Reportage by Karin Hald from HAUT’s IN CONNECTION, that gives international performing artists the opportunity of a residency at HAUT and gives Danish performing artists the opportunity of a residency with one of HAUT’s international partners. The format is shaped in response to the artist’s and the project’s needs. HAUT and bastard.blog are collaborating in order to find new ways of documenting artistic research and work methods.

SETTING THE FRAME

caterina mora has been in residency at HAUT, where she has worked within her practice and artistic research under a headline entitled ‘On Mother Tongues’, posing questions such as:

What does it mean to be visible in the arts field?

How many years of career do I need to be visible?

Am I visible in the field if I am doing this residency?

How many residencies do I need to be visible?

All these questions spring forth from mora´s artistic research at Uniarts (SKH) in Stockholm, that deals with conflicted trans-Atlantic embodiment. mora comes from a background as a performance artist, researcher, teacher and writer, and she originates from Fiske Menuco (Republic of Argentina) and Rucapillán Volcano (Republic of Chile) and has lived in Balvanera and Almagro (Buenos Aires). She currently lives in Ixelles (Brussels, Belgium) and in Alby Norsborg (Stockholm, Sweden). mora is trained in both academic dance and folkloric dance and her work aims to problematize the modes of production and colonial legacy in representation of Western dance.

ENTANGLEMENT

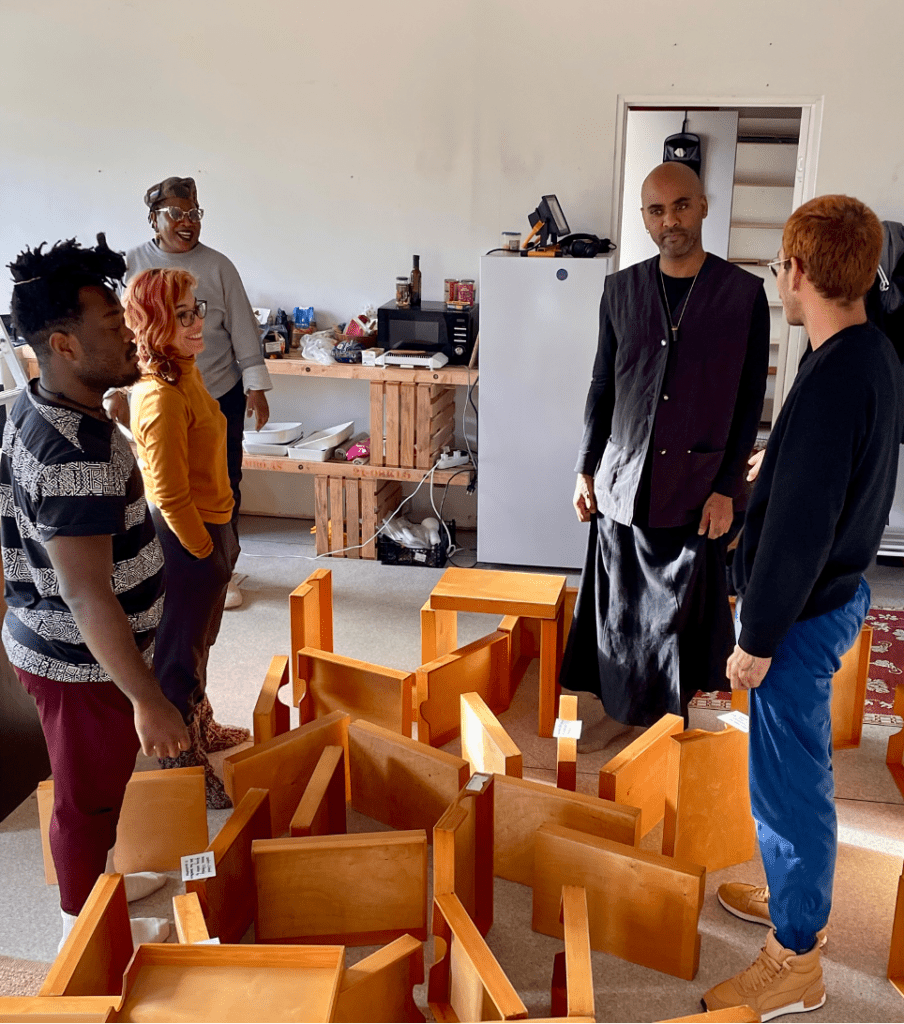

Due to the storm Otto the mini-festival Bevægelse i lille format was shortened into lasting one day instead of two. This also meant that when I entered the space at Teaterøen, a large drawing by Abdul Dube was already in the sun filled space, which showed that a workshop and meeting had occurred before entering as a visitor.

Dube is a multidisciplinary artist, designer, curator and workshop facilitator based in Aarhus, Denmark. His work concerns questions of multicultural belonging, racism and resistance, intersectional solidarity, heritage, sustainability, Black imagination and activism.

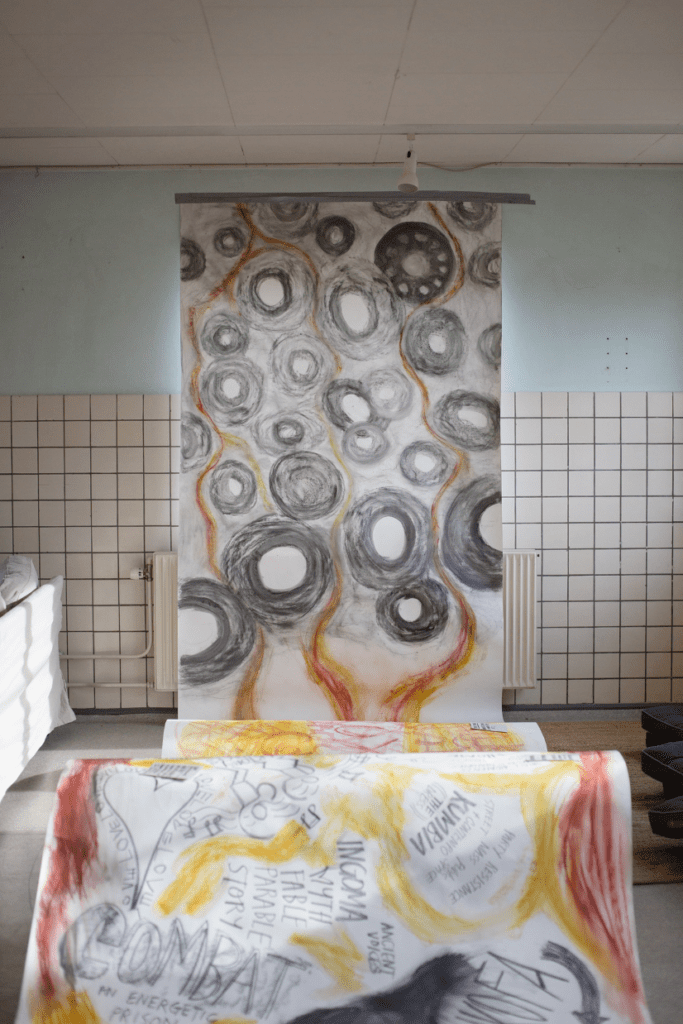

I have in the past be lucky to hear Dube speak and explain their work and working method, when working for example at Documenta 15: drawing as a visual recorder of what has been said at meetings and seminars, to manifest what has happened and make it into an archive. The visual recorders worked as an expanded mind map, and Dube gives a strong focus on the illustrative side, to make their listening into a form, giving strength and room for that which is unfinished and in process. This becomes a way to hold memory, in all its subjectivity.

The same seemed to have happened at the space, where a large-scale roll of paper was fastened to the wall and rolled out onto the floor, filled with both drawings, words, sentences and quotes, as well as a QR code which when scanned took me to a playlist. The drawing served as a mapping of movements, an emotional archive, where entanglements between the different people at the space was held without hierarchies.

THE JOURNEY

The first performance of the day was by Barly Tshibanda, who is born and raised in Kinshasa, Congo. He started to dance Ndomnbolo and breakdance at an early age and received his education from the Academie des Beaux-Arts Kinshasa and INA (Institut National des Arts de Kinshasa) and is currently studying at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Denmark. His practice is centered around decolonization processes and anti-border regime strategies and his inspiration comes from different lived experiences with the European border regime and racism in Denmark. He has a strong connection with local activist and artist groups in Denmark and Congo.

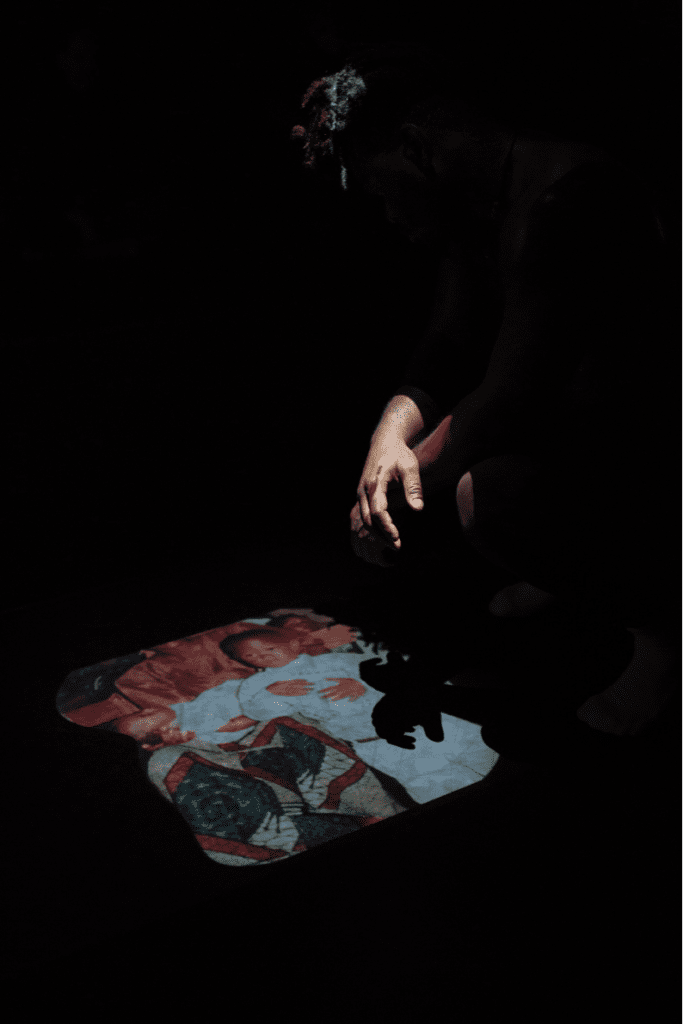

Tshibanda has himself presented the piece as working with the experience of being an asylum seeker in Sweden and Denmark and how it was physically and mentally hard. The performance was an attempt at trying out different tools of healing and investigate how to heal from within a body which movements has been colonized?

The journey was shown in a black box setting, where Tshibanda was first laying on the floor in darkness. After the audience had entered and sat down, he moved into a spotlight, coming from a projector hanging from the ceiling, casting its light as a column down upon the body of Tshibanda. The light changed throughout the performance as to not only be the white light from the projector, but also show different images, which I was told afterwards was images from his childhood. The complex choreography moved in-between three different modalities: Tshibanda´s movements and dance, the images from the projector and a soundscape of a conversation, which sounded like it was Tshibanda and mora talking about love. All three ‘aspects intertwined, and moved in and out of a being clear, visible, or understandable to me. I tried to listen intensely to the conversation about love, but it felt as if the purpose wasn´t for me to grasp it entirely, instead fragments of conversation floated into the space, such as:

Neo-colonialism is still visible…

You mentioned that in Congo, you are not used to saying, “I love you”?

I mean… Words have meaning, but what about action?

But why is it different?

I guess because we are expressing love…

Here Tshibanda started to move, and his motions was louder than the sound, making me shift 0my attention mainly to him, leaving me without an answer as to what the difference between the action and notion of love is in Congo vs Denmark.

The movements oscillated between stretching exercises, to breakdance, into relaxation: different modalities of being a body, from different places and spaces, intertwined in one body, which tried to encompass both a past and present, in hybridity.

IN THE NAME OF ANOTHER BASTARD-CHEAP-LECTURE-PERFORMANCE (RATHER BASTARD THAM CHEAP)

In advance to the minifestival, I meet with mora, where she gave a generous interview, sharing some of her thoughts on coming from a migration process and how she wants to work critically with migration from south to north. We meet in the dance studio at Teaterøen, where we placed yoga mats on the floor, and sat down with warm tea and cake, talking while continuously shifting position, almost as a reminder of staying within the constant flux of the body.

Mora started by emphasizing a key part to making this workshop, festival and PhD in artistic research at Uniarts: the aspect of money and being paid. Because mora is already being paid by the university, where she is employed, she has chosen to use the money from HAUT to pay the other performers that she has invited. Instead of hiding the facts of precarity, which is a struggle that often hits migrant performers more severely than those who have a long-standing local network, mora insists on working towards better conditions, and the only way for performers to become better paid is for us all to speak out clearly about it.

In relation to this, a major part of the thinking and research is visibility and who gets to be acknowledged and show work: therefore, all who are invited have a migration background from the global south to the global north but are locally based.

The PhD, which started in 2021, is about conflicted embodiment and the idea of a migrant dancer, who by changing the context of the embodied practice also hacks questions regarding coloniality. An example could be that it´s not the same if a dancer does ballet in Scandinavia as when the same dancer does it in Argentina, the same goes for tango, or reggaeton or salsa: the values of cultures have different ideas of legitimation, who and why gets to embody certain kind of dances and why?

I asked her what gestures and ideas are within the title Mother Tongues, and if she is working with this notion primarily in dance? Or also as written and spoken language?

mora explained that she is investigating what mother tongues do in relation to a performer. She is looking into how language is made visible and what happens when it is translated, and she is continuously asking herself what in that process is then made visible and what is lost. Something might be lost in translation, yet not merely as failure in a negative sense but also with the potential of hacking and resistance.

mora poured me some more warm tea, shifted her position on the floor, constantly being present within her body, and said:

“I’m interested in looking into the dancing body, in terms of politics, in terms of the speaking body of the dancer; what does it say and what power structures does that body have in relation to the territory of dance and dancing? But also, the art marked that is surrounding that body. I investigate the discourses around contemporary dance and what we perceive as contemporary dance, which has to do with a specific use of time, space, audience and economy.

I think in relation to colonial theory, but I am very critical of the notion of coloniality, because colonial modernity has been situated within a certain group of thinkers where I come from in Latin America. But the term has been appropriated and is now serving to a lot of causes, and that is great, but there is also a big risk about the terming itself. An important thinker to me is Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, who speaks of power within the studies, and that even the theorist who criticized colonial modernity were replicating a toxic power structure, in terms of who are criticizing what.”

Some days later mora performed IN THE NAME OF ANOTHER BASTARD-CHEAP-LECTURE-PERFORMANCE (RATHER BASTARD THAM CHEAP), in which mora made a chorography that showed different styles of dances, which she translated as to show movement from south to north and vice versa.

Another part of the choreography was a script that mora narrated as well as translated, as it was writing in English, then translated into Spanish, all the while the English was being shown to the audience as subtitles on the wall.

The choreography was made in a way that meant that it was impossible to look at mora speaking as well as read the story in English, making me move my head back and forth as watching a tennis match, where the ball is being shot from one side to the other.

The performance moved in-between different modalities and characters. mora tells the story of a young girl called Marie, who is a ballet dancer, and who is featured in paintings by Edgar Degas. mora poses as the girl in the painting, and becomes the work briefly, and gives a contemporary voice and presence to someone who in the past has been silenced. When mora told the story of Marie, she did so in French.

In Spanish mora narrates the story of someone who might be herself or a part of herself. The persona speaks of moving to Brussels and becomes a live model, thereby working with the body within a certain kind of tradition, which calls for certain kind of poses and restrictions.

There are many intricates plays and changes throughout the performance, sometimes she used a microphone as to enhance her voice, or give a certain pathos to the words, at other times the subtitles are missing, which left us who don´t speak Spanish or French to interpretate her words and perhaps looking even more intensely at the gestures shown.

She ends the performance by dancing the Argentinian folk dance Milonga and shows how small adjustments turns it into ballet, thereby conveying the alterations that happens when a body moves in the global south contra the global north.

UNRAVELLING: WH0ES LABOUR IS IT?

The third performance of the day was by Jupiter Child, who was born in Mozambique, and now has their base in Copenhagen. They are a performer and visual artist and draws inspiration from black history via their Makonde ancestry and the black arts movement by combining theatre, dance, song/spoken word, creative writing and storytelling. Their thematic concerns are liberation practices and collaboration continuity.

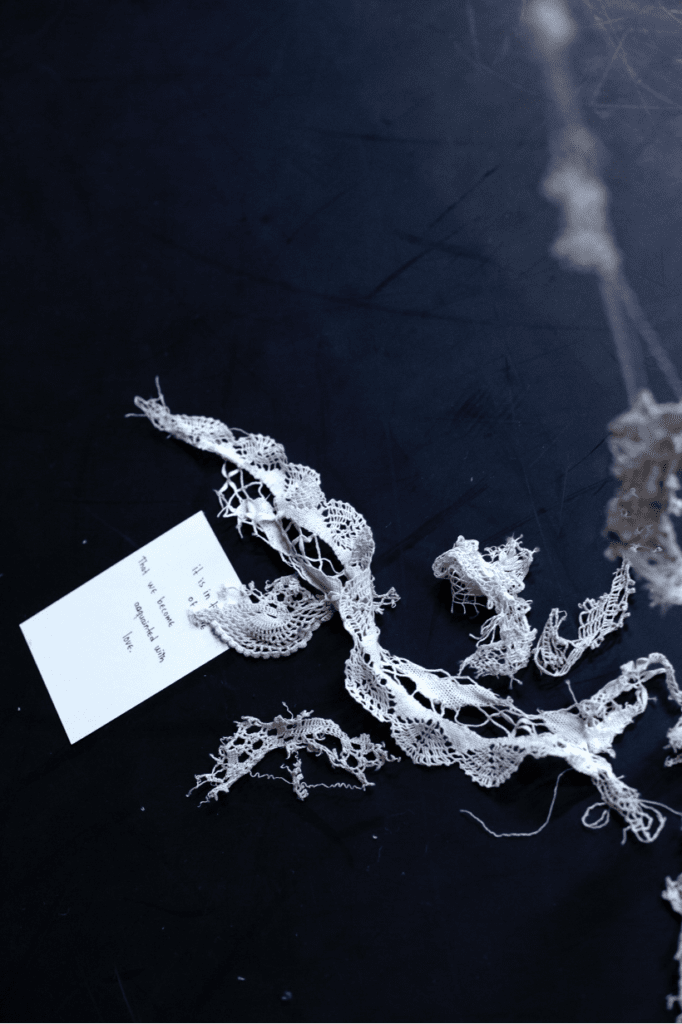

The performance Unravelling: Whoes labour is it? was seeking to hack, deconstruct and dismantled a colonized tongue. A theatrical setting was set in place when entering the black box, which was fully lit. Jupiter Child was sitting in the middle of the room on a chair, dressed in a long white dress. Beforehand we had been giving a piece of paper with instructions as to how engage with the participatory performance:

“You´re about to enter a utopian deconstruction site & landscape.

The zeal to unlearn what we have been taught must be collective, inclusive, and not exclusive to a few.

Unravel calls on everyone to engage in the work of liberation, activating a collective work force in deconstructing, unravelling, dismantling, monolithic structures stitched into the fabric of colonial legacies.

- Join the team and be collaborative.

- You must actively engage in the work of deconstruction.

- You are not a spectator; you are a worker.

Grab your tool of choice and get to work.

- You must apply both physical and mental labour.

- Time consciousness and discipline must be observed. Keep in mind you are a shift worker, and you must change station at the sound of the bell alarm.”

In a circle around Jupiter Child´s chair were vintage crochet coasters and larger, more dense crochet blankets hung around the room. On the floor were small pieces of paper, which for example said:

“The artist is not alone in a black box.

The artist is framed by some darkness of speculations

Interpretations

constructions

biased opinions

prepositions of anonymous

Madness”

Jupiter Child was already at work, unravelling a large sweater, working with intensity and concentration, when we all entered the room. With the instructions in the back of our minds, everyone found their own piece of knitted fabric to dismantle. It was a surprisingly difficult work when I started to tear into the wool – at first it felt like I was doing something bad, destroying something with was made with a meticulous hand. But there was no way around it if I wanted to participate and be a worker in this room and performance. I had to start using strength and urgency, to be able to pull threads of the past into deconstruction.

At first everyone involved was quiet and behaved in a polite manner, but Jupiter Child showed us with different gestures that it wasn’t necessary – instead this destruction could happen with a sense of joy and ease, as well as engaging with each other. People started to help each other, lending scissors which Jupiter Child slided over when the knitting was too tight for fingers to handle, gave instructions and sometimes banged a metal pan, making everyone shift positions. The joyfulness increased and finally Jupiter Child, with a laughter that filled the whole space, proclaimed that they were tired of working, took the hand of a friend, and left the space.

COREOQUE?

The third performance was by Felis Dos, who was born and raised in the countryside of Brazil, surrounded by faith, class troubles and spirituality. His works intents to raise destruction, uncertainty, and discomfort. In painting Dos has found a place to focus and create the images and universes he feels needed in the world, but his practice touches and expands itself through other media such as photography, video and performance.

Coreogue? had two distinct modalities; first everyone laid down on pillows in the black box and soundscape, which lasted for roughly 25 minutes, was played. The atmosphere was relaxed and pleasant, gentle and opening. Dos encouraged us all to think about movement, in our body or how we moved around in our daily life, and that we could take the presence into the situation of laying still and listening.

The soundscape itself was first a form of talking, which in fading sounded more and more like a broken radio, then it drifted on to music that had a childlike, playful feeling to it. Slowly drums and other electronic sounds were added, making up a rhythmical landscape, which made me drift off into a calm uncertainty.

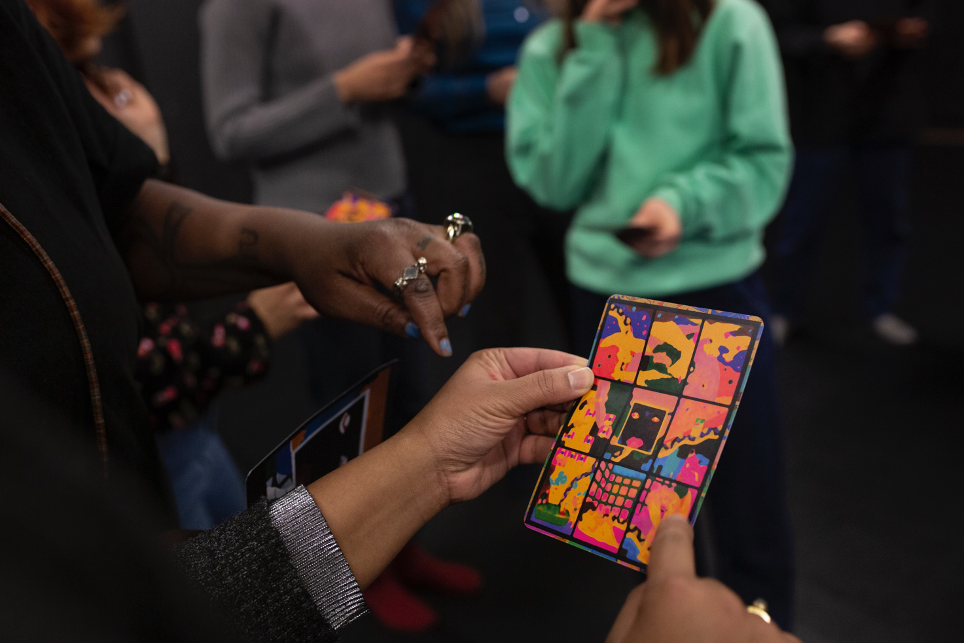

The second half of the performance was structured as if everyone in the room was a dance company, creating a choreography for a show. The way it happened, was by each participant picking up a card which laid on the floor, each having a word and an image on the backside, which was part of a whole, which could be seen on the other side.

First, we started walking around, focusing on the word which was written in Portuguese. Each word on the cards was a word for something in Portuguese, which cannot be translated into English. Dos asked us to tap into the consciousness of that which we cannot translate or do not understand, and then to think of that in relation to movement.

Dos spoke of the experience of not being understood when he spoke Danish, because his Danish is spoken with a thick Portuguese accent, but also because the people didn’t use their eyes to see what he was saying, they only listen.

We walked around amongst each other, started to activate the body which this consciousness between body and spoken language. Then the cards were turned around, and a process of comparing cards with others and seeing how the connect as the larger image began.

The final assignment was to translate our own image into a movement, which happened while we were moving sideways in a circle. Any person could start presenting a movement, which was their personal interpretation, and which was then carried on until another person started making a new movement.

CONVERSATION WITH MARY TESFAY

The final part of the day was a conversation between caterina mora and Mary Tesfay.

Tesfay is an educational anthropologist with a BA in social education. An old hip-hop dancer that found interest in theater 20 years ago because of a dance theater project based on her personal stories about being young and black. She works as project manager at C:NTACT, which is an organization that works with social/cultural education through art and storytelling. She is also a 4Xboardmember within theater and social organizations – because, as she says: representation matter.

The questions which mora and Tesfay set out to negotiate and debate was how to promote infrastructures, to make the (in)visible visible – and how to make it sustainable? The talk overall sought to address questions about representation and visibility in the crossfield of art and education, as well as bring reflections on the Nordic performing arts production and critical ways of generating and challenging institutional policies in the local context of Copenhagen.

Tesfay starts out be explaining that normally when people ask her how long she’s been doing this kind of work, she says 5 years, as that is how long she has been working at C:NTACT. However, she has recently realized that she has been within the arts field for 20 years, because she started making theater already back then, as well as being in panels and talks. Interestingly enough Tesfay didn’t see that as being part of the art fields, as she disregarded this kind of work as part of an (artistic) practice.

mora asked Tesfay to reflect upon what she has experienced at the mini festival as well as posing the question:

How do you translate and transcend something to make it visible?

Tesfay: “I think a lot about making the invisible visible through my work, with primarily young people, but also just in my private life; me as person, me as a mother, me as a black woman in Denmark. How to make my perspective visible? For me, I cannot separate who I am and what I do and how I do it. But the thing is, that quite often we are not framed to understand what it is that people bring to the table. I have a hypersensitivity towards that, because its so important. And that´s where can make something special, because through art we can communicate, we can make different ideas and experiences of life visible and amplify it. But I recently realized that there is a huge difference between amplifying something and making it into a sustainable change.

And that is where my 20 years of actually being within the arts fields comes in – I have in fact been creative for a long time, but because we don’t for example see rap as being creative, I didn’t think of myself in that way.”

Tesfay continued on as to touch upon her background and her deep passion to bring culture to kids:

“I have a background as a refugee and I am part of a demographic group that is called “foreigners”, or so called “new-danes”. It’s often framed as if we as a group don’t have a lot of access to art and artistic citizenship, but we do, if we see that start to see that what we do, is in fact also art, but it was never framed to be that, by neither us or others.

The theater that I was part of 20 years ago was called “Trespassing”. It was a theater where we change the discourse from “we hear so much about them, let’s hear from them instead”. Because it was framed as a social project, it wasn’t understood or seen as art”

When asked further into this, Tesfay explained how the perception differentiates from the “outside” to the “inside” of these kinds of art projects:

“It comes of a as one way channel of distributing resources and stories, without taking into consideration of what we are bringing to others. In this idea of “them” as “us”, there isn’t much understanding of the fact of what “the others” actually bring to the table.”

Fast forwarded 20 years, to now, Tefay just had a project at C:NTACT, entitled “My meeting with limitations”, where 5 young people age 14-17 and from Nørrebro could speak on what they themselves experience as limitations. The same stories that they had to share, was the same stories that she told when she was their age. And Tesfay emphasizes think that that is worth sinking in – 20 years is a long time, and still people are asked to share these stories, but without them leading to sustainable change.

Tesfay looks around, and says calmly:

“We need to change how we perceive each other and yourselves.

For me it was expected that they would talk about racism, discrimination, but what was surprising was that none of these youths call themselves Danes. They would call each other “strangers” or “foreigners”, anything but Danish.

At these talks with C:NTACT, there is always engagement with the audience. We always have a Q&A – because it’s not like going to the zoo, the audience need to engage and not just ask to be told these stories. All the brown kids share the experience of the those on the stage, but all the white kids and teachers would not have the language to include themselves in the conversation in a good way. They were afraid of saying something wrong but did it anyway.

My job is to facilitate this kind of dialogue, and I can’t remember the last time I had to be so hard at work. Because I had to think about the questions the audience asked, how to reframe it to include them as part of including them into a part of a bigger Danish narrative and how can I take what they are answering and translate it into something that the white kids and teachers will understand as a bigger “we”. I was heartbroken by this because the dialogue I have been part of for 20 years has not sipped down into youth. There is a huge gap there.

I think we should all reflect on that.

I believe that most people who communicate and express do so because they have something to tell. But is enough to have that urge? To tell their own worldview and desires… But if it doesn’t have any real change other than “oh I was touch by this work” – but then you go back to your safe life and world, then what does it matter?

At least that is my take on it.”

mora picked up the thread and spoke about making the visible visible:

“Last week, when we were in the workshop together, we didn’t have to explain yourselves to each other, because we were all migrants, we could share other things, such as: “how can we expose yourselves – how do I do it, and taking into this specific context?”

That in turn brought up a question as well as a subsequent refelction for mora:

“Who is my audience and how do I mediate?

It is a lot of effort to create a “we”, and at the same time it´s ambivalent: because it´s also: how do I create conditions for others?

Because right now I have a salary and a fee, I can create a platform for others, because my fee for this kind of residency I can distribute to other artists.

But it´s always about: How do I make it sustainable?”

mora asked Tesfay to speak specifically about becoming a board member and doing board work:

“I think board work is really boring, and it’s pretty new to me. But by being present in an all-white-board, I am bringing something new, with has value to all the conversations that they don’t really have, just by me being there. By taking up space something new can happen. And it can be anyone who doesn’t fit the standard fit for a board member.

“Brun og Dansk” – which was a blog I made – I wondered about why I was doing that work for free? And in that respect also: What are people using my blog for, where does that knowledge go – so I stopped writing. Because now, it’s important that I take space, but also that I engage in a way where I can see that people will reflect on the same matter as me, as well as being paid.

I want dialogue.

mora rounded of the day with some final questions for Tesfay:

“How to deal with vocabulary when dealing with these kinds of topics? Such topics as racism, discrimination, representation, as they are full of symbolic value, is it about dismantling or creating new vocabulary? Which has to do with the status of visibility.”

You refuse to use the word of inclusive – I know that from previous conversations we had – but what does that mean to you?”

Tesfay: “I really hate the word “inclusive” because who is being included and in what? Who has the power to define who and what is let in and for me including is often about just giving a little space, then we can tick of the “brown person box” or “queer person box”, and it takes away from understanding and viewing whatever you are trying to include as something wholesome in itself. Its uneven when we talk about “including”. The ones who are trying to include never understand themselves, in their own privilege and blind spots.

I want to be leveled.

And it’s important to speak about. When someone says they want to be inclusive, ask them: what do you actually mean? Remember to ask questions – sometimes that enough. People who do it, don’t necessarily want to be harmful or racist, but merely formulate themselves like that because they are uninformed and has never been asked to take a look at themselves.

And in my experience, people want to change, if you open this conversation up.”