The performance art school CURRICULUM arranged a lecture by German dancer and choreographer Joana Tischkau at Toaster in Copenhagen. bastard’s editor, Mette Garfield, has now talked to her about her work with the performative institution The German Museum of Black Music and Entertainment, which rewrites German history of culture.

When we first meet on zoom it quickly turns out dancer and choreographer and co founder of The German Museum of Black Music and Entertainment, Joana Tischkau, like me love cats. She smiles and laughs, when she sees my cats jumping around in my apartment in the background. It’s difficult not to smile and laugh along with her, and then she returns to our otherwise serious and pleasant conversation, which primarily touches upon her important work with The German Museum of Black Music and Entertainment, a performative institution, which rewrites German history of culture. She initially says about The German Museum of Black Music and Entertainment:

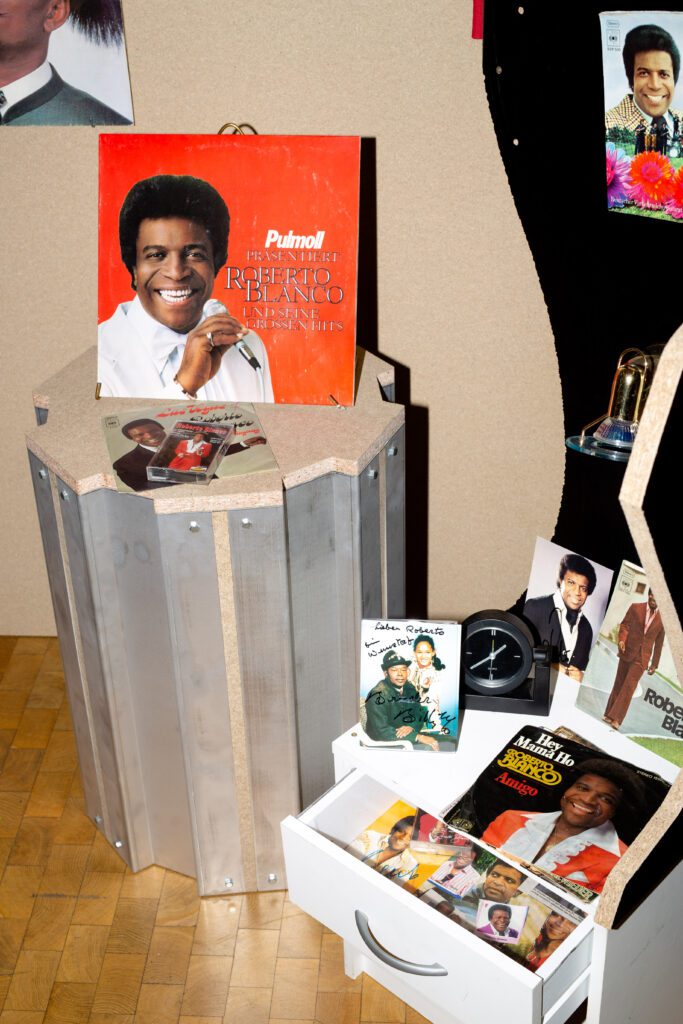

Joana Tischkau [JT]: On one hand it’s a real collection, an archive, a collection of mainly records or media that stores music. We have a lot of cd’s, cassette tapes, but we also have all other materials, that is connected to music and entertainment, which is posters and flyers, we even have old concert tickets. We also have some original costumes by performers and also gimmicks, e.g. a stuffed dog, which plays a song, when you press the hand. The song is also on a record in the archive. So we also have fan material. That’s all physically there.

But then there is also of course the semi fictitious idea, that we are a museum. Publicly we are an institution, as if we have our own house, where the collection and material are exhibited. We have a website and an Instagram channel, all the social media, that communicates the institution. And my email signature would e.g. say, that I’m the director of the museum. Then there is of course also the aspect, that we also create and curate events. Recently we were invited to talk at a jazz symposium in Frankfurt. There we appear as experts in black, German music and entertainment. And our financial infrastructure of the museum is as a group of independent artists working together.

Mette Garfield [MG]: So you are a self-institutionalized organization, and you have taken over museums in Germany, right?

JT: Yes, we took over the Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Franfurt, and we also took over a theater in Berlin, but it was a digitalized program because of corona for a week. Hopefully we will take over a museum in Schwitzerland. Whenever people contact us, we say, that we can install the museum, but what is really necessary is, that we can completely override the museum, which is already there, in a way, that you think there is a new museum in town.

MG: How have you collected the material for the museum?

JT: It was really hard work. We partly bought it e.g. on ebay, and we have a regionally ebay, we bought stuff from people’s homes. We also did calls, made flyers to institutions to spread it, and say: ‘hey you can donate material for the museum’. We also went on flea markets and to records stores to buy records. There is one important institution in Germany called ‘Each on one teach one’. It’s a black community organization in Berlin, and they have actually an archive already and a small library with material from black German activists from the 1940’s and onwards. Black German activists, who worked and collected material and published for magazines. What ever they did, and whenever someone died, they donated their material for this archive. We went there and copied a lot of the stuff they had.

MG: At the lecture at Toaster in Copenhagen you explained how you went on a research trip to the US, would you please tell about this trip?

JT: We first spent time at a residency in a small town in Germany. We just spent time with all of our heroes from, when we grew up. We thought about, how their careers had developed, and where they were today. Then we had the opportunity to go to Detroit. We went to Motown Museum, which document the history of Motown. The label distributed the records of Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder and Michael Jackson, really important figures in African American music industry. And the museum is completely independent, because there is very little state funding in the US. We realized how it operates very different. It’s really commercial and works in a similar way as e.g. Madame Tussauds. But nonetheless it tells the history of Motown and the making of these songs.

We also visited the Museum of African American History, which also documents the black American history in quite a painful way. It really recreates the travels of West African slaves to the US. They have these wax figures too, like Madame Tussauds. We realized, what a museum also could be. The Museum of African American History was made like a whole experience, and like you should be entertained and affected. It was totally different from a rational cognitive experience, where you try to work out, what the art tries to tell you and the work is being analytically brought to you. This fitted very well with the biographies of black artists in Germany, that we had already researched. You have black singers singing German folk songs, superficial funny, never serious songs about love and romance, but at the same time you have black artists singing songs, which you don’t associate with them, what it does to you is really interesting for us. We wanted to take that with us, that you are being emerged back to a certain time.

MG: So how do you display the material in The German Museum of Black Music and Entertainment?

JT: We build our own exhibition an architectural structure. We display the material very chaotic, not in this white cube clean way. There is no explanation tags or anything. You walk in, and you are smashed in with this material. These images and posters and you also hear music. And then a guide tells you about the stories of black entertainment and artists, how they are connected and not connected. And you are being guided through the whole thing, so you are not being by yourself during the 20-30 minutes. You are constantly bombarded with information and material. We really wanted it to be an overwhelming experience. As a black audience member you enter a space, where you see exclusively black artist, and for a German audience member it is very unusual, and off course for a white audience member too. ‘I didn’t know, I know so many black artists’. To make visible there is a whole black history of artists, who have lived and worked in Germany, in the 1940’s, 50’s, 60’s, some very famous and some not so famous.

MG: This format is a way of deconstructing the museum, the white cube. Could you maybe elaborate on how and why?

We adapt the cultural technique of the museum, but actually we are not saying, regarding preserving and archiving of black history, that this format is actually the ideal one. We have huge discussions of restitution of colonial arte facts, at e.g. ethnographic museums, there is this whole debate about it. One of the claims and arguments from the community, that want their arte facts back, e.g. some of the Benin bronze statues are not meant to be static in a space. They are cultural goods and arte facts that have to sit in a living space. I read in an article, that some arte facts are not meant to face in a certain direction. When you live with them, they have a certain purpose, maybe they are supposed to be touched, to be treated a certain way, and all of this cannot happen in artificial museum spaces.

One thing is the question of, what arte fact do we preserve, and how do we preserve them? What does it mean, when we take them out of their sociological context? But the material we collected is so mundane. It is records and cd’s, stuff that’s been produced a million times, everyone has them. That also in a way is disrupting the logic of the museum. ‘I have this record myself, so why is it in a museum?’ That’s what we want people to think about. What stuff is worth collectable, and what stiff is preservable? If I got it on ebay for one dollar, what is its value?

The fact that the museum is semi fictitious and not a real house is also about this. We are not sure if a real house is the right thing. The idea is to further develop the museum, maybe it’s a space or maybe is more a space of oral history. That’s also why the guides in the museum now, tell the story from their perspective. It’s also failing. One guy tells it this way and another will tell it another way. They will mix up dates and stories about the material. That also interesting, what does it mean to construct history as a museum?

MG: When you take over a museum, what do think about, how the museum might use it as black washing? What are you thoughts about that?

It’s a difficult question. We can try to be careful. I think it is the same issue in many fields now. Even when I make my work as a choreographer, where I get invited, because they want a position of color in their program.

I’m really torn in this. I heard in a commentary that veganism is now a trend. A lot of people are vegans. Some say it’s a trend, it will go away, but actually I think some trends will actually change things. Maybe people are vegans, and it’s a fact, that people will not eat meat and consume animal products anymore. It’s a trend adopted of capitalistic order, the same with diversity, which is also a trend. I don’t know, but I do believe it confronts people with the whiteness of the institutions. Their working fields and suddenly you are confronted with this material. And in Germany a lot of the material is being frowned upon. There a lot of ‘trash’, euro dance, schlager, folk music, all of these music genres are not part of the high culture canon in Germany. We try to shift this canon.

MG: And what have you discovered by collecting this material? I know you have made analyzes regarding attraction, sexualization and affect in black pop culture?

This was my starting point for my early work. I was then interested in how the black female body is perceived on the European stage, not just the German stage, and in general in European visual media. I was busy analyzing that, and this led me to bigger questions about how black bodies are perceived in general on stages, how can they even appear? I worked together with Anta Helena Recke, and she copied a very famous classic play and casted all characters with black artists. The piece was exactly the same, the set design, costumes etc., it was just the actors, who were black. It was a big scandal, because the critique was, if you make this theater with refugees, it will not be better. But the actors were not refugees. They were professionals. The critiques really took on to it and wrote; the piece is boring, we didn’t see the color, why is she doing this, it doesn’t matter? But it really showed that of course, there is an issue at the German theater scene.

Anta Helena Recke and I, we got interested in each other’s work. I got interested in appropriation. I was interested in, what you can do on the other side, if we of color appropriate white institutions or goods? It all came to the basic of what can a black body represent on the European stage? We will be understood as refugees, if it’s a woman she will be sexualized, maybe she’s a prostitute, these things. It also came together with how we as black Germans are influenced by black American culture. What does it mean for black Germans growing up with these images of American black culture. These questions are still with me making work, who do I work with, how do I use bodies of color? It was also a liberating thing for me to remove my self. If I can only perform my blackness on stage, I would rather not do it.

MG: Yes, you also work as a dancer and choreographer, will you tell about that please, and how is it connected with your work with The German Museum of Black Music and Entertainment?

I always danced as child. I think it’s connected to it, because growing up as a black person in Germany, you try to find your space, and the only area, where your saw yourself represented back in the nineties, was in TV in entertainment industry. It’s still like this in the US. The most famous black people, we know, are entertainers. Black people have always been represented in the entertainment industry. I also saw myself like that and studied dance, when I was a bit older. Then of course when you enter the high end of art institutions, you are confronted with the white canon of dance. All the choreographers you learn about are white men or women. I was also confronted with the practices I have learned from hip hop, house, commercial dance, don’t have a space in western contemporary dance, it’s also very limited, what can happen there. That’s how I started to question these connections. How can my body even exist in this space of western contemporary dance culture? I began to think, about why and how black dancers were kept in the entertainment industry and cannot be a black German avant garde performer. They were kept out. That’s why I began to think about, who are our idols, the people we can look up to in the canon. I realized most of them were entertainers. There are of course fine artist but they are not known.

MG: What are the plans for the museum in the future, what are your dreams for the museum?

Ideally we want a museum. We are critical about it, but we want a house or a space, to first of all our archive. That would be very important. We don’t even need to run it, but for sure it would be important to have a space, which administered the history of black German culture, not just pop culture, but also in general. There are small unions, which do that, but it’s very small and on the periphery. And of course it would be great, if it was an institution as big as Deutsche Museum in Berlin or Historic Museum Frankfurt. That would be our goal.