Performance artist Filip Vest reports from the Performa23 biennial and reflects on this year’s tendencies; mumbles, cries and silences in a festival filled with words, questionable commission choices, sticking to the script and improvising in a world that is burning.

“I don’t understand why people are so obsessed with Nora Turato – doesn’t she just talk and yell a lot?”, a curator asks me in the line to see the Croatian artist Noras Turato perform at Performa23. The day before, someone at Søren Aagaard’s performance had mentioned that “they do talk a lot”. And Performa23 is a biennial filled with words: not only in the packed program of talks, but throughout the diverse series of performances themselves. There are long scripts; appropriated texts; poems; songs; descriptions of performances that never took place.

Performed at the New York Society for Ethical Culture. Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk. Courtesy the artist

and Performa.

Performa is a biennial for performance art founded in 2004 by the art historian and curator RoseLee Goldberg. For almost twenty years, the festival has explored the role of performance in contemporary art and the wider history of art through commissions of new work by both American and international artists and in talks, exhibitions, videos, and publications.

In the same way that earlier editions took inspiration from Dada and other art historical movements, the program for Performa23 is loosely inspired by the legacy of conceptual art. When I meet her to interview her on the history of Performa and performance art, RoseLee Goldberg explains that it not so much a theme as a “historical anchor.” “Oh, is performance back? But it never went away,” she notes, explaining how performance art has always been integral to the history of art. “It’s critical to Constructivism, it’s critical to Dada, it’s critical to Surrealism, it’s critical to the Bauhaus.” Performa simultaneously reflects on the past whilst looking to the future with commissions of new work (“I want to see something I’ve never seen before,” Goldberg says). In this way, Performa serves as a link between the legacy and the progress of performance art.

While the role played by conceptual art in the curation of Performa this year is not totally clear, it is evident that many of the pieces in Performa23 are very concerned with language. Speech plays a prominent role. In her performance, Nora Turato takes on the role of a form of coach. Barefoot, confident, she steps in, an expression both annoyed and sly on her face, to deliver a manic monolog about self-help and self-realization. “What has prevented you from crushing it?”, she asks before continuing the performance in blocks of text lifted from the internet in the semi-threatening language of self-help coaches and influencers: “You make yourself sick. You are not good for you.” Nora Turato does the same thing as she always does in her performances, “talks and yells” as the curator in the line said. But she has an amazing charisma, that you’re immediately drawn to. Unfortunately, the script never really lifts off, and while I’m listening to Turato’s monologue, I’m thinking about how the disadvantage of working with appropriated text material, is that we know it so well already. In that way, there are no surprises and most of all it feels like being presented to the artist’s research material.

Søren Aagaard’s performance dinner Café Zero – A nomadic smoke and fermentation house with no seasons is another very text-based performance, but here the text has a more mumbling quality. In it, a group of chefs stand in a post-apocalyptic scenography of tie-dyed textiles, produced in collaboration with the Danish designer Anne Sofie Madsen. The chefs prepare a meal while discussing bacteria in a gastronomical and political perspective. One of them speculates that the reason people were so obsessed with making sourdough during the Covid-pandemic was, perhaps, that it was a way to control bacteria – to feel that one could control the virus. The performance is, like Turato’s, filled with words, but also with smells and sound: wet things walloped against each other; hard shells crushed, separated, stirred; a clink, a rattle; the sour smell of ocean and herbs. Finally, the work gets another dimension when we are invited to eat the experimental food. Before serving it, the chefs discuss how the dishes might be presented to the guests when there are no seasons to connect it to. “With the right storytelling, it’ll go fine,” one of them says. In the end of the performance, the storytelling drowns a bit in the audience’s chatter and the chef’s mumbling conversation about bacteria are no longer separable from the noise of the audience talking, munching, gnawing – maybe intentionally.

Browne. Courtesy of the artists and Performa

Storytelling seems to play a role in several of the biennial’s pieces this year. Which stories we tell and don’t tell – and how we tell them. The Canadian artist Marcel Dzama’s performance To Live on the Moon (For Lorca) is loosely based on Federico Garcia Lorca’s never realized script Trip to the Moon from 1929 and is a mix of both live band, big capes, splashing fish, moon people, guitar play, and poetry readings in a story about surrealism and fascism. Dzama’s work unfortunately ends up becoming a nostalgic homage to Lorca, that is not contextualized to the present. The performance also struggles with both wanting to be a film and a performance. Sometimes the performers on the stage do the same things as they do on the film projected behind them and the result just becomes a messy unnecessary repetition. Dzama hasn’t made performance before he was commissioned for Performa23, which is a strategy that Performa has been using several times before. It can seem a bit contradictory to make a biennale that puts the spot-on performance art, and then commission new works by artists, who have never made performances before. In many ways the commissions seem to both be Performa’s strength and weakness. It’s “trust and risk” as RoseLee Goldberg says, but I think it’s also ‘hit and miss’. I can’t help but wonder what the purpose of delegating performances to artists who don’t normally work with performance is – besides giving unpredictable results. When I ask Goldberg about the commissions, she talks about falling in love with an artist’s work, and dreaming about what a live work would look like by that artist. It’s a sentiment I understand, but at the same time, it seems paradoxical that Performa doesn’t use the commissions to instead challenge the big field of artists already working within performance to work in other ways and imagine what something we have never seen might look like. I want to see Nora Turato with a live band, a big cape and a wriggling fish in her hand.

Co-produced by the Federico García Lorca Foundation, Granada. Courtesy the artist and Performa.

Photo: Maria Baranova.

“I’m Marcel Dzama” one of the actors in the beginning of Dzama’s performance announces. Another performer is on their knees, holding the script from where the actor is reading. In the same way, many of the performances at Performa23 operate on a meta-level, pointing at their own production and how they come to life in the meeting with the audience. Another example comes in the play reading by the Iranian artist Nashim Ahmadpour, part of an event by Pages, a bilingual magazine for performing arts in Farsi and English founded in 2004 by the artists Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi. Ahmadpour’s performative reading takes the form of a fictionalized account of the meeting of a jury at an Iranian theatre festival from which several artists ended up withdrawing. On the stage are four performers, one of them Ahmadpour herself, playing the four jury members, one of which, again, is Ahmadpour herself (here played by another performer, shifting the relation between reality and fiction). The stage directions are displayed on a screen behind the performers: “Consider the reading of this text as a performance contract,” we read. Later, it is described how the performers leave the room before re-entering and changing seats, even though it doesn’t happen. Later still, we read how a poster is projected on the screen. But we never get to see it as an audience, much as we can never experience the performances that never took place and must settle for having them retold. As one of the jury members says: “Here we are only concerned with unrealized performances.” Ahmadpour’s performance plays with what is shown and what is not, how something that never happened can be retold. It is, in other words, a performance that almost doesn’t take place about a series of performances that never took place.

Sometimes it all gets a bit too meta, but at the same time the big focus on text and the clear inspiration from theatre at this year’s Performa feels like a breath of fresh air in relation to the Danish art scene, where the ‘theatrical’ is still a swear word in a performance context that still for the most of the time insists on not telling stories, but work with more abstract, durational pieces. At the same time, the big focus on a more classical form of storytelling and narratives, that is at stake in for example Dzama’s piece, can seem weirdly dated in a performance biennale that is interested in showing something new.

It’s interesting to note that many of the performance venues at Performa more resemble theatre venues than visual art venues. There are stages and seating, dimmed lights, muted phones, stillness: something we’re not used to in a visual arts context, where the audience is typically more flaky, entering and leaving spaces, passing through performances. For Performa, it seems to be a strategy. As RoseLee Goldberg tells me: “This is not something where you walk in and you walk out. You come into your seat for an hour, and you think. And then you have a conversation. So I’m setting up a kind of social environment for conversation about what’s going on in culture.” This points to another culture Performa is trying to create in the visual arts world: let’s sit down and engage with performance art in the same way we do in the world of dance and theatre. This feels like a good strategy in an art world, where performances often just become a fun feature at the opening and don’t always get the room, they deserve.

On the contrary here people are standing in long lines to experience performances. Two long queues are going down both ends of Broad Street in Lower Manhattan, when I’m waiting to experience the performance Algorithm ocean true blood moves by Julien Creuzet, the French-Carribean artist who is set to represent France at the Venice Biennale next year. For Performa23 the artist who usually works with film, installation and text has been commissioned to do a performance. The work that has resulted from it is a performance made in collaboration with the Brazilian choreographer Ana Pi and dance students from the famous Alvin Ailey school. The performance takes place in a weird building, that used to house a bank and has a 225-foot-long mural with ships sailing across the wall. The ocean as an image also frames Creuzet’s piece, that explores the collective memory of movement across the Black Atlantic. A group of white clad dancers start to move in the space, making slow boxing movements as if their bodies were underwater. The choreography combines movement material sourced by Creuzet from the internet with historical dances from the Caribbean, that the dancers skillfully switch between as they begin combining the dances with exaggerated facial expressions of grief, joy, gravity, a smirk face and a pantomime selfie. In the other end of the space a big screen plays a 3D-animated film by Creuzet showing flowers dropping to the bottom of the ocean, historical artifacts dancing and floating coffee beans. At times the video and the dancers feel like they’re competing for the attention, but in contrast to Dzama’s superfluous repetition, they supplement each other. Even though Creuzet’s work is more movement-based than the other performances, words also seem to play a big role. From time to time an original song plays from the video with lyrics exploring the zombie as a character in a postcolonial perspective. Throughout the song the word ‘zombie’, that historically has been used as a biopolitical violence against indigenous cultures, takes on new meanings, contradicts itself, is “queered” and reversed and used to describe the people in power instead. Similarly, in one of the verses the word fish changes meaning to poison, because of the similarity of the two words in French. In Creuzet’s work everything seems porous, words change meanings as old and new movements enter into a dialogue about Creuzet’s own heritage and the violent legacy of colonialism. The performance ends with a French song performed live by a performer, that is dressed as a sort of priestess. She ‘reanimates’ the dancers, that are lying on the floor. They become zombies, get up from the ground, start clapping and shaking. “Remember those who lie beneath the ocean,” the priestess says. And the dancers start pointing while dancing, in the same way as the work keeps pointing at different references, movements and words, as if to say “look, look, look,” and “remember.”

Performa.

Other spaces in the festival more resemble the typical visual arts venue, the only difference being that they are filled with chairs. One such is the raw industrial concrete building inside which the Finnish artist Teo Ala-Ruona’s performance Enter Exude takes place. The performance, exploring trans masculinity and cars, takes the shape of a sexy, delirious carwash. But at first, true to Performa23’s flirt with the meta, no car is visible in the space, as one of the performers says: “Imagine a beautiful sportscar in front of you”. They then go on to describe how we’re interacting with this car that isn’t here, while they themselves interact with the audience, touching us gently, toying with my earring, drinking someone’s drink while keeping eye contact. Through the text we’re doing a similar imagination exercise as in Ahmadpour’s reading, but this time it’s the kind of meta nature that is inherent in sexting, the “imagine I’m doing this”, the eternal insufficiency and stupidity of words trying to describe something sexy. Enter Exude playfully balances this tension between the awkward and the serious. “You’re fucking the car,” one performer says, stating the by now obvious and making the audience release a nervous laughter. Are we aroused, are we frightened or are we laughing at the silliness of it all? Maybe we don’t have to worry and just: “Remember to breathe,” as a performer tells us. The performance continues in its own hypnotic tempo, as a real car slowly drives into the space and the three performers become less interested in the audience and put their attention on the car. They start grinding on it, blowing smoke and oil into each other’s mouths, and talking about their dads to a soundtrack mixing techno and cheesy sax. They are like bored horny teenage boys in a parking lot, having an orgy with a car while unpacking their trauma. One of them talks about his dysphoria into a pipe, another one sucks at the other end of the pipe and blows out smoke. The bodies become machines. Speech turn into smoke. Trauma is the fuel. Dad is dead, but the car lives on…

by SAA. Co-presented by the Finnish Cultural Institute New York as part of The Finnish Pavilion Without

Walls. Performers: Raoni Muzho Saleh, Charlie Laban Trier, Teo Ala-Ruona. Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk.. Courtesy the artist and Performa.

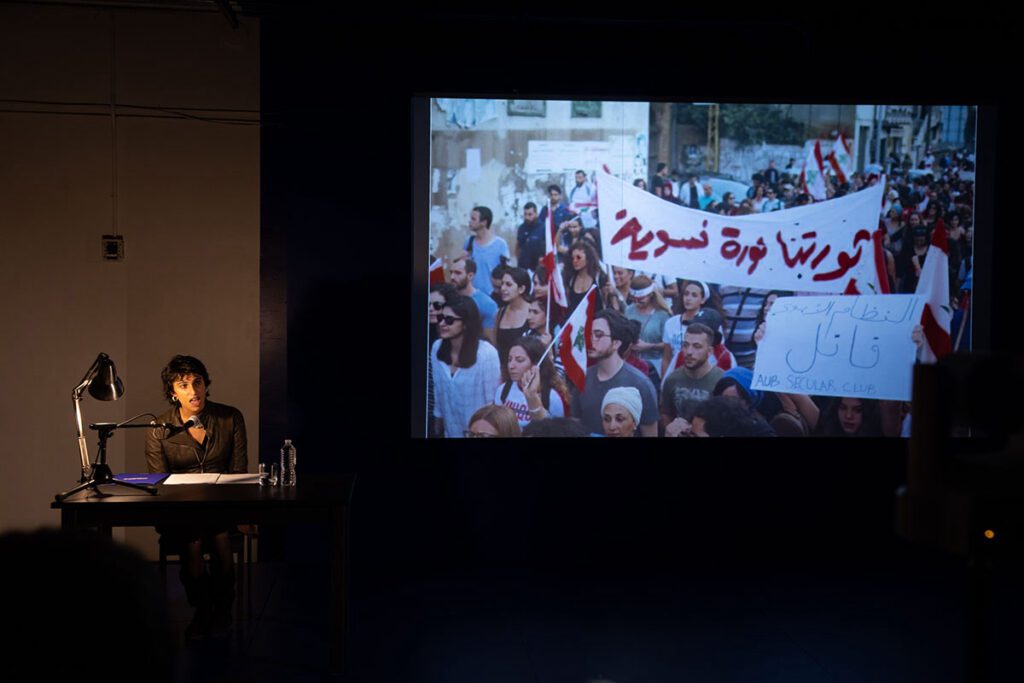

This year, Performa has launched the program Performance and Protes. Unfortunately, it doesn’t receive a lot of attention in the press material. This was the program including both Ahmadpour’s performance and a highly interesting lecture performance by Rabih Mroué about the 2019 protests in Lebanon. Strangely enough, Palestine is not mentioned in any of the communication materials, talks or performances I saw, except for Teo Ala-Ruona’s performance, in which the artist and the performers decided to use their platform to speak out about Gaza. It’s interesting to note how few of the bigger art institutions here have made a statement compared to the number that showed their solidarity with Ukraine. Here in Denmark, at the time of writing, I’ve only seen Overgaden make an official statement. Meanwhile we see how artists in Germany, and other places, have their exhibitions cancelled for posting about Palestine on social media. The institutions still stick to the script. Once again, it’s the artists that have to take the fall.

After the show, Teo Ala-Ruona and the two other performers came in clad in sweatshirts with Palestinian flags and addressed the situation in Gaza, even though they had been told by Performa that they couldn’t. Clearly nervous and with trembling voices, the three performers made a statement about the genocide happening in Palestine now.

It wasn’t part of the script, but when the world burns, sometimes you have to improvise.

And in a biennale filled with words, is it nevertheless the performers’ finishing words, that stay in my body, as a reminder of the power of words, of the importance of talking, yelling, songs and poetry and a reminder to keep using your voice, even though it can at times seem hopeless:

“From the river to the sea. Free, free Palestine.”