RoseLee Goldberg is an art historian and curator based in New York. Goldberg is known for putting performance on the map with her book Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present from 1979 that is still a key text today for teaching performance at universities. She has earlier been a curator at The Kitchen in New York and curated performance programs at MoMA and Guggenheim among other places. In 2004 Goldberg founded Performa, a biennial for performance art in New York. During the last almost 20 years, the festival has explored the role of performance art in the history of art and in contemporary art through commissions of new work of both American and international artists, talks, exhibitions, videos, and publications.

While in New York to experience Performa Biennial 23, I got the opportunity to meet RoseLee Goldberg for a 30 minute interview in her tight schedule back-to-back with other interviews, meetings and performances. We met in the Performa Hub, the lounge space of the Biennale where they present talks and where the visitors of Performa can come and visit all day during the festival to get a break and meet other people. This is the conversation that came out of it, slightly edited for the sake of readability.

Filip Vest [F]: It’s been almost 20 years since you founded Performa. What was the vision? Why did you start this biennial?

RoseLee Goldberg [R]: Why I started Performa? Because New York was getting very boring. The conversation at the time was very much about the marketplace. It was really the beginning of another kind of market-driven excitement in the art world. You know everyone was moving to Chelsea and these giant spaces. So, there was a lot of conversation about that. And the other reason I started it was that I came to New York when it was a very different town, and we all lived nearby and the conversation felt endless, and I wanted that community again. I wanted to create a space where we could discuss ideas and not just how much something costs and what’s going on in the market. And the third reason was to really tell the story of this history that very few people understand: the history of performance art, and the role of performance art in the history of art. I separate those two because I put it inside art history. It’s not on the side of art history. It’s right in the heart of art history. You know, in my book (Performance Art – From Futurism to the Present, 1979), I was trying to link all the times in the Western culture where performance was so important. It’s critical to Constructivism, it’s critical to Dada, it’s critical to Surrealism, it’s critical to The Bauhaus. And explaining how performance art doesn’t go away. It’s always there. People would always say to me: “Oh is performance back?”, but it never went away. People don’t understand how integrated performance is to the history of art. So those were three big reasons. And maybe the fourth big reason was that I really wanted to commission new work for the 21st century. I wanted to see something I had never seen before. Show me something I don’t know. Because sometimes you can know too much. I’ve been looking at performance since the 70s. So, the idea of commissioning new work is very important to the Performa biennale, because we really support the artists, we find the funds, we find the space. It’s not just an artist on their own trying to reach people with their art and ideas.

F: You mention how performance has played a role in art movements such as Dada and Surrealism, and I noticed in the press release that this year’s Performa Biennial 2023 is working around the theme of Conceptual Art, so how does that play a role in the curation?

R: Well, it’s not really a theme. It’s what I call a ‘history anchor’. And in a way it’s been following the chapters of my book. I wanted people to understand this history. It’s very important that they recognize that there’s a lot of intellectual and historical weight we carry. So, for the edition working around Futurism, we did a Futurist dinner based on the Futurist cookbook. We rebuilt a Futurist noise machine for a concert. It’s a form of education. That’s why I sometimes say that Performa is like a museum without walls. It’s like how you can go to an exhibition and then you understand ‘Paris in the 20s’ or something like that. Of course, we can’t show everything, but one of the things we do is that we make a reader. I teach at NYU. So, what we do is, we collect a series of texts, which is a great way to educate the team, and also the artists.

F: Do you also give these readers to the artists for the commissions? Or how does it work?

R: It’s not always connected. They play a role sometimes in the commissions but not always. The commissions are based on what I think is exciting and potentially could be brilliant to do with the time. And if it fits the theme, sometimes it does, sometimes it doesn’t. For example Liz Magic Laser came with some completely different ideas and then she read (Vladimir) Mayakovsky’s essay in our Russian reader and it just completely blew her away. The essay is called ‘Living Newspaper’ and it just gelled for her and she created maybe the best work of her career, where she said ‘the living newspaper’ is our TV station. It’s a brilliant piece that she did in a movie theater incorporating broadcast news interviews with Hillary Clinton and Sarah Palin. It’s just so clever and that work completely changed because of the reader.

F: So that’s also a way to challenge the artists somehow?

R: Yes, and to give them information. So, the readers are exciting to give to the artists, because they read them and come back with ideas. Even Barbara Kruger, I gave her the Dada-reader and the whole language changed about how she wanted to do her work and how we would spread it around the city. And then for the Bauhaus year, photographer and vogue dancer Kia LaBeija took a work by Oskar Schlemmer (German painter, sculptor, designer and choreographer associated with the Bauhaus school) and she made this piece that is so gorgeous, a remake of an Oskar Schlemmer work but in a sort of very New York 21st century way influenced by her photographic and dancing background.

F: That’s also something you’ve been working with throughout all of Performa, commissioning artists to work in a medium they haven’t work in before. What is the idea of that? What do you propose to them?

R: “Will you consider doing a live performance?”

And then we start talking about it. And it takes about two years to get there. I think my reasoning is, I wanna see works that will surprise me. The works of wonder that I’ve never seen before. And what makes me approach the artists is that I see a sort of storytelling. I see an energy. I see something that I think this artist would respond to. It’s like falling in love you can’t always explain it. Why do you see someone on the street and go “ugh”. It’s just about loving the work and thinking “What if I ask this artist to do something live?” And I haven’t been turned down.

F: But I guess it’s also a process of trust from both sides?

R: Totally. I call it ‘total risk, total trust’. It’s a risk for us because they’ve never done performance before. And it’s a risk for the artists because it could totally mess up. But it’s also trust, because if I believe in an artist’s work, I’m sure they will produce something wonderful. And they know we’ll make sure there’s enough support to make it happen in a very special way. So, we act as dramaturgs, as curators. We’re not just sitting back and saying “Here’s the commission, come back in two years.

F: So, you actually have more of a hands-on approach?

R: It’s true. In the best sense. I mean we’re very careful we don’t interfere but there’s a lot of intervention and a lot of insistence that we can take this much further. So, we have a lot of knowledge as producers now and we share and talk about a lot of different things. “What about that film, do you remember that film where …” We’re talking about a lot of different genres as well.

F: What would you say have changed in these past 20 years in the field? And how has Performa changed as an institution?

R: Everything has changed. What happened yesterday. What happened this morning. I think we’re changing all the time. As far as institution we’re always building new ideas. You know we only had a ‘hub’ by 2009, because I said you know we have a small office on 23th street, but we need a public place where people can meet. The whole idea here is that you can come and hang out as long as you want. We’re all here. You can talk to us. You don’t have to make an appointment. So, the whole idea of the hub is that you can be here from noon until 8 and just stick around, absorb the possibilities, and meet people. And then in 2011 I came up with this idea of the ‘Pavilion without Walls’. And that was to say, let’s work not just with the cultural attaché in New York, let’s go to Norway, let’s go to Sweden. Let’s spend time there and understand what’s going on. Or we did Taiwan, South Africa, and Poland. And in each case, first we educate the team, so they become very knowledgeable. And we make a record that’s available for everyone else. Then we do education programs and videos around it. So, we’re really concerned that there’s real knowledge coming out of it. And the other thing I think we’re really good at is that we understand New York. We know how to put the work in the world. Because in New York there’s so much going on. “Why this and not that piece?”. And I think we have a good sense of that.

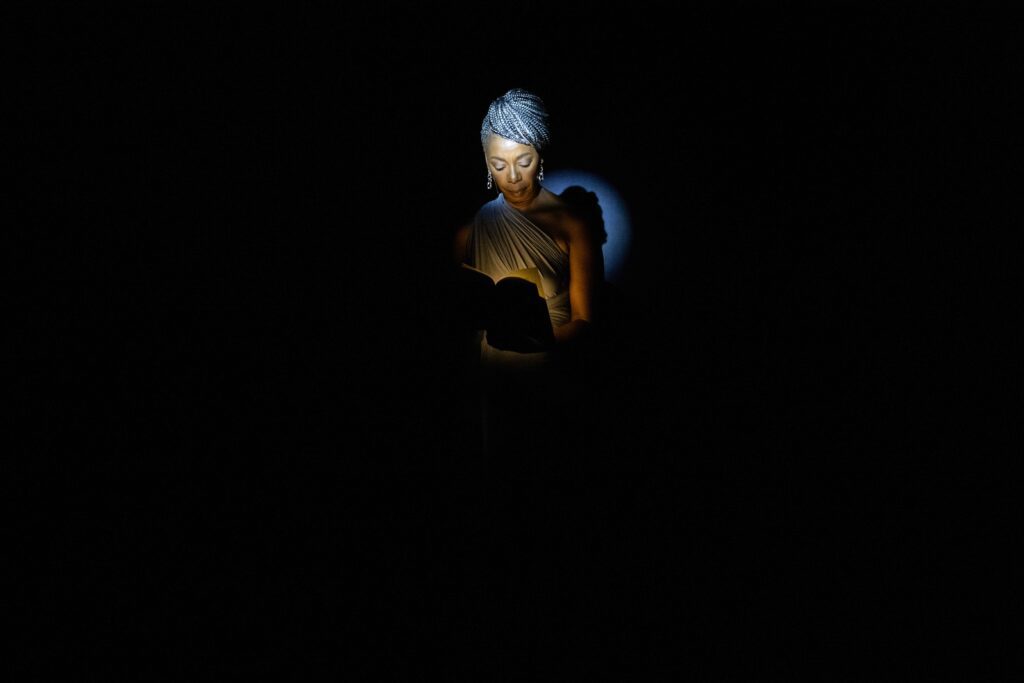

Performa Biennial 2023. Co-produced with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council and presented as part

of The Finnish Pavilion Without Walls. Performers: cove barton, jay beardsley, Magpie, Raymond Pinto,

Isa Spector, Emmi Venna, Kate Williams, Anna Therése Witenberg, and Angel Zinovieff. Photo: Maria

Baranova. Courtesy the artist and Performa.

F: If you had to point to some things that define the performance scene today, what would you say?

R: I think there’s so much going on. I just finished an update to my original book. There’s so many different issues. Each one has its own history. “Why dance in the museum?” What’s that about? Or what’s going on with trans and other bodies and all these ideas. There are so many different areas of study. It’s like painting, you can’t say what’s going on in painting right now. Painting where? Ghana? India? Japan? Marketplace? Not marketplace? So, in Performa we’re always paying attention to everything. We don’t just look at performance, we do architecture, we do dance, we do film.

F: What are some of the most pressing questions to you right now as a curator?

R: Where the energy is. I think it’s very hard to get people to focus on strong ideas. I think there’s a lot of post-covid dissipation. I think people are still recovering from covid even if they don’t realize it. What’s going on in the world’s pretty frightening. All of these are the same issues we’re all upset about. Climate change, gender politics, conservatism. All those different ways of looking at the world. We’re all reading the paper every day and giving the news and trying to understand our relationship to media. Trying to keep the good and change the bad. Make a better world.

F: And what role can performance art play in that?

R: Performance art plays a very important role, more and more. First we’ve now established a base for the history, so finally people are understanding a little bit more. It’s like the avantgarde of the art world, you can experiment and do things outside the marketplace. And with all the new technology it’s gonna be the only place that is personal. You’re talking to somebody, you’re not at home looking online. The fact is that it’s live. I designed that also in a very special way. This is not something where you walk in, and you walk out. You come in, your sit for an hour, and you think. And then you have a conversation. So, I’m setting up a kind of social environment for conversation about what’s going on in culture.

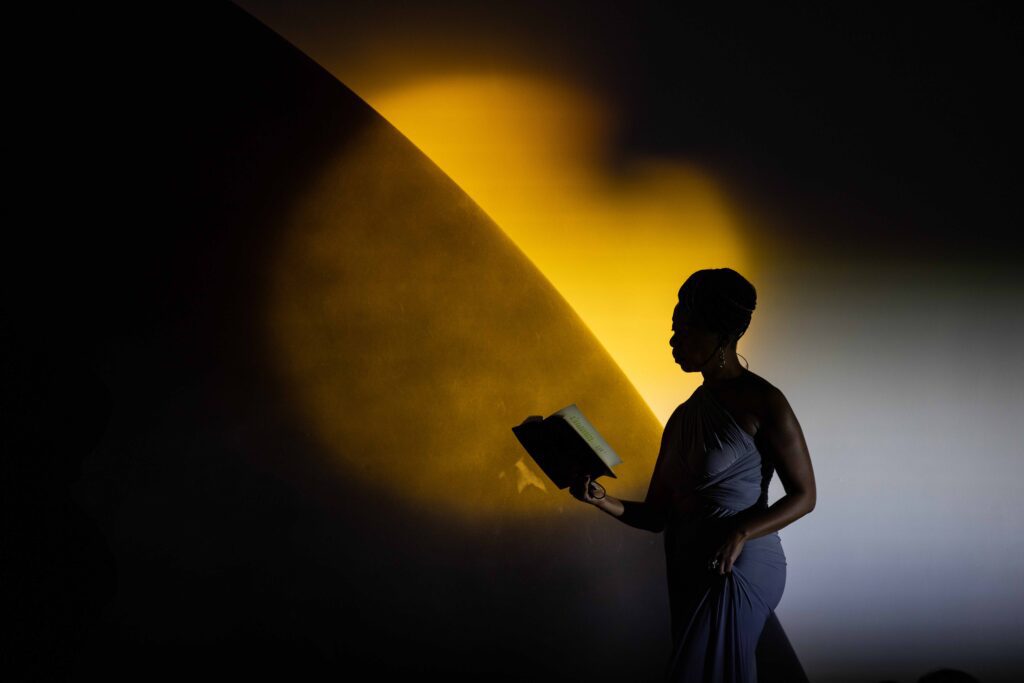

for the Performa Biennial 2023, November 1-19. Co-produced with the Solomon R. Guggenheim

Museum, New York. Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk. Courtesy the artist and Performa.

F: Now you mention this idea of being outside the marketplace, which made me think about how performance art has this history of trying to escape the commodification of art, but then eventually got commodified. And something that I think about a lot as a performance artist is how can you even work anti-capitalist within the art system? What are your thoughts about this?

R: You work that way because that’s who you are. There are some realities that you’re going to have to figure out as you go along. Like how you support yourself. How do you make something work. In any situation even the most radical, anti-capitalist situation you still have to find an intelligent way to make the work in the public realm – and have the public pay attention. There’s a wonderful aphorism by Jenny Holzer about how to take what’s most obvious in society and use it to make new ideas and realities. I guess what’s most obvious in this society is money. Of course, there’s not one solution. Every artist has approached it differently. It takes a lot of courage. You have to reinvent it all the time.

F: The history of performance art has always been tightly interwoven with the history of dance and theater, and today it seems like the boundaries between them are getting even more fluid. What does it matter when we call it one thing or another?

R: I don’t think it matters. Well, it does matter in term of context. Being in the art world is a very specific world to be in, and it’s a world where you often don’t instantly understand everything, but that’s okay because you’ll find a way. But again, history shows us in the 20th century some of the most interesting periods are when people from different disciplines are working together. So, futurism, Dada, Russian Constructivism, it’s all about groups of people working together from very different disciplines. You know Bauhaus was one dancer, one painter, one furniture designer, one musician, one poet. The most exciting times in the last hundred years are moments when there’s a big crossover between the filmmaker, the writer, the dancer, Judson Church, all those things. I think that is the nature of art history. Somehow museums and academics separate it, but the reality is that the life of the artist is in a way to be integrated with a lot of different disciplines. I think it’s more the way it’s recorded that separates them.

for the Performa Biennial 2023, November 1-19. Co-produced with the Solomon R. Guggenheim

Museum, New York. Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk. Courtesy the artist and Performa.

F: What are some of the things you have learned from making Performa?

R: I think it’s the richness of working with all the people we work with, including our board, which is necessary for a non-profit. Even starting a board. It’s a privilege who you can have conversations with. It’s kind of amazing all these relations, all these years of history. I think it is the access to so many different minds and people and how to bring that all together. Talking to you now. It’s a wonderful way to be in every day. And to put a team together that can realize ideas. You can have an idea in the morning and by the afternoon it’s “Okay let’s do it!”. That’s the flexibility of performance. We want to make a movie tomorrow, let’s make a movie. We want to make books, we’ll make books. If we want to make a hub, we’ll make a hub. We have a tight group that makes ideas happen. That’s what keeps me excited.

F: Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts.