Chloe Chignell is a dancer and choreographer based in Brussels working across text, choreography and publishing. In 2019 she opened rile* a bookshop and project space for practices moving between publication and performance, with Sven Dehens. Her most recent work Poems and Other Emergencies premiered at Batard Festival Brussels 2020.

I was first introduced to Chloe Chignell, because of common interests in literature, artist books and choreography, which in Chignell´s case comes to fruition both in her own work as well as curating and running a multifaceted art space. These modalities function as containers for different movements. When researching rile* as well as Chignell´s own practice, I was intrigued and fascinated by the way it both opened up new perspectives for me on expanded choreography.

Karin Hald [KH]:

Your latest work is an artist book called The complete text would be insufferable. How would you describe this work and from what state of mind and body did the work come into being?

Chloe Chignell [CC]:

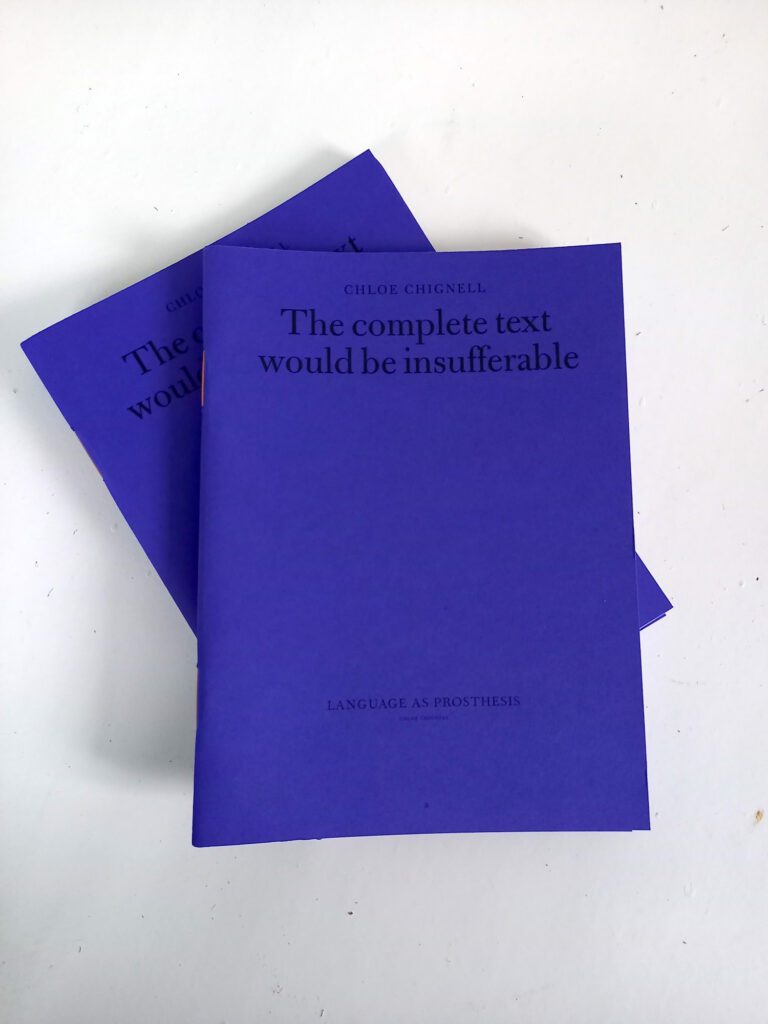

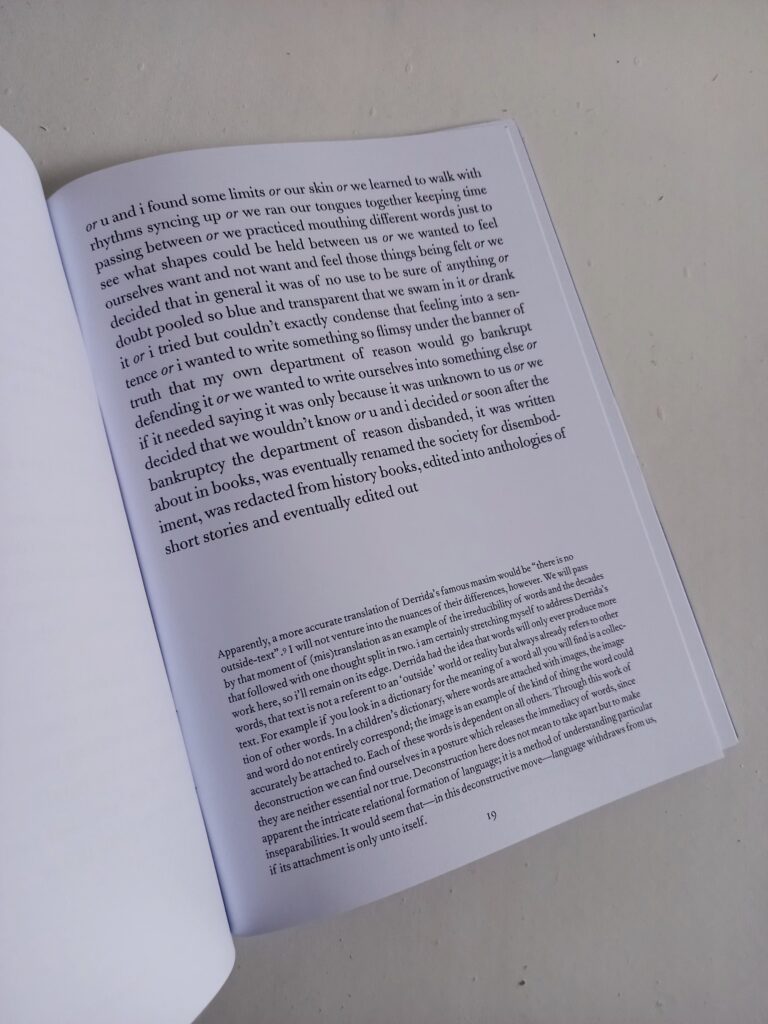

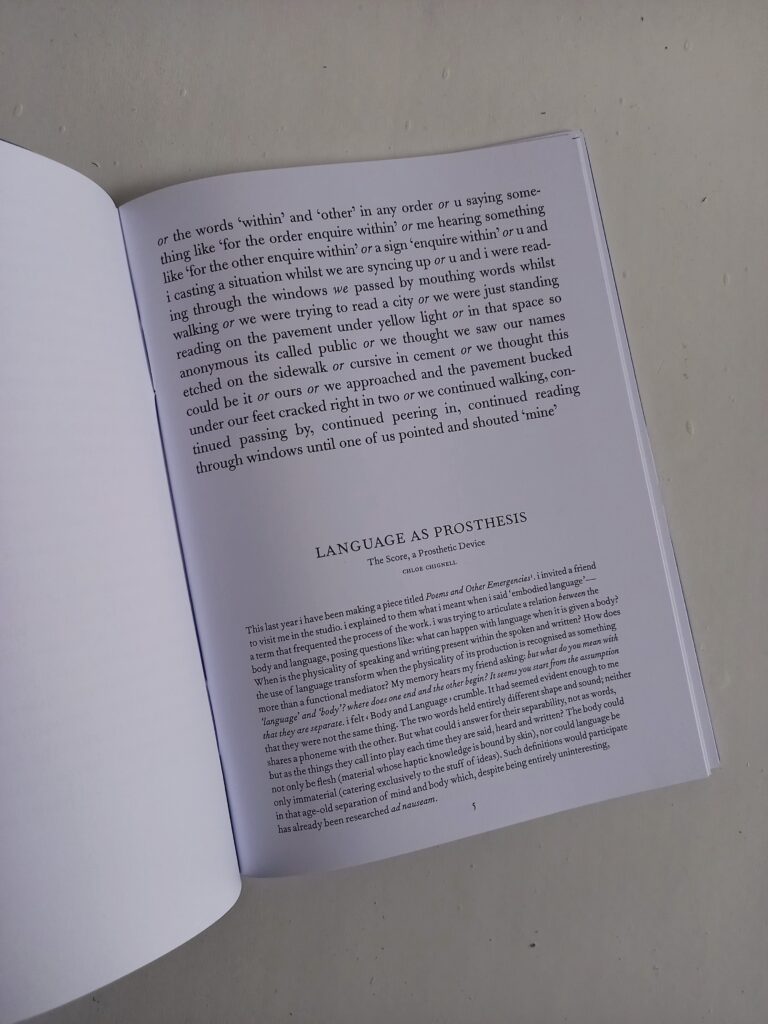

The complete text would be insufferable, is a publication that was made in the context of my end presentation at a.pass – a post-master’s program in Brussels, although the texts within it were written without the intention to be published together. The publication hosts two different texts in parallel, one of the same name, and an essay titled Language As Prosthesis. The Complete Text Would Be Insufferable, a long prose poem, started in the beginning of the first lockdown in Brussels, around May 2020. I had recently premiered Poems and Other Emergencies—a piece that’s interested in practices of description and narration, investing in language as a body building technology—and I wanted to keep thinking along with that work, so I started writing. Given my desire to practice description and the intense interiority and domesticity of that particular moment, it became a lot about the failure of language. Its failure to adequately capture, and the way that failure compels more language. The poem uses Or as its main syntactic device, working through sequences of association so the object in question—be it a feeling, a situation or relation—is defined not only by its own description but the or’s associative leaps. I think writing the text allowed me to play out a kind of horror of interiority, the text, and its recursivity, producing a kind of eternal inside, words sticking onto words, onto words. Which is probably what I was feeling and thinking a lot about during that first lockdown, when we had no idea of the scale, duration or effect that isolation and distancing measures would have on us. In saying that, the text is also not at all about covid-19, nor isolation. It’s interested in processes of attachment and failures of attachment. The second text in the publication, Language as Prosthesis, was written after the poem. I felt that I needed to go back to Poems and Other Emergencies and try to articulate the operative interest within the work, in order to take it somewhere else. I was reading a lot of Paul B. Preciado at the time and was really into his concept of the biotext. It really spoke to a lot of the ways I was thinking and working with the in/separablity of language and body. So I started writing, bending some of his concepts, to test out what could be thought of, if we were to understand language as a prosthetic device – something that attaches to the body, changes its configuration, its legibility, its capacity. And thinking of this prosthetic relation through choreography and the representational apparatus of the theatre. I think there is still a lot of work to do on this idea, and I’m not yet certain on which level of practice one can apply it—but it was an attempt to bring something out of Poems and Other Emergencies. And, I was really excited to write a more academic text, with its form and style—I think by that point (throughout the summer and fall of 2020) any kind of structure and formal stability felt like a luxury.

KH:

In relation to the or which (un)ties the sentences together in the long prose poem, I think it’s generous and interesting that when reading The complete text would be insufferable there are several ways of approaching the actual reading of the work, where I as reader am activated in different ways:

One reading could be reading the poem front to cover, after that the more theoretical text which is situated on the lower half of the pages, another option is to constantly jump between the two very different modalities, making me both confused and intrigued. This makes me think of choreography: how to move in time and space within a text. You yourself mention choreography early on in the work, writing: “could choreography facilitate strategies for (re)writing that living textual body?” It is as if you question language, yet think of choreography as something you are more sure of, which makes me want to ask: what is choreography to you?

CC:

I like the idea of the or as something which (un)ties the phrases within the poem. I haven’t used that formulation myself, but I think it resonates with what I was trying to do structurally. The or proposes a kind of antagonistic relation, it acts as if each subsequent phrase is an alternative, as if each phrase is rewriting the one prior, but it doesn’t entirely erase or negate the previous one. I think this kind of relation, that of non- or un-relation, also functions to connect the two texts across the page. They work in parallel and formally mimic the way a text and its footnotes are laid out, but they don’t function precisely like that. It’s up to the reader to navigate the space in between them and to find the attachments that their sense making requires or enjoys. As a reader, I love when a text leaves gaps that ask my own reading to collaborate on the syntax, on the ways that different parts of a work cohere. It also shakes up the linearity of a text and the repetition of left to right down the page. The movement across the page becomes a little different, and maybe that shift can cause a minor change in how we read as well.

As for choreography, I’ve been asked similar questions before: what is choreography? What is choreographic writing? What does it mean for a book or any other published text to be considered choreography? And to be honest I have never found a satisfying answer, but I do like to think about the questions. It might be a slightly oblique answer but: I don’t think I know what choreography is, and that’s probably why I keep working with and within it. I guess my work comes through a variety of different forms, and it feels relevant for me to think of them taking place within choreography. I don’t think it’s because of anything essential to what choreography is, but it’s more of a context for the work to be thought and to happen. To place my text work within choreography, is to place it in a community of artists, a history and a discourse more than relate it to a certain expected form. —And, in my experience there is a lot of language involved in choreography and dance practices, even if it’s not the outcome of a work, we often use both oral and written language in the development and transmission of more bodily material. So, I would think that there is an inherent, or even unavoidable, mediation between language and body within dance. You don’t have to go outside the discipline to find language, and I’m interested in finding forms to share that language.

KH:

I am thinking a lot about performance, live art and dance´s liveness and lack thereof in the times we have just left, by which I mean the first and second wave of covid-19. But liveness is also something which has been brought into question by the increase of SoMe, or at least very different modalities of liveness has been brought into play to a much higher degree. There are definitely benefits: people who for different reasons could not attend a physical event, have been given more opportunity to be part of many different communities. On the other hand, the physicality of being bodies together has also proven to be invaluable for our mental health.

Professor in theater and performance Peggy Phelan would argue that a performance is only a performance as long as it takes place in its physical form, live. Even documentation of performance is something completely different and the politics of representation today are fraught. It’s interesting to turn to writing and the making of books, when faced with the lack of gathering in a physical space – books can (perhaps) be more democratic in their shareability.

Now that restrictions are not so severe, would you then like to make The complete text would be insufferable into a live performance, or is it a work which is satisfied in its current form? Has it changed your practice in general living through the pandemic?

CC:

I think the different ways that a book and a dance piece ‘perform’ has been an interest for me even before the pandemic (before bodies in proximity was deemed dangerous). When I first started to publish my text work, it was terrifying that it could circulate without my body, or without my performing it. The cut between the author and the work felt so severe and so much more real—the object of the book stands outside the body of the author. Having been trained in choreography and dance, and making dance performances that I myself would perform, I hadn’t experienced this same cut or separation before. With dance, the work keeps needing you to give it a body. I guess it’s an obvious thought, but it is something that I often think about, that different capacities for access, distribution and embodiment are made possible through different means of publication. In this sense The complete text would be insufferable is definitely a book, and it performs itself in collaboration with each reader. Of course, the reader picks it up, puts it down and decides on their own physical environment for reading. But I would be hesitant to say that it’s not live, or maybe I could say: it’s not not live? Most often, time is inside of a dance performance, and with other media—films, books, etc.—the time is both inside and outside of the work.

I think I have thought about the question of liveness more in relation to attention. Something I really missed during the pandemic was situations for collective focused attention, the kind often found in theatres. Maybe it’s too romantic to put it like this, but I do find there is something heightened, even electric, in the vibe of a large group of un-distracted people. Of course, this kind of collective attention is by no means exclusive to the theatre, but it was during the pandemic that I realized I found that there. There have been quite a few different mediums interfacing performance during the pandemic, but I don’t know if that has made performances less live, or if we are just not yet good at producing the conditions of attention for those interfaces. That being said, there was a certain point during the last year that I needed off screen experiences.

KH:

I really like when “obvious” thoughts, as you mentioned, are noticed and given attention, especially when writing, as I feel that gives them the gravity of time and makes me be able to linger with them and return again and again (also an obvious thought!).

In relation to ”collective focused attention” as you just mentioned in relation to theater – I want to know more on your thinking on both the work and space of rile* – how that forms your practice and impacts your practice as a dancer and writer. But I especially also want to ask you about queerness and queering: You mentioned Paul B. Preciado earlier and his notions on biotext from his work Countersexual Manifesto. I know that you made a bootleg version of Monique Wittig´s (who is known for her thinking on gender as a construct) English translations which you read front to cover in a group reading at Lesbiannale Lesbian Arts Festival at rile*. In The complete text would be insufferable there is also a focus on pronouns and the use and play of those. When I visited rile* I thought about how strategies and notions of queerness seem to beautifully seep through the selections of books as well as the program you and Dehens curate. How does queerness manifest in its wonderful slippery changeability for you?

CC:

I would think of queerness as a practice (rather than as an identity marker) of not yet knowing but trying anyway (to follow up on that thought I would recommend Jack Halberstam – the author of The Queer Art of Failure). I feel a lot of affinity with authors who identify as queer both in their life and in their work, Preciado and Wittig have been huge influences not only conceptually but quite materially, I continue learning how to write through reading their work. I guess it’s something about the potential for disruption and invention that queer work is so ripe with—those being the two parts of the process of not yet knowing and trying anyway. I find this disruption and invention often in literature and choreography, where I show up thinking that I have some knowledge or tools to comprehend the thing and that knowledge falls short, and I realize I don’t yet know how to comprehend it, don’t know what to do with it, nor, how to position myself in relation to it, and that instability is exciting. When I encounter writing or performances that go beyond forms of legibility, or particular logics, that I am familiar with, I have to figure out how to relate to them and I find that work so rich. rile*, which I curate together with Sven Dehens, is a really important project for me. Something that is unique about rile* is that it’s a continuous project, it doesn’t have temporary periods of work and gaps between like alot of my performance work is structured, and because of that consistency it has enabled me to find a certain home or community that I can work alongside. I feel lucky that through rile* I have met, read and worked with so many different artists that have challenged and changed my thinking. rile* definitely hosts a lot of queer work both in the books and the program. I think it’s precisely because of its inventive capacity, both in content and form. The most exciting writers are bending and reworking the things we think we know. Poetry can do this in a very obvious way on the level of language; it can produce a syntax that is not formally correct in order to give form to another kind of sense.

Thank you.