Sara Gebran is a Venezuelan dancer and choreographer based in Copenhagen. Her work is in her own words situated within performance art, exploring media such as video, photography, sound, architecture, radio, and text, mediated by the dancing body, present or not. She has been studying how power is enacted and forms of collective empowerment, through her performances, teaching and writing, specifically with the projects developed in refugee camps in the West Bank Vertical Exile and Vertical Gardening (2009-2011), also while being the director of the education in Choreography at the Danish National School of Performing Arts (2012-16), and the last 5 years, through performances, lectures, teaching and book publications.

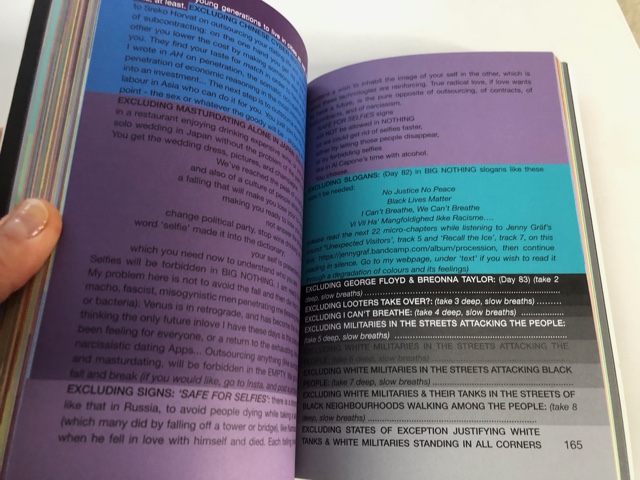

In December 2021 Gebran released the book Quantum Society, which consists of 550 micro-chapters. Quantum Society is easily recognized as a book, but also as performance and body, all at the same time. While starting the interview, I have not yet finished the book entirety yet. Normally this would most likely be seen as impolite – an interviewer who has not read the work from front to cover – but in this instance, I find that it’s a work that resists high speed and begs the reader to contemplate, and take the words in, not only by reading them, but also by embodying them. It feels like a book I would get the most out of by reading one micro-chapter a day, thereby using one and half years before finishing it.

The density of the work comes through its multiple layers, where each micro-chapter reflects both on an individual as well as collective strategies and politics, and where Gebran often encourages the reader to use the whole body, by suggesting movements in relation or response to what is written.

To help or perhaps confuse, Gebran has offered both playlists as well as instruction at the beginning of the book, which is divided as ‘colours by emotions’ and ‘emotions by spacing’ and general instructions such as:

ALL CHAPTERS IN THIS BOOK ARE MEANT TO BE SUNG, FOLLOWING THESE INSTRUCTIONS:

LISTEN TO ANY BACKGROUND MELODY YOU LIKE TO HELP YOUR SINGING.

THERE ARE INDICATIONS OF HOW TO SING SOME OF THE MICRO-CHAPTERS BELOW: JUST FOLLOW THEM.

LISTEN TO THE RHYTHM OF A TEXT UNTIL YOU DISCOVER THE WAY THE TEXT LENDS ITSELF TO BE SUNG.

READING IS A FORM OF SINGING, SPECIALLY IF YOU READ A TEXT WITH FULL PLEASURE.

SING ANY TEXT WITHOUT ANY HELP, JUST USE YOUR OWN INTUITION.

KH:

I want to start by asking about genres as this seems to be a main point of departure in Quantum Society. I have thought quite a bit about this myself, always finding myself resisting existing categories. Genres can seem like a two-headed snake and the question I always circle back to, is:

Genre is filled with history, it has a trajectory, which can make it important to know of genre and what has gone before it and you, yet history can be seen as exactly history and not herstory, meaning that history is made up out of those who had the power to speak (men) and be heard in return.

It seems as if you want to connect theoretical knowledge to somatics, to space, to being alive, and yet you also point out early in the book that writing and this more classical style of archiving is important, though maybe redundant, and something which you have taken a long time to come to.

Can you elaborate on how you perceive and resist, feel and dance genre in your thinking, work, praxis, life?

SG:

First, I am glad to read your understanding of my writing, of some of the layers and layers the text is informed by, a history of genre exclusion, of obsessive classification, categorization, and archiving, to control knowledge, to define the world and its complexity. Thank you for your sharp interpretation…

I will start by saying that the life and praxis of an artist is impossible to separate (I think perhaps this goes for everyone working in the neoliberal capitalist system around the world, not just artists).

As a woman, I have always been concerned with the ways male privilege is transferred within family traditions, to all aspects of life, globally – this precedes my entry to feminist studies. Experiences informed by living in Venezuela (where I was born), Lebanon (my parents are Lebanese), Denmark, Sweden, and Portugal.

The way I decided to strengthen mine and our womanhood since the start of my artistic career in the 90s, has been by mainly inviting women in the choreographic and dancing processes of work. Dance is strongly dominated by women, numerically speaking, yet, we hear mostly of men. This is positively and slowly shifting since ‘Me too’ and new feminist movements, though perhaps too slow? We face strong resistance by those who wish their privilege intact.

Judith Butler writes in Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street, that if we don’t appear in the public space, we don’t exist, like the prisoners, the sick, the refugees… I began thinking that naming is a great tool to make things and people appear, exist, be visible, and be reflected in the eyes of others. In writing publications I had considered and practiced ways to name and reference women mainly, and those coming from the periphery (non-Western). In the publication Quantum Society, there are some examples of naming. The book can be partly read while listening to a soundtrack, through a QR playlist consisting of mostly female electronic composers from all over the world, not just the Western parts of the world. Finding them was not an easy task. The first question was, where are they named, archived? Algorithms are constructed through the same history of racist and anti feminist discriminatory practices by the same men writing it. See for example the findings of computer scientist Joy Buolamwini in the documentary film Coded Bias.

We have a great responsibility to insist on finding ways to support each other, naming each other on public platforms, online and physically. I have few feminist male friends, appropriating the knowledge of women, without naming them since no one is ‘checking’, policing them. We need to build up an ethic of being, of referencing, of naming, to appear, especially in Denmark where white male privilege is at the edge, the competition, and fear of losing privileges, mixed up with the speed of our life, results in new forms of mining knowledge, a neo-colonization of knowledge.

Knowledge belongs to the collective, so we might need to apply the genre form of ‘They’ and ‘We’ in all our forms of communication, if we wish to slow down these forms of appropriation of knowledge, the new plagiarism which the era of internet had generated. These must be combined with ‘naming’, referencing, where our knowledge comes from. There is a lot to say about this…

Basically, I am trying to propose radical practices of self-support and ‘selves-support’, so that we (women) can be pressing harder on the glass ceiling, until a break is produced in the system.

Language is knowledge, so imagine the incredible power inherent in publishing? I have written some lines about that on pages 82-83 and other chapters in this publication, while insisting the reader to refer to me when using my practice… In teaching art students I also insist on the ethics of the practice of referencing. When I ask artists and students if they refer to other artists who have inspired their work, most of the time the answer is no, in shame to reveal their sources, ‘diminishing’ their own geniality. The idea of the hero artists is still inflicting our practice, by the same history.

KH:

In terms of coming into existence, when it comes to ‘public space’, I would like to add that one of my favorite texts on this is Sick Woman Theory by queer witch, artist and musician Johanna Hedva. In this text Hedva goes up against the notion of public space and being political, as posed by Hannah Arendt.

Hedva criticizes Arendt ́s definition of the political as Arendt believes one can only be political by entering the ‘public’. Hedva offers a queer critiquing on what we perceive as public space and the idea that public space is more inclusive than other spaces. Hedva emphasizes that if being present in public is what is required to be political, then many people can be deemed a-political – simply because they are not physically able to get their bodies into the street. Hedva also uses Judith Butler to think and criticize Arendt as to what constitutes as public in her lecture Vulnerability and resistance. As they write “Arendt failed to account for who is allowed into the public space, of who’s in charge of the public. Or, more specifically, who’s in charge of who gets in.”

I would state that the private is political, even when taking it public. In this regard, literature and artist books become relevant, as they offer other (slightly) more democratic modes of distribution than a body or a physical exhibition can offer, as they are limited to only one space at a time. To think how work can be distributed and how this can change, a/effect and translate the work is highly relevant today, not least in regard to the internet. What is the difference between an analogue public space in relation to online public space, and how can we best distribute knowledge, also in a way that is welcoming to those to previously have felt excluded?

When reading Quantum Society I think about how art and discourse around art and public space calls for thinking around a transformed empathic unsettlement (Dominick LaCapra´s term), intersectionality and de-colonial thinking: how can an artwork be understandable and recognizable and not least applicable to different art scenes around the world, thereby creating new connections. Which leads me to think of a “We” as you mentioned. The “We” – the collective – emphasizing quoting each other.

How do we move towards a generous, emphatic, openhearted “we”, while still maintaining the principles of intersectional feminism, how to connect collectively, while honoring and remembering each other’s different circumstances, when it comes to class, gender, race, as not to fall into the capitalistic, patriarchal notion of the “universal”, which really just means a white, heterosexual, middle class, cis man?

SG:

I agree. Hedva made a great contribution revising what Arendt missed, the private is public too, more evident today with digital media devices and platforms.

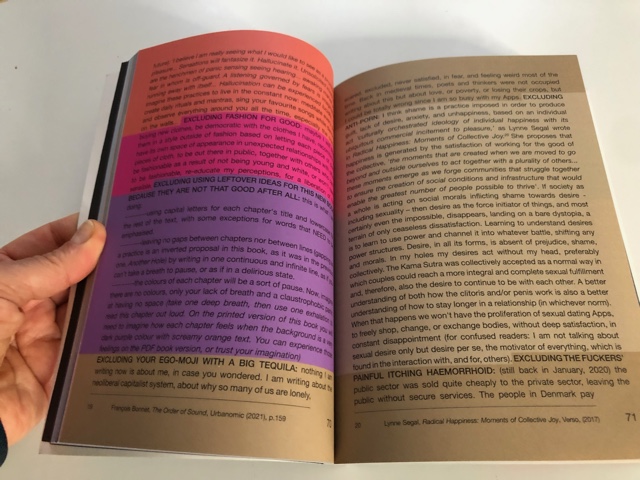

And yes, books are such amazing spaces to be, handle, challenge, define, give access to and share. My interest is in books as spaces to act within, develop knowledge, develop one’s own artistic practices, and make visible the practices of others – collectivizing knowledge – and it is influenced by many things. For example the text On other spaces, Heterotopias by Foucault, and my studies on quantum physics (entanglements, multiverses, parallel universes: rooms within rooms), my background as urban planner and architect, and historical events where I felt the impossibility to access spaces to work, rehearse, and perform. This happened in Stockholm through 2005-2012, leading me to initiate the project Maximum Spaces with a collective of artists, an online booking system offering free entry to rehearsal and performing spaces in Stockholm. A situation that is now worse in Copenhagen…

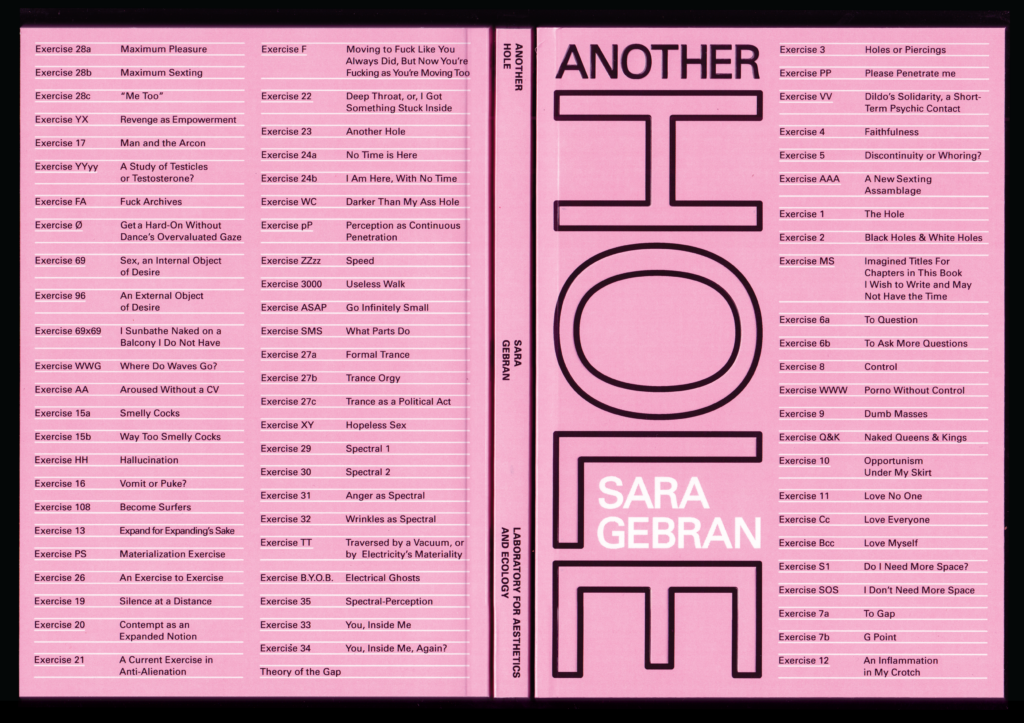

When Sergej Prista talked about ‘Self-instituting’ in a lecture at the ‘Conference Reflection’ in 2015, I organized when I was head of Choreography at Den Danske Scenekunstskole, it gave me hope, about how to think of knowledge, how to produce it, institute it in times when ‘representation’ was/is and will continuously be dead, unless we do something about it. Instituting our own knowledge is radical, I thought. Another Hole, my first publication, was a self-empathic project (to myself primarily and others like me), giving myself the space I need, which I couldn’t find anywhere else. This apparently produced something new, given the interest and comments of so many artists.

Books can be platforms for self-instituting knowledge. I treat them as production venues, stages for self curation and curating others outside the canonic curation exercised at the institutional level all around (eternally wishing for VIP entry). “Choreographic-publications”, is a term I give to writing books using choreographic strategies and tools, considering the page as new spaces for the production of artistic practices, as a stage, as a venue and as a public arena for collective self-governance, with new modes of dissemination, production and transmission, with another type of duration and exchange, crossing all possible borders.

The reader is to be treated with care if we want to practice inclusion. How do we speak to those who do not have enough access to knowledge, people from other parts of the world that are less privileged? I don’t want to reduce our language to a simplistic, popular, fast and perhaps commercial standard. Complexity could be expressed in simpler manners. Language is power, books are a powerful medium to exercise power. The problem with power is the misuse of it, and we do that all the time, all around.

When we access power, we need to remind ourselves to share it, circulate it, rotate it. So that everyone is included. This is why I wrote my two publications like I did, mixing genres, as speculative writing. I addressed the reader with knowledge equal to mine, without explaining or editing things for them, so the reader could also be a translator.

The knowledge of academia is always above anyone else’s, especially practitioners. There is so much work to do against trendy ways of speaking by name-dropping the knowledge of academics (I am not referring to you here, I think you are using this knowledge in a political way, read below). So many original voices are deemed by the power of academia shadowing individuals, especially art students in academic institutions. Professional artists are trying to fit into the institutional needs, confirming the current fashion, instead of one’s own artistic values. Like screenwriter Paul Javel in Jean-Luc Godard film Contempt, giving up integrity on the demands of the film producer, ‘prostituting himself’. I wrote two chapters about contempt in my first book Another Hole: “Exercise 19: Silence at a Distance” p. 89, and “Exercise 20: Contempt as an expanded notion” p. 91, a sort of denunciation of our contemporary cultural decadence and decay.

In my two publications, I practice ‘my’ knowledge, recomposing all ‘I’ know, which does not belong to me, but to us, the past, present and future, decolonized. We have to make an effort to write on behalf of those who couldn’t write their knowledge, the indigenous, our grandparents, the refugees, etc. When writing, it’s possible to reach those voices. We just need to tune more within, mediate for them, as mediums.

In order to prove our own worth, our own knowledge we don’t need to speak through name-dropping literature and philosophy, but refer to them. Our worth is in recomposing the knowledge we already have acquired, digested, lived, experimented, experienced (keep in mind this knowledge belongs to the past, present and future) and we should not let that be diminished by the institutionalized academia suppressing on us (the ‘us’ interested in theories, and working between theory and practice).

We are theorists and we are practitioners, who from our practices can theorize. Our knowledge is as valuable as any academic knowledge or even more, since it’s based on practices. Hence our unique power. That is why I decided to write theories to self certify my own knowledge, as the Theory of the Gap in the book Another Hole, including 75 practices. In the recent book Quantum Society I wrote three theories: Social Intimacy, Quantic Dance and Quantum Society (see the last 13 micro-chapters of the book) and 550 practices.

As a practitioner and lover of theories and literature, I give myself the right to theorize, and institute that information on the pages of a publication for others to continue with me. These publications have been such self-empowering projects. I’m thinking of doing an open online academy, an alternative school for all kinds of people, to help them institute their own knowledge. I hope I understood Sergej’s point with what he meant by self-instituting. I never asked him, I will do it tomorrow. In case I misunderstood him, then I am thankful this led me to where I am now…

I think you are already practicing modes of challenging intersectional feminism, in naming, making visible by seeing who is there, bringing people out of the private to the public. When people appear, a collectivizing process begins. By ‘reaching out’ to women we don’t know, an empathic transformation begins. When acting out curiosity, searching for people, what they do, connecting with them and using time to do so – it is so rare in these overwhelming times without any real time, which the covid crisis augmented. I could say, to be curious and act that out in modes you wish, as you are doing now for example when interviewing me, is acting in concert, making the private public, also interviewing Chloe Chignell and Mette Edvardsen, the past two interviews in this series on expanded choreography, though they are pretty well known. I am thankful to you for reaching out to me, for being curious, for taking the time to do this, a time that is not always there.

Thank you.