each project via their newsletter.

“Money is often used by larger institutions in subtle ways to keep the smaller spaces in their place,” Klara says, and Sif gives the example of how it can seem very privileged to be offered an exhibition space with rent paid and a yearly budget of 100.000 kr. But in the end, this economy does not go a long way compared to how much content they produced – all of which feeds into the output of the larger institution.

“The default is to tell us that we should be so grateful to get this offer from a bigger institution. But no one is ever going to speak to us or the artists like that. That’s why we need to be specific about how we use our money and what we get done with what we have,” says Klara. “We publish exactly how much we receive in funding, how it’s distributed, and who gets paid what.” This contributes to showing the huge gap in economic funds versus what content is produced between the bigger and smaller art spaces.

“There’s an unspoken consensus in the art world not to talk about money,” she continues. “That silence perpetuates inequity. I’ve been low-key told not to share too much in the past, but I also sense a generational shift now where there is more transparency around economic matters.”

This economic openness serves a dual purpose: it’s a critique of the opaque financial structures of established art institutions but also a gesture of solidarity directed to the field of emerging artists where precarity is the default.

I ask whether they received any responses to this act from the institution, and the two curators point out that it was more of a non-response: there never came another open call at Gl. Strand after their yearlong residency ended.

“It was a clear message,” Sif says. “However, a new director was appointed in this period, and they needed to create a new identity. But it still says something about how the larger institutions often fear letting in alternative projects that challenge them too deeply.”

Klara reflects, “Maybe it just wasn’t a priority anymore. But still—it shows that our way of working wasn’t seen as something worth continuing.”

Diverse processualities

Artist feedback, however, has been overwhelmingly positive: “Regarding the openness around money, the artists definitely felt seen. It shows a precarious reality that is so recognizable from their perspective,” Klara says.

The curatorial challenge to open the process to the audience was also productive, but this part was more ambivalent:

“It was draining for the artists to expose their process in this way,” Klara says. “Looking back, I am aware of this. Some projects were very personal, even painful. Framing the curatorial approach as care-based and then setting up this very vulnerable format can seem contradictory. We constantly had to ask: is this good or bad practice? Are the curatorial tools we’re using genuinely supportive, or are they just another form of pressure?” However, even though it was at times hard for the artists, it was ultimately a rewarding experience for them, the curators emphasize.

Furthermore, ‘processual’ wasn’t a fixed term, and each artist was invited to define what it meant for them. Julie Falk, who had just become a mother and faced major adversities in her life, created a library that she would expand with more books continuously during the exhibition period – a ‘softer’ processuality that fitted her life situation. Another artist, Ihsan Ihsan, used the space as a full working studio, painting several works while the space was open for the public.

For her residency-project, Sidsel Ana Welden sewed an arpillera (patchwork tapestry created by Chilean women, particularly during the Pinochet dictatorship) in solitude. At times she would invite other members of the Chilean diaspora to join her, turning a private and painful practice into a collective act of resistance.

“Sometimes she sat there alone, sometimes with many people,” Klara recalls. “That collective moment gave her something important and nurtured her in an otherwise difficult personal experience of painful memories and loss.”

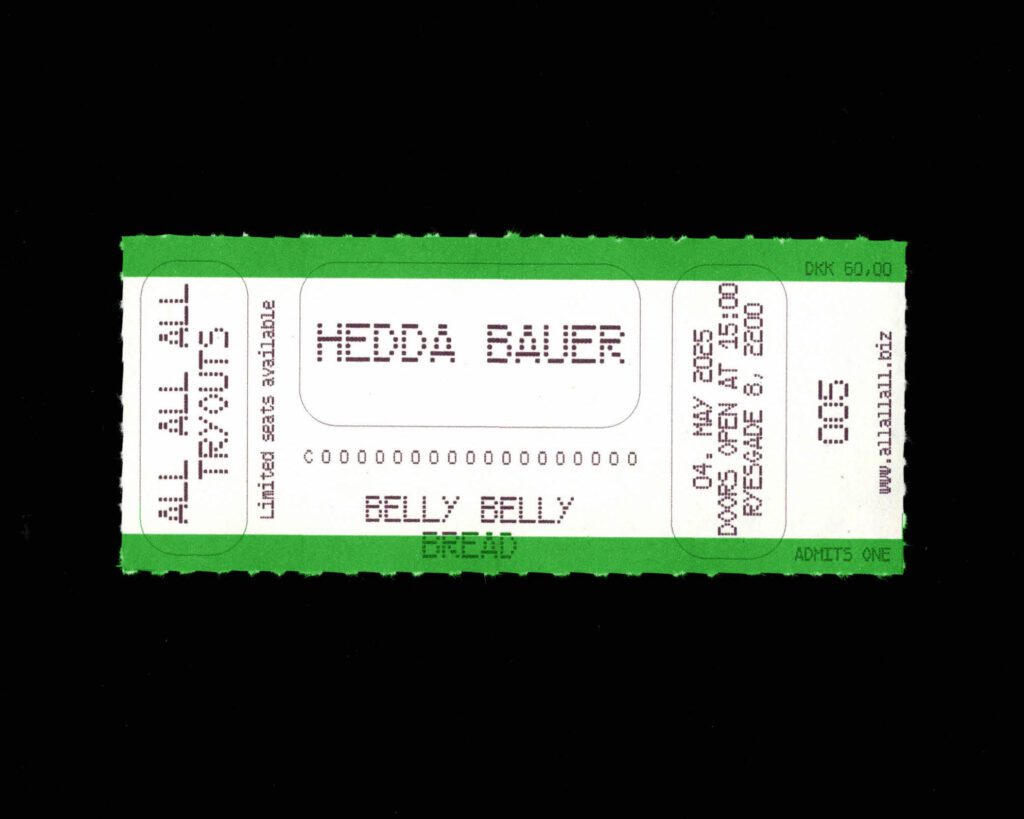

Ticket to Belly Belly Bread by Hedda Bauer

Flipping the hierarchy

During year two of the platform, having cut ties with Gl. Strand and relocated to Nørrebro, All all all introduced Tryouts, a residency-program centered on live formats rather than objects.

“We flipped the hierarchy,” Sif explains. “The live element came first, and the exhibition became a support structure around it, a sort of scenography”.

Artists began using the residency space not just as a studio, but as a home—a place to rehearse, host friends, and build installations over time.

“Some artists even slept over and used the shower in the space,” Sif notes. “It became a site of full immersion where the ethos of All around collaboration and community was further accentuated.”

“But it’s a demanding format,” she adds. “You’re producing both several performances and the environment to support it in the form of an exhibition. The whole self-perception of the fine arts world – regarding concepts for these experimentations and, more importantly, its funding structure – is not set up for this approach at all.”

Sustainability contradictions

With expanded ambitions and more hours put into the live format came greater strain, also for the curators who work full-time on the platform without any salary. In the vein of economic transparency, I ask if it’s not time to show a little (self)care for the curator?

“We do the project development, budgeting and funding. And since our salary is the cost that we can most easily cut out, that’s usually what happens,” Klara says. “That’s the contradiction. We advocate for fair wages and responsible art practice, but we’re then cut out of the budgets ourselves.”

“There’s a double standard at play,” Sif agrees. “We say this work needs to be sustainable for everyone involved, but if we do not take ourselves into account, we will risk burning out and not be able to continue this platform. So, the next step is to start making sure that we can assign a minimal wage to ourselves after everyone else is paid. At the same time, I think it’s important to point out that part of our job as curators is to facilitate the best possible conditions for the artists – not the other way around.”

Looking forward: Gaza Biennale and more

On the 7th of June, All all all is launching a collaboration with the Gaza Biennale which will be the last project of their second year. It is a multi-site exhibition that structurally enacts a reverse version of the Venice biennale: with pavilions representing and supporting Gaza in all the 12 participating countries, paying testament to Palestinian artists during the ongoing genocide and displacement of the Palestinian people.

All all all will curate the Danish pavilion, showing four artists in their space: Jehad Jarbou, Yasmeen Al Daya, Ghanem Al-Din, and Aya Jouha. It is hard to think of a more important exhibition, during a time when Palestine’s cultural heritage is being destroyed, than to create a platform for talking about these atrocities through art. It is also a task that requires alternative working approaches, including making replicas of artworks, since the original ones cannot be transported outside of Gaza. Afterwards, the curators want to take a break to plan for future projects– even if this means not having a permanent space for the time being.

Klara: “All all all is a bag of ideas and practices, not a venue. It will survive even though we do not have a space for a while. This nomadism is also a way to make the platform more sustainable for us. The goal is not to become more rigid, but to stay curious and open—and above all, not to become cynical.”

“It’s about doing more, and showing and talking less,” Sif adds. “Of course, words and objects are important, but we already have plenty of that. So, the doing-part is what we want to double down on in our curatorial practice.”