SETTING THE FRAME

I made my way through Copenhagen to Refshaleøen, where a two-day seminar on intersectional feminism was taking place. The location, a warehouse in a backyard alley, which required thorough instructions, became a metaphor that indicates the status and position of the conversations we were about to have: it might still take place in the outskirts of both the city and the discourse in the overall art scene, but it exists and has a force of its own. I have been longing for this kind of conversation to take place in Copenhagen, but also in a Scandinavian, as the event was supported by Nordic Culture Point, and therefore I was excited, curious and happy, when I entered the space, where the sun was shining through the large windows, greeting us with a bit of sunrays in the dark fall.

The framework for PERSPECTIVES ON is a collaboration between UrbanApa and HAUT as part of BRIDGES 2022.

BRIDGES is a new Nordic collaboration project that aims to strengthen sustainable and long-term Nordic collaboration and create Nordic discourse around antiracist and intersectional feminist practices in performing arts.

UrbanApa is based in Helsinki and is an anti-racist and feminist art community, that acts as a platform for art events, new ways of doings, and discourses that center on art. UrbanApa’s values include communality, intersectional feminism, decolonialism, inclusivity, equality, softness, play and joy. The community strives to look into the future, to re-think the kind of art, that could and should be done.

HAUT is based in Copenhagen and is a performing arts organization, which focuses on artistic development work and knowledge sharing. Through collaboration with a wide range of art institutions, HAUT creates space for performing artists to develop and immerse themselves in their artistic practice under sustainable working conditions. HAUT and bastard.blog are collaborating in order to find new ways of documenting artistic research and work methods.

The first phase of the project, taking place during 2020 – 2022, consists of an artistic co-production CAMOUFLAGE, a series of workshop labs and a small publication. In this first phase the collaborators are: UrbanApa and Zodiak – center for new dance from Finland, MDT from Sweden, and Haut from Copenhagen.

The first day, we started with an introduction of the two-day seminar given by Sonya Lindfors (she/her), who is the artistic director of UrbanApa, and who spoke of the want and need to create a platform, which deals with intersectional feminism, and its many different possibilities and detours. Lindfors is a Cameroonian – Finnish choreographer and artistic director, who also works with facilitating, community organizing and education. She holds a MA in choreography from the University of the Arts Helsinki.

What stood out for me in the introduction was the gentleness and softness, which laid the ground for the work we all wanted to take part of during the seminar. Lindfors spoke of the emotional labor, which is always a major part of doing transformative work, and she suggested tools as to how one could respond and react within one’s own body, when faced with uncomfortable truths and facts, which perhaps restructures notions and ideas of both oneself and as well of others. Embodying the knowledge as well as letting the body react, needing snacks, silence, care, talking etc. was just as much part of the practice of intersectional feminism as listening to the different talks, which were taking place.

Lindfors was intrigued to investigate through COMPLEX COMPLECITIES, what the local conversations on intersectional feminism are currently about and how they take place, and she emphasized that for her, the title of the seminar had been chosen, as to point towards being complicit rather than being an alley, a term which perhaps has become a bit to mainstream and lacking in meaning.

In her definition, being complicit could point towards being a part of, whereas being an alley can be more passive. The listening and subsequent thinking should ideally move the audience to take part with their body in these questions, while allowing for dense complexity, which has no straightforward answer, and where permanent fixes will not be found.

How to Change Things?

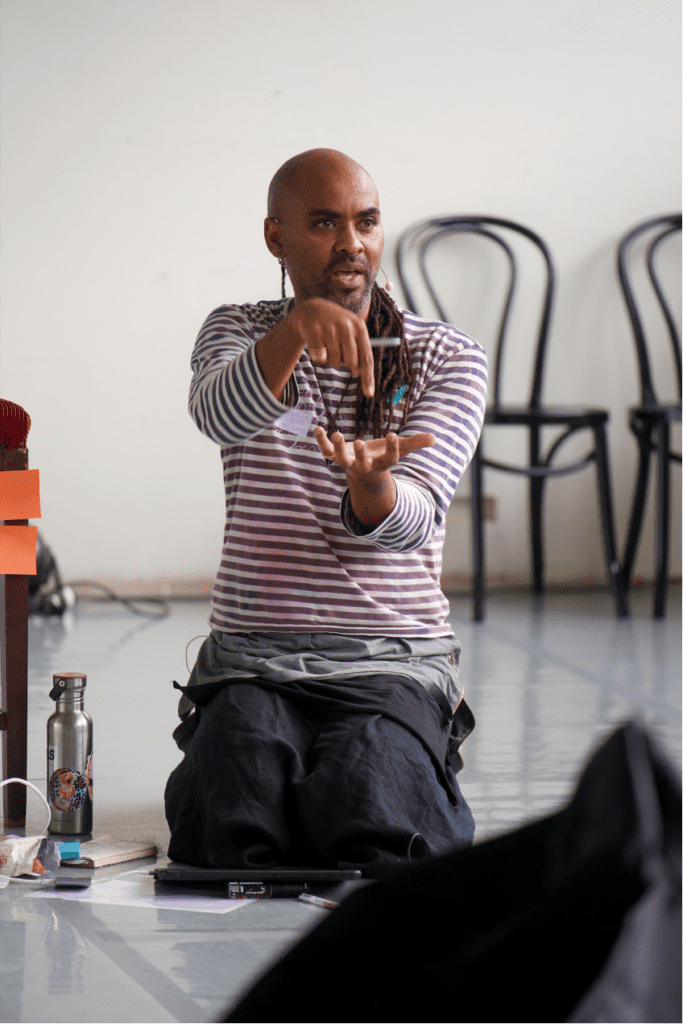

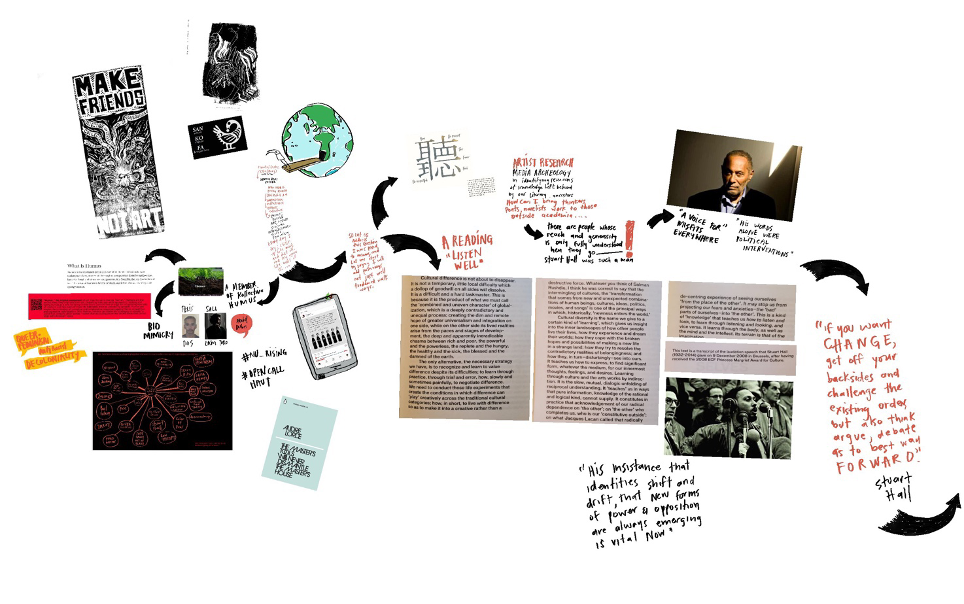

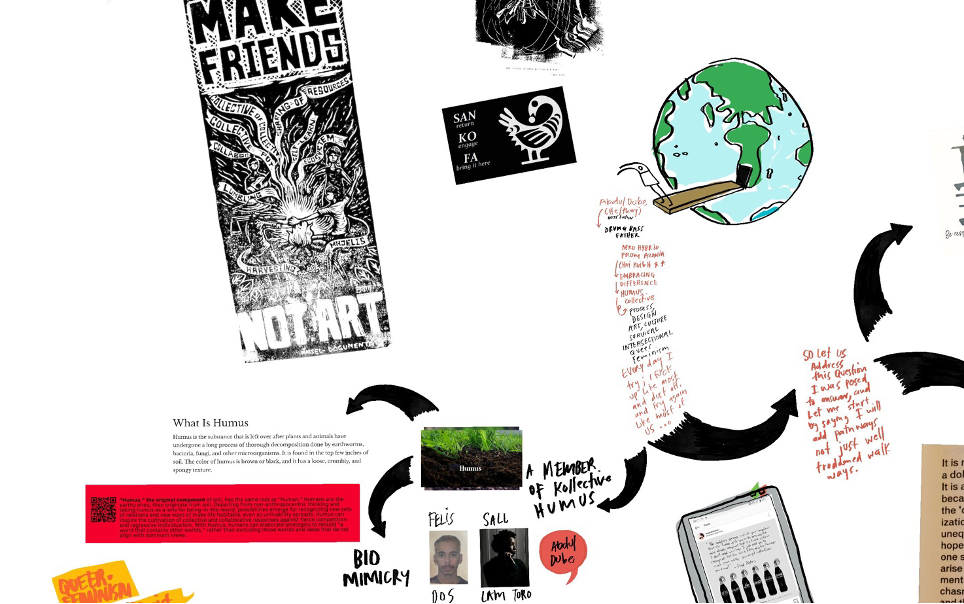

The first talk was by Abdul Dube (he/they), who gave a keynote titled How to Change Things? -in which he beautifully continued the thinking of Lindfors on how listening and thinking are connected. Dube is a multidisciplinary artist, designer, curator, and workshop facilitator.

Dube emphasized the need to reject the pressure, which can easily come with the connotations of being a keynote speaker, and this was symptomatic for his entire thinking: to look closely at the conditions under which we all create, and how to create in a way which is kind, gentle, open, and yet critical.

He pointed out, that when one really listens, which is the position most of us in the room would be engaging in for most part of the seminar, it was an active position, not passive in any way, and something which involves several different points of focus to be at play at once, allowing for the full experience of the narrators perspective: hear, be present, see, focus, feel and be respectful.

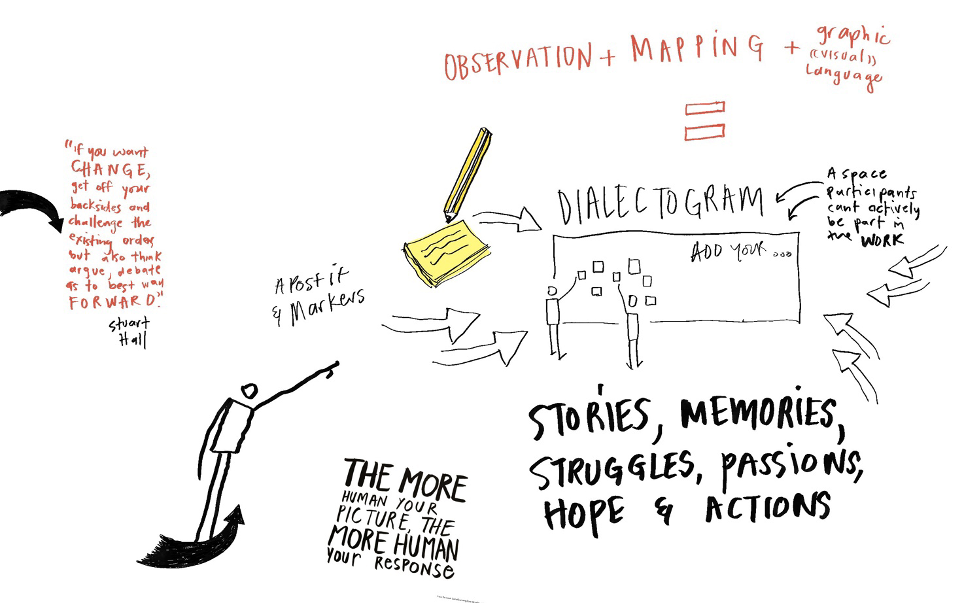

Dube explained their working method, when working for example at Documenta 15: drawing as a visual recorder of what has been said at meetings and seminars, to manifest what had happened and make it into an archive. The visual recorders worked as an expanded mind map, and Dube gave a strong focus on the illustrative side, to make their listening into a form, giving strength and room for what is unfinished and in process. This becomes a way to hold memory, in all its subjectivity.

A question reoccurring in Dube’s talk was:

How can we work with each other?

The question has been especially important, when Dube had taken part in the large-scale structure of Documenta 15, curated by Jakarta-based artists’ collective Ruangrupa, where intersectional feminism had been at the very core of the work. The question evolved into:

How do we work together, staying true to ourselves, while evolving to better understanding and honoring each other’s perspectives and differences?

Dube spoke about how most artist collectives do not focus on the art market and the prospect of selling their art, which allows for an artmaking and thinking, which moves towards a wish, and a statement rather than a question:

Make friends not art.

Dube also spoke of the African word Sankofa, which derives from the Akan tribe in Ghana. The literal translation of the word and symbol is: “It is not taboo to fetch, what is at risk of being left behind”.

The word is derived from the words:

SAN (return)

KO (go)

FA (look, seek and take)

The sankofa symbolizes the Akan people’s quest for knowledge among the Akan, with the implication that the quest is based on critical examination and intelligent and patient investigation.

The symbol is based on a mythical bird with its feet firmly planted forward with its head turned backwards. Thus, the Akans believe the past serves as a guide for planning the future. To the Akans, it is this wisdom in learning from the past which ensures a strong future.

The Akans believe that there must be movement and new learning as time passes. As this forward march proceeds, the knowledge of the past must never be forgotten.

Dube reflected on the ways in which we can look to the past, to proceed into the future. No binaries are needed in this mindset, instead they are inseparable.

Between each session, it either being a talk or panel discussion, there was time set aside to reflect upon what had just been experienced within small groups. Questions from Lindfors was giving as guiding tools, making all the participants engage with each other and bringing own experiences, struggles and understandings into play.

Intersectionality in practice! – navigating the complexity

Tuesdays second collective experience was a panel discussion entitled Intersectionality in practice! – navigating the complexity.

It was facilitated by Malik Grosos (he/him), who is a multidisciplinary artist working with visual arts, performance and acting as well as working for Sydhavn Theatre.

The panel consisted of Oriane Paras (she/they), an artist based in Copenhagen, working with dance and physical performance-installation, and who was invited to this seminar especially as to speak about Dance Cooperative, which they are part of in Copenhagen. Marie Kaae (she/her) is a dancer, teacher and choreographer, and she has a degree in culture/language studies, International Development Studies (RUC) & Sociology from La Sorbonne (Paris). The third panelist was Julienne Doko (she/her), who is a French dance performer, teacher, and choreographer with roots in Central African Republic.

Grosos started off wanting to recognize the room we were in and wanting to recognize, who was there and did this in a practical sense walking around the circle, we were sitting in. One by one each participant introduced themselves in relation to their work, as well as saying our pronouns and what we were hoping to experience from the seminar. What many had in common was a wish to connect with others, who were thinking about intersectional feminism and start building communities, thereby creating structures, where loneliness in these questions and structures could be minimized.

We continued in the same low-key, open-hearted way, and had a round of word scramble/connotations as to, what intersectional feminism means today. Sentences and words filled the space, floated around, each participants contributing giving way to the next ones, Dube was writing them down on post-its, placing them as small poems on the wall, filling the space which potentials:

Paradoxes – We need to pay attention and tribute to the many layers, which the world consists of.

Interchangeable place in the world.

Power / powerless, centered / decentered.

Norms, shape.

Intersectional feminism can also become a norm, that we can utilize.

Community, connections, beauty, parties, friendships, lovers, differences, connections, movement.

Invisibility and blind spots, class, disability.‘

Grosos brought the focus back to the panelist and asked a series of connected questions, which hit the nail on the head:

How do we see diversity in the Danish art platforms? Is diversity being taken seriously or is it merely tokenism, which is at play? And how is this felt both from the inside and the outside?

Kaae told, how she had finally been included into the Danish art scene, but only within the last two years, after a long international career. She emphasized that after the murder of George Floyd, there had been a renewed attention. She pointed out that racism is nothing new, but now we are talking about it in more obvious way.

Kaae explained that in Denmark, but also Paris, which she knows well, there is a lack of representation the closer we get to power. For example, in the case of dance, it’s the choreographer, who claims the right to the be the only one, who is acknowledged, yet many of the dancers, who can have another background than contemporary dance, do not get any credit, which subsequently means a big divide in salary and honor.

She expressed a need to have choreographers, who have a background in, what they are directing – when it comes to expressions, which are not only informed by contemporary dance and European traditions. And when it comes to being hired, there need to be a legitimization of other dance styles, meaning that there need to be a degree program in dance education, which is specialized in rhythmical dances, for both dancers and choreographers. That would legitimize progressing into that direction.

Doko picked up the thread and spoke of, how it had been, when she moved to Denmark. She was already trained in many different styles, and it was important for her to emphasize the aspect of technic and the language, which comes with it: because technic is, what the schools are interested in teaching. It’s not just ballet, which has technic, West African dances has technic as well. Yet she was not taught that, when she was taught about West African dances – because the focus comes from a European tradition. But when working in a context such as Copenhagen, there seem to be no other way offered as to assimilate, what is fetichized.

Grosos handed the word further on to Paras, and wanted to know, how these questions play out in a queer platform such as Dance Cooperation. Paras explained that Dance Coop is a community, which has been much needed in Copenhagen, and where it becomes possible to raise issues, which can be hard to deal with as an individual. This also means it’s a slow process, because many voices have to be heard and considered, but also because all involved needs to sustain themselves through funding, and the time it takes to get this is palpable. The platform has finally gotten some support, which has giving them some more possibilities.

Grosos continued by enquiring into creating platforms, as all the panelists have done in the past, which had happened out of a want but also a need, because institutions had not invited them in. A follow up question then became:

Do we need the institutions and if yes, then in what way?

For Doko it had been a journey, where she was used to manage myself, without money, because she was not getting funding, instead she was funding herself, and then slowly she could build bigger and bigger. Last year Doko finally got some funding, which had made a huge difference. She explained how a vision cannot fully succeed without support: You are a small player until you get money. This changes when you work with institutions and often you get more money. The process has much to do with learning to talk to institutions, and that education comes from schools.

Doko had to learn to write applications to Danish Arts Foundation – and even though she has an MFA in French Literature and translation, it was almost impossible to learn the art lingo, which is required to get funding. It had been a relief for her to find Projektcentret, where she was helped with writing an application.

As a choreographer, you need staff to match your artistic vision: producer, costume designer, sound designer – you need all these people to make a production match your vision – and you need to be able to pay them. Doko highlighted that there need to be a dialogue as to how to talk with the institutions and the institutions need to wake up and understand, how it is to work from the ground up.

Kaae continued and stressed that there is a need for both grassroots movements and institutions, but that especially the institutions need to work with intersectional feminism and more so than in the past. Without institutions it’s impossible to survive as a practitioner.

When it comes to what kind of tools, we need as to implement more intersectionality, Kaae suggested, that there should be more curators, who are not from the same circles and cliques as well as transparency and help as to how to write applications. Institutions could also be better at looking outside the same circle of people, when it comes to degrees from certain schools and offering other ways of applying than merely written applications.

Paras believes a key point is to look at educations – there is only one dance school, which is recognized in Denmark, and they only teach one dance style. Why is it only contemporary dance and ballet, that is recognized here? Paras was educated in France, and they were taught by an Afro-American, and in many different styles: African, hip hop, jazz, contemporary, ballet. In Copenhagen it is about selling yourself, within a certain language, where a lot of history is lacking. There are many limitations as to how your body should move as well as to look a certain way and it’s very violent.

THE CONDITIONS OF DREAMING: CULTURAL POLITICS, SEPARATISM, AND THE ISSUE OF BEING ‘TOO MANY‘

The second day began with a keynote by Cecilie Ullerup Schmidt (she/her), who is a performance artist, curator, theorist and assistant professor at KUA and Anna Meera Gaonkar (she/her), a researcher, editor, journalist and former PhD student from KUA. Together they are working on a postdoc project called ‘Communities of separatism’.

Ullerup started off by emphasizing, that she speaks from an interest and past in performance art as well as artist collectives and collective organizations. Gaonkar on the other hand has become specialized in emotional labor and affects, and especially affects within racialization.

The frame of their research are separatist collectives of racialized artists and cultural workers. One part is to look at the conditions of producing art, within the Nordic region. One of their key questions are:

How is policy being made regarding the Nordic countries within the last 20 years within this field?

Schmidt spoke of the three P’s, when it comes to research within diversity: Program, People and Publikum (audience), which are the three main things to look at, when looking at diversity and who is represented. In their research, they have been especially interested in looking at a fourth P: Policy. The fourth P brings forth yet another, even more in-depth question:

Which kind of discourses and belonging are offered in Nordic cultural policy?

Who can be part of the national ‘we’, that is emphasized through art lingo, as art is often thought of as being for ‘everyone’?

Gaonkar and Schmidt further explained, how despite the overall welfare in the Nordic region, there is a big difference between the countries. What is shared between the countries are a heated debate about identity politics and increase of right-wing parties, and harassment of minoritized and racialized persons.

One of the differences is that the vocabulary is different in each country, and this impacts the politics and funding. In Norway in 2002 they acknowledged, that there were structural racism taking place in cultural policy. Many other examples were given as to how Norway works in a much more progressive way regarding these questions, than in Denmark and Sweden, for example how there are always plural authorships, when working on these topics. The most outrages comparison happens in relation to Denmark, where we since 2001 have seen an increase is disinterest in diversity in cultural policy, and the money used for funding is often earmarked, as we have seen for example with the ‘ghetto act’, in 2018, where art should support gentrification and demolition of social housing projects.

In Denmark Schmidt and Gaonkar cannot find the words ‘racialization’, ‘institutional racism’ and ‘colonial heritage’ in the papers, which are in fact the words used in Norway. Without the words, how do we then address the problems?

The research has recently gathered material by invited seven artist collectives from the Nordic region. They meet in Copenhagen in order to have conversations on, what it means to organize in separatist collectives consisting of racialized or minoritized artists.

The research will continue to investigate the thinking around being ‘too many’, as a way to describe how policy is being many in regard to counting, who gets funding and how those numbers are not representative for the diversity, which is in fact the reality, when we looked across generations, instead the numbers in Denmark are currently being used in a way to up-hold racist and colonial structures.

WHAT´S NEXT? – COMPLICTNESS AND THE POWER OF IMAGINATION

The final panel discussion was facilitated by Kai Merke (they, them), who is a facilitator/organizer both of events and workshops as well as part of their artistic practice.

The panelists where Yong Sun Gullach (she, her), who is a Korean-Danish artist and activist within performance, poetry, film, music, noise and installation art, Vala T. Foltyn (she, they), who is a performance- and installation artist and queer witch, as well as an art researcher and Jupiter Child (she, they), who is a performance- and visual artist from Mozambique.

Merke started the discussion setting an intention, that they have thought of in advance: Hoping and dreaming of ways to fertilize the ground for ways to imagine complicity in the performing arts field.

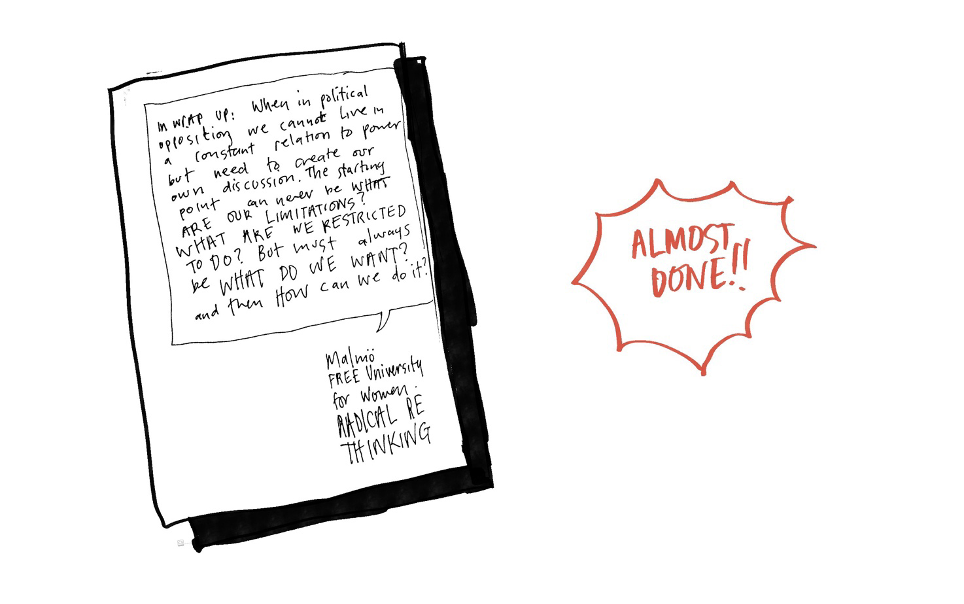

Merke continued by taking up a note up for further consideration from the very first keynote from Dube, which had to do with radical re-thinking:

When in political opposition we cannot live in constant relation to power but need to create our own discussion. The starting point can never be: what are our limitations, what are we restricted to do, but must always be:

What do we want and how can we do it?

How intangible as it might seem, a question, which rises from this line of thinking, could then be:

What kind of dreaming are we doing and how can we dream?

Merke wanted us to stay grounded in the body and therefore they guided us through a body exercise, with inspiration from Resmaa Menakem, which is described in his book My Grandmother’s hands. The exercise dwells within with how the body can cope, understand, and relax into radical change:

deep breaths

let your body relax as much as you want to, let your shoulders relax

take a moment to ground yourself in your own body

notice the outline of your skin and the slight pressure of the air around it

experience the pressure of the ground beneath you

can you sense hope in your body?

where?

how does your body experience that hope?

is it release or is it expansion?

it is tightness or anticipation?

what specific hope accompany these sensations?

is it the change to heal?

to be free of the burden of racialized trauma?

to live a bigger, deeper life?

do you experience any fear in your body?

and if so – where?

how does it manifest?

tightness, painful radiance, tight heart spot?

are you afraid of facing pain that is not a symptom of another pain, but directly facing the pain with its full expression?

are you worried that you would choose the pain, that is the symptom of the roots of your suffering?

do you feel the excitement that herald change?

what picture appears in your mind when you experience that fear?

if your body feels both hopeful and afraid, congratulations, you are just where you need to be for what is coming next.

After the exercise Merke asked the first question to the three panelists:

What does dreaming mean to you in your practices?

Jupiter Child began with speaking of how transparency is becoming more and more visible and how collaborative networks are increasing– and that these things are important to acknowledge and recognize. They see tangible transformation between scholars, institutions and grassroots organizations and artists.

For Jupiter Child dreaming is among other things a possibility to strive for common goals, without presuming that it can only be achieved by a common dream.

They point out, that they are speaking from a black, queer body, who is hyper visible and easily targeted. Religion, gender, sexuality is all part of the matrix as to how one is viewed in society. They dream of giving birth to a multiplex of futures rather than one single future. But to have a dream is also having a privilege. They remind all of us, that Martin Luther King was killed for having a dream – so it can be dangerous to dream.

Telling stories and making art, which concern color and people of color is related to dreaming, and that dream can hopefully reveal more of the humanity rather than just the color – without hoping to exist outside of blackness, which is not the goal.

They continued, calmly stating beautiful, political, and also poetic sentences, such as:

Updating ourselves in pursuit in these dreams.

And then asking:

How can I be part of this, let it unfold?

I dream of a future, where we see past white fragility.

A disease, which cannot be named, cannot be cured.

We need to meet through feeling, through fragility.

When I am othered – how does it feel – especially for white people? Let empathy be more present.

Relatability can be accessed if we allow for our feelings to mature.

I am dreaming of leaving the matrix of art, that is inside the institutions. That we are not co-dependent.

Jupiter Child ends with talking about, how history is filled with feelings, and that it can be hard to convey if you are always in a room with people, who do not acknowledge the subjectivity, which is at play when constructing the narrative of history. Their creativity and art become the healing of the pain, and they do not want to look away from it. They empathize how white fragility is very much based upon the need to look away from pain that happens in othering, and ends by stating that we need to be aware of practices of healing, both individually as well as collectively – one cannot exist without the other.

For Gullach, the notion of dream is not connected to how she thinks about her practice, because as she explained, with dreaming comes painful awakening. Instead, she likes to re-imagine and re-negotiate. In that re-imagining there is a longing to be seen. Without filters, hierarchies, whiteness, meaning finally being seen as a person. And, as she goes on, in that gaze, the same conditions that white people benefit from, would bestow her body. Thereby her body will be forgiving and forgotten – in the same way white bodies can be forgiven and forgotten in the right context.

To re-imagine and re-negotiate would mean to exist without the stress of always being seen in a certain context or with a certain political agenda.

Gullach’s practice is in her own words, about trying to control gaze and space within white supremacy, knowing that her body will be absorbed into the white normative gaze. It is in no way an easy task, instead it is a constant falling-down-movement of trying to control but being controlled.

She further explains that for example the rate of suicide is very high within her community. And this silenced death is something which is fuel for her, as to continue working in art and within a public sphere, and address that kind of narration and lack thereof, giving it language and meaning, so people do not die in isolation and classified only as a diagnosis within the mental health system. When working on these matters, she must forcefully place her work within the context of the Danish art scene. The kind of dying and death, which is always present in Gullach’s work is not welcome, and often hard for a Danish audience to handle.

For Foltyn dreaming is a big part of their practice, and they see this dreaming as a component of witchcraft. They opened their thinking by accentuating, how dreams communicate messages to our minds and our hearts, which we should acknowledge. Dreaming has hopefulness towards the future but dreaming carries weight.

An important question for Foltyn is:

How do we dream the impossible future?

This question is part of queer identity – both a queer future and a queer presence. In that line of thinking, Foltyn reminds us to ask about the past, why are we here, what has happened? What has gone wrong since we must re-imagine the present.

Before moving to Copenhagen, Foltyn lived in Krakow in a house where they had a dream about a bunch of ghosts, coming out a specific place of the house and carrying Foltyn out into the garden. When they woke up, they established an art studio, which related to the dream and the specific space. Dreaming moved into daylight and what many would call reality if one was to make a distinction between dream and reality. Almost seven years later a performance was made in collaboration with three other performers, in a former Nazi ground in Nuremburg. The performance spoke of the history of the house in Krakow, which was filled with a strong female presence of anti-Nazi activities.

Foltyn later in the discussion follow up with thoughts on, what haunts us and how it haunts us?

How are the institutions haunted?

They spoke of the experience of being selected for a residency in Copenhagen, where they were treated with kindness and how this was surprising, as that has not been the experience within the last two educations, they have been enrolled in. To receive help and not being seen as a problem, while doing so, was not the rule but an exception. When a structure offers assistance and help, it opens for a trickle-down effect, where they feel valuable and can better find strength to make new art and research.

The final question from Merke concerned the role of the institutions, and what dreams the panelists would like to envision as to how art institutions could better proceed in the future.

Jupiter Child suggested that people, who are employed at institutions should be sensitive to how the past has shaped the future, and stressed, that nothing new can be created if we ignore the past. We should not repeat the same trauma. Instead, we should strive for authenticity. One way to move forward could be to remember, how important community power is: when individuals come together to form communities, then the institutions need to listen to us – so we need to be strong as a community.

Foltyn spoke of the impossible queer dream, with a reference to Eileen Myles, who re-interpreted Zoe Leonard’s poem I want a President. In the reinterpretation, Myles wrote about wanting a dyke for president and gave voice to minoritized voices and bodies. Foltyn draws a parallel to the current situation within institutions and asked: where are the trans directors? The need for diversity is also lacking in art schools. To see real change, we also need to let people know, that it is time to go as to make room and space for other, more inclusive voices.

For Gullach there is no dream that the institutions will in fact save us because the institutions don’t have the courage to let go of their own structure, which is currently at place.

So how do we become more powerful?

Gullach suggests that we need to build more network, and connect in this sense – we can define ourselves better in this way. We need to let go of the idea of institutions being the best foundation and instead see, that strong networks are a better foundation, and ends the conversation by reminding everybody listening, that we should not lose hope, while holding on to our anger.

Merke ends with a song by Beautiful Chorus, where they invite all in the room to sing along, consisting of two lines, which we repeat, each times repeating the singing along a little louder, more in tune, more as a group:

Please let me be brave

Please let me see my choices clearly